In 1963, Andy Warhol opened his first Factory in an old firehouse on East 87th Street. In 24 years until the artist’s death, the Factory occupied four different locations in Manhattan. Warhol wanted the Factory to be a place of artistic creation, a sort of workshop where he could experiment with painting, printing, photography, and filmmaking. He wanted it to become an art factory. Indeed, Warhol also turned the Factory into a trendy social hangout spot, welcoming everyone who wanted to enter his universe and find their fifteen minutes of fame. Andy Warhol’s Factory redefined concepts of art, fame, and popularity of the time.

Who Was Andy Warhol?

Born in Pittsburgh on August 6th, 1928, Andrew Warhola was the son of Czech immigrants. He grew up in a poor family, marked by the polluted environment of the suburbs he lived in and the deprivations of the Great Depression. The Byzantine Christian iconography that populated his childhood home left a strong impression on him. After high school, he studied at the Carnegie Institute of Technology before moving to New York. This is where the real Andy Warhol was born.

As the golden age of Abstract Expressionism came to an end in the late 1950s, a change started taking place in the art world. The daily life and behaviors of an entire generation, deeply marked by a fundamentally capitalist cultural society, started being expressed through television, advertising, comic books, and fast food. American culture was at the height of its influence. As a reaction to this, Pop Art is born.

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Sign up to our Free Weekly NewsletterEquipped with his famous platinum blond wig which would be the starting point of his public persona, Warhol began making comic book illustrations. He painted subjects like Popeye or Dick Tracy in the early 1960s but soon discovered that Roy Lichtenstein had preceded him in this.

Warhol then opted for an entirely innovative concept that would make him world-famous: reproducing consumer products. In July 1962, the Ferus Gallery in Los Angeles exhibited his Campbell’s Soup Cans for the first time. The work was made up of 32 canvases each representing a different flavor of soup from the Campbell brand.

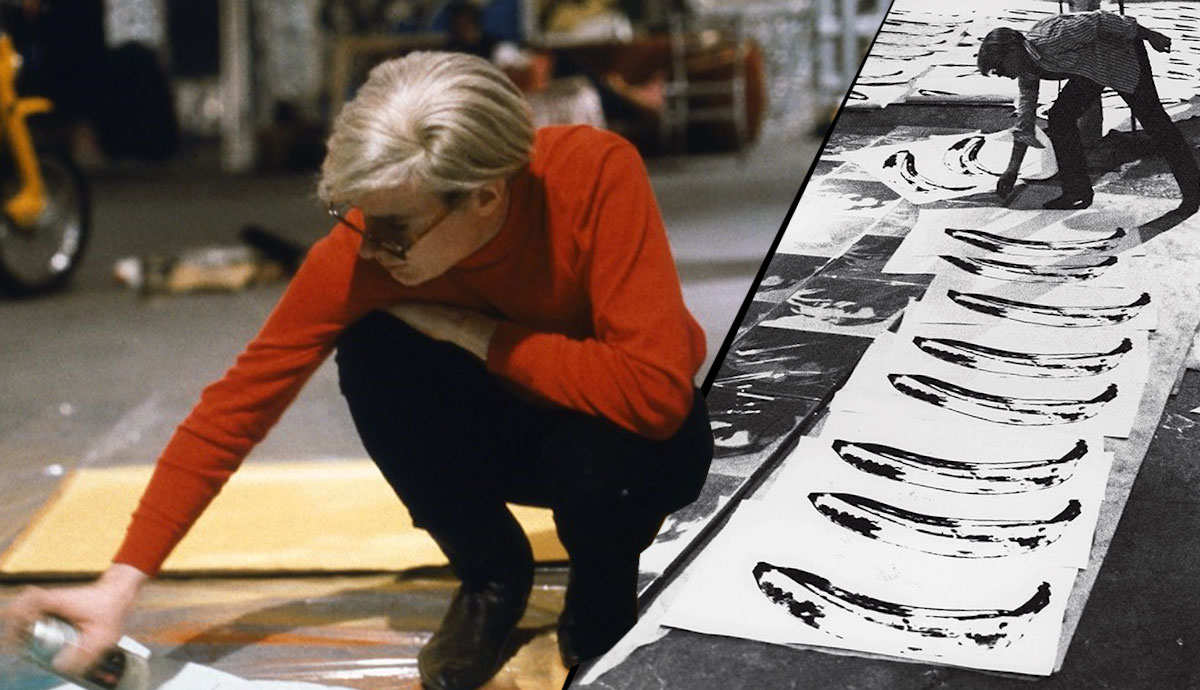

Following this work, Warhol abandoned painting and turned to silkscreen printing. He started using this method from the advertising industry for his art, printing simplified black and white photographs on a large canvas painted with large flat areas of color. He could then reproduce the pattern several times using different colors.

