The French Impressionism movement was groundbreaking in many ways. It challenged academic standards put in place by the high-class Parisian salon. It set the foundation for the development of later art movements such as Cubism and Surrealism. Most importantly, it destroyed the assumption that only perfect, ideological images could be considered art. Rather than depicting nymphs and goddesses from mythology or idealized figures of exotic women lounging in a Turkish bath, the Impressionists went into the streets and painted the real world, shattering the illusion of perfection for something more genuine and raw.

Nothing accomplished this more than a few artists’ explorations into the world of prostitutes. They drew these women without prejudice. Rather, there is an element of curiosity that comes with these male artists exploring a feminine world largely unknown to them. Read on to discover what really went on in 19th-century brothels through an analysis of 4 French paintings.

Inside France’s 19th-Century Brothels

The sex work business boomed, especially during the second half of the 19th century. During this time, prostitution was legal and regulated in France, a law very fitting for the country of love, where every noble had his courtesan and every man his mistress. Prostitution was seen as a necessary evil to “blunt the rampant nature of the male libido.” Sex workers who registered themselves with the local police and received a health inspection twice a week were permitted to work in one of the nearly 200 state-controlled legal brothels or maisons closes. However, this did not eliminate the illegal and unregulated prostitution industry that was also quite prevalent in the streets of major French cities.

With the popularization of the prostitution industry came many artists of French Impressionism hoping to get a peek inside these 19th-century brothels. They wanted to paint this mysterious world and get to know the women in it. Depictions of prostitutes were often romanticized, and the lifestyles of those women on the moral fringes of society fascinated many. Before Impressionism, artists tended to depict prostitutes as either goddesses from mythology or as “exotic” women so as to maintain a separation between fantasy and reality. However, as time went on and artistic concepts changed, so did the representation of what went on inside the 19th-century brothels.

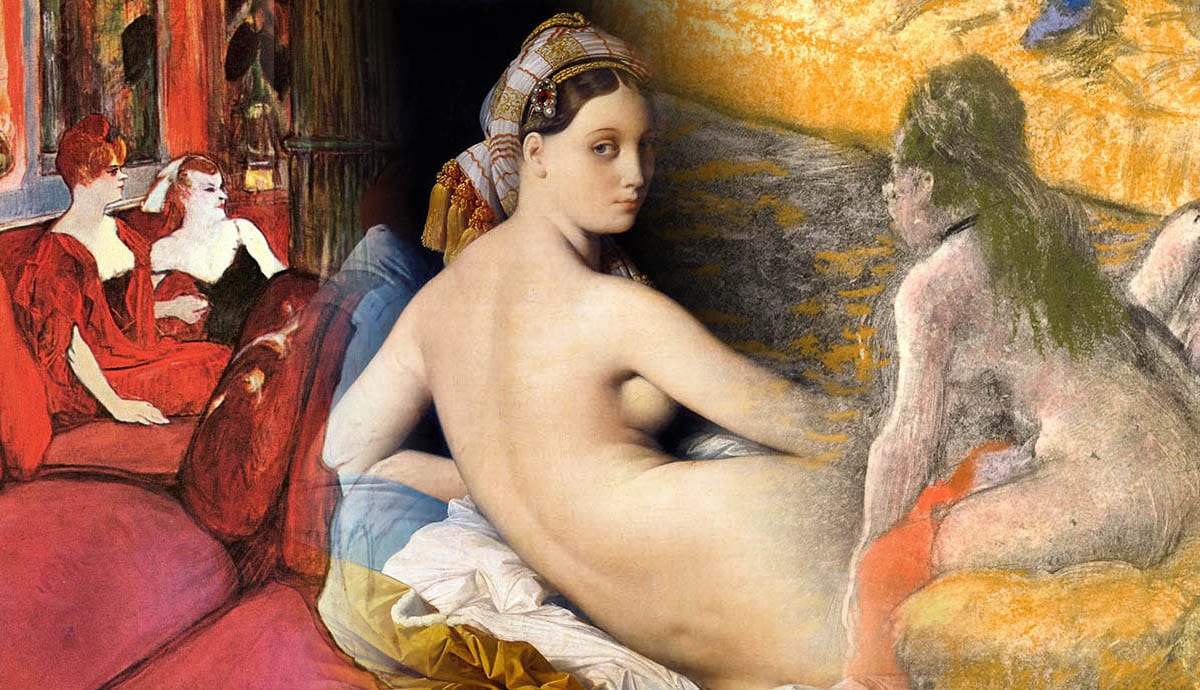

1. Grande Odalisque, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, 1814

Painted in 1814, Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres created Grande Odalisque well before French Impressionism rocked the Parisian art world. However, this oeuvre presents an excellent example of how prostitutes were depicted during Orientalism as well as how depictions of the female nude evolved.

Ingres started as a painter belonging to Neoclassicism, but this painting can be seen as his departure from this movement and toward a more Romantic style. Reclining and looking back at us, Ingres’ Odalisque is a woman not of this world. Her body is soft and rounded, with a complete lack of anatomical realism. This makes her figure sensuous and inviting, and her gaze looking back at the viewer is one of allure and temptation. However, when exhibited in the Parisian Salon in 1819, Ingres’ Odalisque was met with harsh criticism due to the artistic liberties that Ingres had taken with human anatomy.

Ingres sets his subject in a Turkish harem rather than a French 19th-century brothel. Being from the “Orient” renders the woman all the more exotic and alluring but also builds up a fantasy around her character and life. According to Ingres, a prostitute was someone exotic, sensual, and mysterious. Although progressive in terms of artistic style, his work was still a far cry from the real world.

