Kösem Sultan, initially a concubine, then the wife of the Ottoman Sultan Ahmed I, was a controversial figure even in her own time. She not only exercised power through three different sultans but influenced court politics in her own right. She had her son Ibrahim deposed from power but was eventually assassinated by his wife, Hatice Turhan, an equally ambitious woman.

Kosem’s Humble Beginnings

Kösem’s story begins in the Balkans where she was born as Anastasia in the year 1589. Various sources claim that she was Bosnian, Greek, or Circassian. Kösem was most likely going to live a life like other female villagers of her time: a life filled with fieldwork, household duties, and childrearing. Yet fate had other plans for her.

Although information is scarce, it is known that as a child, she was enslaved and employed in the palace of the beylerbeyi (governor-general) of the province of Bosnia. Realizing that she was a bright and beautiful girl, the beylerbeyi sent her to the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul. During this period, it was common for officials and those seeking the Sultan’s approval to gift talented and promising slaves to the sultan’s palace.

She was given the name Mahpeyker. However, her leadership and guidance of the other girls of the harem earned her the moniker “Kösem.” This term referred to a ram used by shepherds to lead herds of sheep. It can therefore be inferred that Kösem, from a young age, was skilled in controlling and influencing others.

Life as the “Haseki”

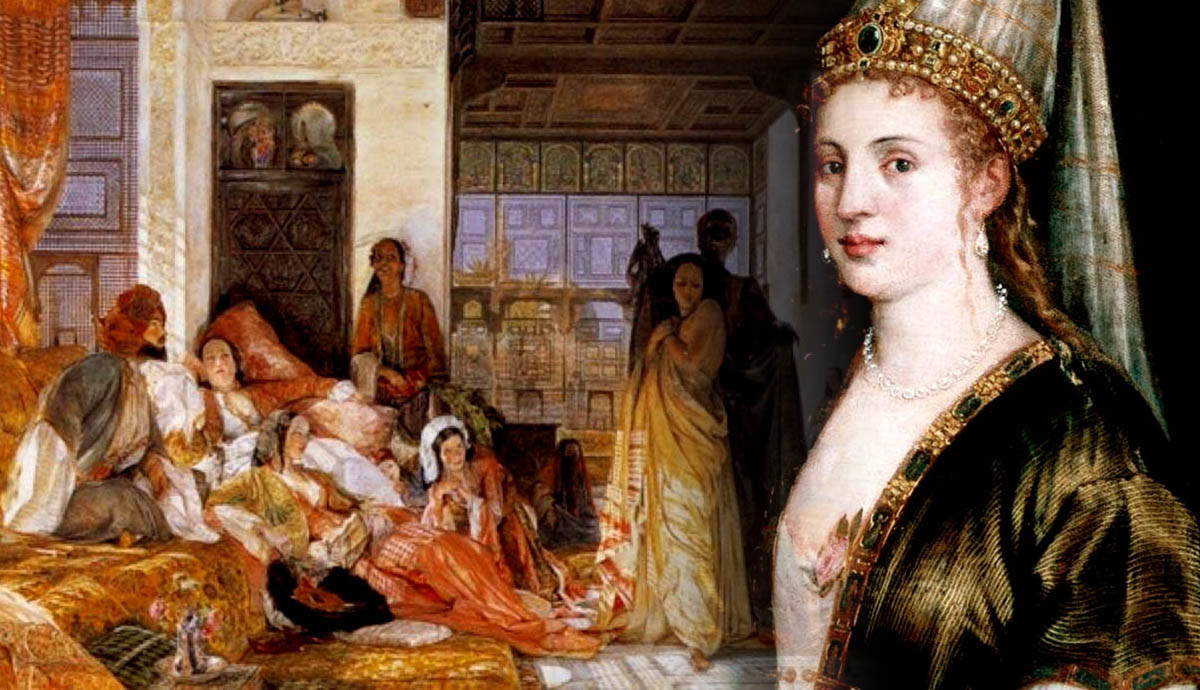

Kösem’s expressive brown eyes, pale complexion, and striking physique weren’t the only things that attracted the attention of the Valide Sultan (Queen Mother) Handan Sultan. The girl’s intelligence and skill in various fields like literature, mathematics, and music made her a good candidate for the future mother of an Ottoman prince.

At around age 15, she became Sultan Ahmed I’s “haseki,” or chief consort, a title first granted to Hürrem, wife of Suleyman the Magnificent. This gave Kösem certain privileges, such as a salary of 1,000 aspers per day. Ahmed was reportedly infatuated with the lively and positive Kösem, who was careful not to interfere too openly in political issues

Still, her intelligence made her an important advisor to the Sultan. According to the Venetian ambassador Contarini, she was “listened to in some matters.” Her role in governance was later remarked upon by the English envoy Thomas Roe, who noted that Kösem had “governed” Sultan Ahmed.

When Ahmed’s powerful grandmother Safiye Sultan was banished to the Old Palace, and his mother Handan Sultan died in 1605, a special opportunity presented itself to the ambitious Kösem. In the absence of other senior female figures, the already commanding Kösem took charge of harem politics. Her influence was not only exercised over the Sultan—who eventually married her—but also over major court officials like Mustafa Ağa, leader of the janissary corps.

Kösem and Court Politics

Ottoman court politics in the early 17th century was plagued by several issues. Ottoman power was decreasing with losses in wars across Europe. Queen mothers and Hasekis were competing for power and influence in a period dubbed the “Sultanate of Women.” Added to this was the introduction of child sultans (starting with Ahmed I).