The industrial aspect of his creative process, echoing post-war mass consumption and the dawn of a new American society, was at its peak. The pieces first shocked members of the public who at first did not understand how these common objects could be considered artworks.

Warhol’s early work reveals an inspiration that strongly recalls the French Dadaist Marcel Duchamp’s concept of the Readymade. Both artists used everyday objects and elevated them to the status of works of art, questioning their very essence. They chose to abandon the creative aspect which was fundamental in the artistic process until then. Like Duchamp, Warhol called into question the artistic approach itself.

Despite the controversies initially provoked by Warhol’s artistic production, gallery manager Leo Castelli believed in his potential. In 1962, he allowed the artist to join the first-ever Pop Art exhibition at the Sidney Janis Gallery in New York. His work was met with phenomenal success and his artistic process required new premises. Andy Warhol moved his studio to the firehouse on East 87th Street in January 1963 and a new era for the underground avant-garde scene of 1960s Manhattan began.

Andy Warhol’s Studio at the Factory

In his new studio called The Factory, Warhol fully embraced the industrialization and commercialization of art. He chooses to abandon painting and turn to modern image reproduction techniques through silk screen printing, photography, cinema, and sound. He also surrounds himself with artists and celebrities of all kinds who enriched his artistic universe. Between 1983 and 1985 he collaborated with a young artist called Jean-Michel Basquiat on a series of paintings. At the Factory, Warhol’s multifaceted artistic production challenged the traditional hierarchy of artistic disciplines.

In his Factory, Warhol also embarked on a project that would become one of his legacies: portraits of celebrities. He portrayed movie actors, rock stars, and celebrities like Elizabeth Taylor, Elvis Presley, Jackie Kennedy, and Marilyn Monroe. Monroe’s death in 1962 touched the whole world and the media proceeded to use her image even after her death. Marylin’s face was everywhere. This overconsumption of her image inspired Warhol to create his Marylin Diptych in 1962, followed by several other prints in which he used different colors. But he always used the same photograph of the actress. By reproducing Marilyn’s face he turned her into a symbol of the industrialization of mass media.

The Factory also allowed Warhol the opportunity to experiment with new artistic media. In 1965, he publicly announced that he wanted to give up painting and devote himself to exploring new artistic practices. The following year, the artist became the manager of the rock band The Velvet Underground. Its members were Lou Reed, John Cale, Sterling Morrison, and Moe Tucker. Warhol suggested they should invite German model and singer Nico to join them on vocals.

The band became the heart of the artist’s multimedia happenings and a road show he called Exploding Plastic Inevitable. It consisted of The Velvet Underground playing music while ad experimental films were being projected behind them. Warhol’s so-called superstars like Gerard Malanga and Mary Woronov performed on stage as well. One of their well-known routines was the Whip Dance, a sadomasochist interpretation of some of the songs The Velvet Underground was playing.

The band’s first album The Velvet Underground & Nico was recorded within a few days in 1966 during a performance of the Exploding Plastic Inevitable. It was produced by Warhol. The crude lyrics with subjects like drugs and sexual deviance were controversial, and the avant-garde and experimental sound of Lou Reed’s music was not necessarily well received by the public. The album sold only 30,000 copies at the time of its release.

The album’s iconic cover was, of course, created by Warhol. The band’s name was written only on the back cover, while Andy Warhol’s signature was visible on the front, right under the banana. This caused a lot of confusion when the album was released. Indeed, many people thought that the artist himself had recorded a music album.

Warhol’s Films

Between 1963 and 1968, Warhol’s Factory also served as a Petri dish where more than 650 experimental films were created. Almost like precursor versions of reality TV, most of his films showed everyday life at the Factory, with its Superstars, collaborators, and various guests. His films were intended to be anti-films, that is to say, they were meant to embody the opposite of what a film was traditionally expected to be.

Yet, his works filmed at the Factory are not just an objective presentation of reality: the protagonists are well aware of the presence of the camera and certain parts were indeed staged. For Warhol, it was more about the idea of an immersive work and being able to bring anyone into his universe at the famous Factory. Echoing his Campbell soup cans, he transformed everyday life into art.

His 1964 film Sleep consists of more than 5 hours of footage showing a sleeping John Giomo. The 1965 film Empire is an 8-hour-long slow-motion shot of the Empire State Building. According to Warhol, this movie was supposed to make the public see time go by. These looping and slow-motion techniques are often used in his films to make a shot last as long as possible. He also often filmed in 24 frames per second and projected his images at 16 frames per second, giving an impression of slow motion.