2. Olympia, Édouard Manet, 1863

Painted in 1863, Olympia was Édouard Manet’s next submission to the Salon after they rejected his first controversial piece, Le Déjeuner sur l’Herbe. Olympia was not the ideal goddess the Parisian Salon was familiar with nor approved. She confronts the viewer with a cold and uninviting stare, not at all submissive to the male gaze. Manet “reworked the traditional theme of the female nude, using a strong, uncompromising technique.”

He alluded to numerous formal and iconographic references, including Titian’s Venus of Urbino, yet managed to create something wholly revolutionary and groundbreaking. According to its description in the Musée d’Orsay, Manet’s Olympia shows the changing of times in the French art world: “Venus became a prostitute, challenging the viewer.”

The turning away from erotic paintings of Greek and Roman deities and toward the ladies working in 19th-century brothels signaled a beginning to the desexualization of the female nude. Manet, in particular, focused more on the reality of prostitution: his painting lacked the fantasy of Turkish baths and mythological symbolism that used to be present in such paintings. Instead of female sexuality, he called attention to the woman’s power over the commercial transaction – which can be noted in the position of Olympia’s hand: according to James H. Rubin in his book Impressionism: Art and Ideas, it “covers up yet calls attention to the commodity for sale” (65).

Manet felt he could relate to prostitutes, not because he felt like an outcast but because of his position as an artist. In making the subject a prostitute, he alludes to Charles Baudelaire’s work The Painter of Modern Life, drawing a parallel between art and prostitution. Baudelaire argues that since art is a form of communication that requires an audience, “the artist must, like the prostitute, exhibitionistically attract his clientele by the means of artifice.”

Edouard Manet’s 1863 painting Olympia paved the way for other depictions of prostitution, namely those works of Edgar Degas and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec. Both were able to bring it one step further by going into the actual brothels and painting real prostitutes.

3. Waiting For A Client, Edgar Degas, 1879

Degas’ monotype Waiting for a Client marked the time when artists began to paint outside of their studios, en plein air in the countryside and inside les maisons closes of the city: inside France’s 19th-century brothels. In his depiction of prostitutes waiting for their next patron, Edgar Degas shows the alienation from the outside world by adding a male presence to the scene. This figure is severely cropped, but by adding the fully dressed man just out of the frame among all of the nude women, Degas effectively blurs the world between the private life of prostitutes and elite Parisian society.

The effect of the male presence inside this 19th-century brothel can be felt through the women’s tensed poses. Degas portrayed the prostitutes as if they were characters in a play, not fully relaxed. The prostitutes know they have to put on a façade for their new client; they must don the alluring and sensual character that made people fascinated by their lifestyle.

Here again, Degas’ prostitutes, although nude and in the presence of a man, are not in the least sexualized. These women instead play a role in the commentary Degas makes on the irony of severe societal differences that occasionally mesh in certain settings, the 19th-century brothel being one of them.

4. Maisons Closes (In The Salon At The Rue Des Moulins), Henri De Toulouse-Lautrec, 1894

In his painting Maisons Closes (In the Salon at the Rue des Moulins), Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec focused on the fact that a life of prostitution is a life without glamor. It was not so luxurious inside of these 19th-century brothels.

He presented them with respect but without the sensationalism or idealization that one can find in Orientalist paintings of odalisques and Turkish baths. Instead of soft round bodies and inviting, come-hither faces such as those painted by Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres, these women have resigned faces and tired eyes, are in varying stages of dress, and all have reserved body language. They do not engage with each other, showing their alienation from one another despite being in the same situation.

He did not idealize his figures nor turn them into something pleasing for the male gaze. In Maisons Closes, Lautrec provided a glimpse into the sordid world of prostitution, giving the viewer a sympathetic look at the boredom these women often experience in their daily life.

Toulouse-Lautrec was particularly interested in this world. He drew his subjects without judgment and without sentimentality because he felt as though he were one of them. Due to the sad circumstances of his personal life, Lautrec felt as though the prostitutes he painted shared something in common with himself – they were outcasts, relegated to the fringes of society. He was a frequent visitor and probably even kept an apartment at Le Chabanais, one of the most notorious and prestigious Parisian brothels. In Maisons Closes, he portrayed these women as individuals, neither talking or interacting with one another.

The 19th-Century Brothel: Artistic Inspiration And Crude Reality For French Impressionism

Apart from Ingres’ Grande Odalisque, which came before French Impressionism, these works of art are similar in that the portrayals of prostitutes are hardly sexualized. They are instead realistic and almost crude, especially since all three are set inside the intimate space of a brothel or a bedroom. However, it is important to note that Manet’s piece was much more sensationalized than the works of Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec because it was one of the first times the general public had seen a female nude depicted so candidly.

Olympia was one of the first paintings to really challenge the rigid academic standards, while Degas’ Waiting for the Client and Lautrec’s Maisons Closes were produced when depictions of prostitutes were much more common, especially among the Impressionist community. On the other hand, Manet painted Olympia in the studio using a model instead of going into a brothel and painting actual prostitutes as Degas and Lautrec did. This admittedly can take away from the element of truth and vulnerability found in these depictions of the real world of prostitution.

Thanks to the work of French Impressionism artists, people now recognize the small aspects of daily life as beautiful and acknowledge that even those on the margins of society can be art. Edouard Manet set in motion a movement of artists who challenged academic norms while Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec embraced this new wave of artistic expression and carried it forward. These works have the capability to both delight and shock the viewer. Furthermore, they can teach us many lessons on the grim reality that is the world of prostitution.