Kösem was immediately introduced to this world when she entered the palace and witnessed the old Valide Sultan Safiye being sent away from the palace to be replaced by Ahmed I’s mother, Handan. Yet, instead of being crushed by this system, Kösem adapted to it. She gained the respect of the Valide Handan Sultan and treated Ahmed’s children from his other concubines as her own.

She likewise maintained a good relationship with Ahmed’s half-brother Mustafa and convinced the Sultan not to have his brother killed. This would later benefit her children; Should Mustafa come to the throne one day, he would be merciful towards Kösem’s sons and not institute the policy of fratricide, where a sultan would have his brothers executed to ensure political unity.

Following the death of Ahmed in 1617, his half-brother Mustafa was indeed declared sultan. However, due to Mustafa’s questionable mental state, he was replaced by Ahmed’s son Osman II. Osman’s efforts to institute state and military reforms gained him many enemies, and at 18 years old, he was imprisoned and murdered. Mustafa once again acceded to the throne. This time, however, it was Kösem who would put an end to his reign.

Becoming the “Valide Sultan”: Queen Mother

To ensure both her children’s security and her own, Kösem wanted her son Murad to become sultan. She achieved this goal by gaining the support of courtiers and viziers. In 1623, Murad IV became sultan at age eleven. Since he was a minor, his mother Kösem had to take power. For the first time in 300 years of Ottoman rule, a woman assumed the official title of regent.

Kösem was an apt political player. She attended the divan meetings—albeit from behind a screen—during which the viziers discussed important state affairs. She also was in correspondence with foreign ambassadors and statesmen. Her kira, or agent, was a Jewish woman who would often write her letters for her and represent the valide in meetings with male dignitaries or tradesmen.

Yet Kösem’s regency was rocked by political and economic instability. Uprisings, raids, and wars threatened the Ottoman state throughout the 17th century. Economic issues also arose due to a loss of territories like Baghdad and the plague in Egypt, which was a major revenue source for the Ottoman state.

Despite Kösem’s efforts in battling inflation and appeasing the dissatisfied janissary troops, her son Murad had come to see his mother’s power in a negative light. After nine years of rule, Kösem was distanced from power by her son. Her most loyal courtiers and companions were also removed from power and replaced by individuals who supported Murad.

Here Comes Trouble

Kösem’s ambitious nature would not allow her to lead a life removed from political power. When her son went on military campaigns, she was formally left in charge of the empire. In addition to running the harem, she advised her son on important political issues like executions and diplomatic proceedings.

When Murad fell ill, the Ottomans realized that their state was in serious threat of ending. The Sultan had executed all but one of his four brothers: Ibrahim “the Mad.” Kösem had managed to dissuade Murad from executing Ibrahim, arguing that he was mentally ill and therefore not a threat to Murad’s power. As a result, on Murad’s death in 1640, Ibrahim was declared Sultan. Kösem once again became the valide, this time exercising power over a mentally unstable adult son.

But she had not factored in how Ibrahim’s mental instability would play out. The sultan’s erratic personal relationships, his lustful obsession with women and his tendency to act violently when displeased were among some of the factors that made him unpopular at court. Kösem, like the religious and political elite, believed that getting rid of Ibrahim would be beneficial to the state.

In his youth, Ibrahim had lived under house arrest in the kafes (a restricted part of the Harem) and was paranoid about being assassinated. Though he was now free, this fear became a reality when Kösem conspired to have him removed from power. Although it is said that she only wished for him to be imprisoned in the kafes, he was eventually strangled in 1648.

Assassinating the Queen Mother

After Ibrahim’s murder, his six-year-old son Mehmed IV was put on the throne. As a child, Mehmed was to rule through a regent. Naturally, this would be his mother, Hatice Turhan Sultan. However, Kösem refused to relinquish power so easily, and a dangerous rivalry began between the two women.

Hatice Turhan was the official Valide Sultan and therefore had more right to power. To counteract this, Kösem had herself declared Büyük (elder) Valide. The court also became highly factionalized due to this competition; Hatice Turhan wanted Siyavush Pasha to become the grand vizier, while Kösem preferred Melek Ahmet Pasha, the husband of her granddaughter Kaya Sultan.

This rivalry, and the political turmoil that followed, was possibly a major factor that led to the assassination of Kösem. In 1651, eunuchs entered Kösem’s quarters and strangled her to death, according to some accounts with her own braids. The news of Kösem’s death caused a degree of civil and social disorder. Crowds gathered near Topkapi Palace demanding revenge on Kösem’s murderers, and the city went into mourning for three days.

Another Side to Kösem?

Kösem has been depicted in various ways throughout the ages. Her contemporaries, too, had differing views about her. The Venetian ambassador Contarini said that she was generally respected. English traveler George Sandys, however, noted that she had an unnatural influence over the Sultan because she was a “witch.”

Kösem was also a controversial figure among the local populace. Prominent Ottoman theologians and statesmen argued that her immense wealth was a result of financial abuse in a period that saw poverty and inflation.

Others praised her charitable acts: Kösem built mosques, fountains, and madrasas (institutes of theological teaching), built in the Ottoman architectural style around the empire. As a former slave, she perhaps even felt some sympathy towards other enslaved women. Ottoman historian Mustafa Naima (d.1716) wrote that Kösem would free her female slaves after two to three years of service. Additionally, she would give them an annual wage, and have them married.

Like other politically-savvy women throughout history, Kösem was a product of her environment. This was a male-dominated world in which she had to fight to survive and prosper.