In 1965, Warhol made his muse of the moment Edie Sedgwick shine in the film Poor Little Rich Girl. With a title copied from a Shirley Temple movie, this film did not try to hide the parallels between the original screenplay, which follows a young girl sent to boarding school by her father who ends up joining a vaudeville troupe and Edie Sedgwick’s real life. After being sent off to boarding schools and psychiatric hospitals by her father, Edie moved to New York at the age of 21 with hopes of becoming a model. She soon became a muse of Warhol’s and a regular face seen at his Factory.

In Poor Little Rich Girl, the camera follows Edie on a typical day. We see her alone in her apartment, to the sound of the Everly Brothers’ Crying in the Rain, doing everyday things. Warhol showed the daily life of a poor little rich girl, surprisingly relatable and universal in its loneliness and melancholy.

Warhol’s most famous and acclaimed film was made the following year. It was titled Chelsea Girls and it was his only film that reached a mainstream audience. Shot at the Chelsea Hotel and the Factory in a documentary style, the film follows the daily life of several fictional residents of the hotel played by Warhol’s Superstars and members of his entourage like Nico, Paul Morrissey, Ondine, and Mary Woronov.

Edie Sedgwick was also supposed to appear in it, but she asked for her scenes to be cut out of the movie. The film is presented on a split screen, giving us a glimpse into the New York underground scene of the 1960s. An arthouse masterpiece for some, and an obscene flop for others, Chelsea Girls still divides the audience today.

Andy Warhol’s Factory as the Ultimate Hotspot

Warhol, who never really abandoned his silkscreen printing production, sold his works for large sums of money and used most of it to finance the Factory. After a few months in the firehouse building on East 87th Street, the initial Factory had to move in 1964. Warhol found it a new home on the fifth floor of 231 East 47th Street. The Factory would remain here until 1968. This would turn out to be its golden age.

When the building hosting the Factory was slated for demolition, Warhol moved his studio again. It was now located on the sixth floor of the Decker Building, at 33 Union Square West where The Factory became more of a business office than a social scene. It was there that Valerie Solanas, a radical feminist artist suffering from paranoid schizophrenia, tried to kill Warhol in 1968.

Warhol survived, but this marked the end of the free-spirited and debauched 1960s Factory. It was now harder to get into the American artist’s studio. The last location of the Factory was in a large building on Broadway. Here Warhol mainly devoted himself to screenprinting before his death in 1987.

Until the end of the 1960s, Warhol’s Factory was the hip hangout spot for celebrities and artists from the New York counterculture scene. Musicians like David Bowie or Bob Dylan, iconic poets of the Beat Generation like Allen Ginsberg or William Burroughs, and even actors like Judy Garland or Dennis Hopper all came to the famous Factory at some point. Warhol even created a series of films titled Screen Tests that consisted of black and white portraits of famous personalities that came to visit.

Warhol attracted a whole clique of quirky people that he named Warhol’s Superstars. They were performers, musicians, adult film actors, drag queens, celebrities, socialites, poets, avant-garde artists, and any other bizarre characters with crazy ideas who could inspire him. This whimsical troupe helped Warhol create his screenprints, starred in his films and created the unique atmosphere of the Factory.

Warhol’s first Superstar was Baby Jane Holzer. She appeared in several of his experimental films. The most important personalities of the Factory emerged in its first period, from 1963 to 1968. This machine for forging celebrities produced many names which include Paul America, Ondine, Joe Dallesandro, Mary Woronov, Ultra Violet, Gerard Malanga, Billy Name, Nico, and Edie Sedgwick.

Edie Sedgwick became the symbol of Warhol’s process of creating a celebrity. During their short relationship, the duo was inseparable. Fascinated by Edie, Andy made her his muse and his alter ego. She cut her long brown hair and dyed it platinum blonde to look like the artist. They also wore similar clothes during their appearances in public.

Fashionable, glamorous, and eccentric, Edie became a celebrity without really trying. She was an artist without artwork, an actress of her own life. She might even be the first modern celebrity of the 20th century, famous for being herself.

In this hotspot of underground culture, Warhol always attracted more eccentrics and thinkers. Towards the end of the 1970s, his attention turned to transsexual women and drag queens. Candy Darling, Jackie Curtis, and Holly Woodlawn became his new muses. Lou Reed even immortalized some of the 1960s Warhol Superstars in his famous song Walk on the Wild Side.