Since the 1960s the art world has seen a growing number of artists from around the world, many of whom leave their home countries. These artists negotiate with global trends while becoming hyper-aware of how their racial and cultural identities are perceived in the west. Here we will look at four South Asian diaspora artists their fascinating artworks.

The Gray Zone of the South Asian Diaspora

Migration is one of the many fundamentals upon which Modern and Pre-modern societies have built themselves. Migrants from South Asia have been on the move since early Premodern times (before the 1800s) supplying themselves to a larger demand for military, artisanal, and agrarian labor. The term South Asia is used to indicate the southern part of the Asian Continent. This includes Afghanistan, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Bhutan, and the Maldives.

Diaspora artists are those who migrate from one part of the world to another. They often inhabit a gray zone, that of outsider and insider both. These contemporary artists challenge the notion of cultural boundary zones, belonging, language, and homemaking. What precedes them is their South Asian identity, and what follows is their hybridity.

Sunil Gupta and Queer South Asia

Born in 1953 in India, photographer Sunil Gupta spent his teens in Montreal. He studied photography in New York in the 1970s, and in 1983 received a Master’s in London where he lived for the next two decades. Afterwards he returned to India in 2005, despite the channels of risk he faced due to the public health crisis and the criminalization of homosexuality at the time. In 2013 he relocated to London.

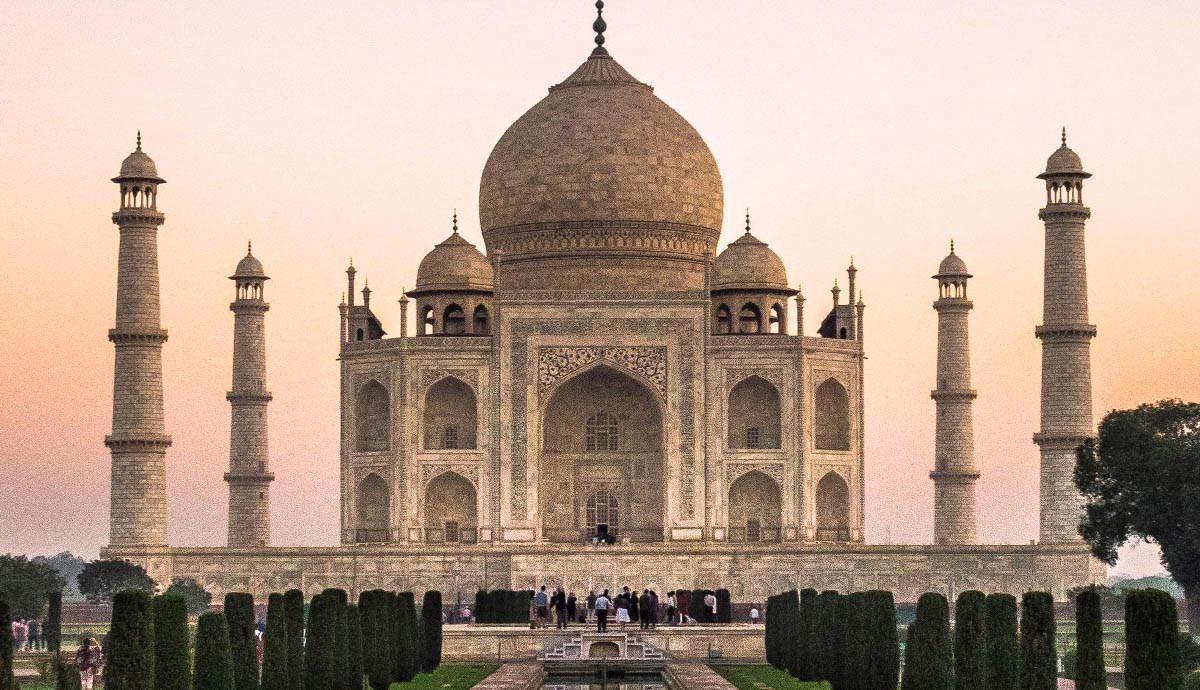

Gupta navigates the grey zone of an insider-outsider space not just in the West but also as a gay man in his home country. In his early series called Exiles (1986), the artist reclaims Indian history and public spheres as sites of queer sexuality and identity by locating gay men in iconic architectural and historic spaces. When Exiles was shot, homosexual acts were punishable by up to ten years in prison, and gay life in India was heavily concealed.

Gupta’s mural-size work, the Trespass series, created in the early 1990s (1990-92) explores the hybrid intersections of multiple social and personal histories. Utilizing digital technology, Gupta combined his photographs, archival images, ads, and other popular source material. In the years 1990-92, Gupta turned his eye to the alienness of being a stranger in a strange land, focusing on the experiences of the South Asian diaspora in a newly unified Europe. He undertook this project in Berlin, juxtaposing historical photographs of Nazi Germany, war monuments, advertisements, and photographs of unidentified South Asians, along with portraits of himself and his British partner.

Gupta’s work has and continues to negotiate with his diasporic identity by exploring the complex interaction of sexuality with all the other factors that migration brings. He shows how queer life finds itself at odds with the orthodoxies of both his home and host cultures. That’s what makes his work particularly interesting.

Shahzia Sikander’s New Miniatures

When it comes to the role played by South Asian Diaspora artists in the reinvention of traditional practices and techniques, Shahzia Sikander always comes to mind. Pakistani artist Shahzia Sikander takes the miniature art form, essentially a courtly practice, and reinvents it using new scales and technologies, cultivating the hybridism of a diaspora artist. Miniature or Manuscript painting has long been associated with South Asian and Middle Eastern art history. Inspired by the Persian Safavid dynasty (1501-1736) it made its way to South Asia. This miniature art fused with indigenous forms and styles, namely Jaina miniature painting (12th to 16th century) and Pala painting (11th & 12th century). This led to the formation of the well-known Mughal miniatures (16th to mid-19th century) which greatly inspired Sikander.

Sikander led the miniature revival movement as a young student at the National College of Arts, Lahore, in the early 1990s, and later moved to the United States. She has often complained about the art establishment in Pakistan, where she said that a number of people viewed her as an outsider at home. Sikander only presented her work for the first time in Lahore, the city where she grew up, in 2018. Sikander uses idioms from medieval and early modern Islamic and South Asian manuscript painting, transforming it into a tool for critical inquiry.

Sikander’s Maligned Monsters I, (2000) borrows its name from Partha Mitter’s book Much Maligned Monsters (1977). Mitter’s study charts the history of European reactions to Indian Art, highlighting the so-called ‘exotic’ Western interpretations of non-Western societies. In her take, archetypes of the divine feminine are presented shoulder to shoulder. The figure on the right is draped in the form of the Graeco-Roman Venus attempting to conceal her nudity, while the figure on the left wears an antariya, an ancient garment from the subcontinent. By bringing together these two decapitated female forms from two vastly different cultures, joining them through Persian Calligraphic forms, we see the work as Sikander’s personal negotiation with her diasporic identity.

In Many Faces of Islam (1999), created for the New York Times, two central figures hold between them a piece of American currency inscribed with a quote from the Quran: Which, then, of your Lord’s blessing do you both deny? The surrounding figures speak to the shifting global alliances between Muslim leaders and the American empire and capital. The work includes portraits of Muhammad Ali Jinnah (founder of Pakistan), Malcolm X, Salman Rushdie, and Hanan Ashrawi (spokesperson for the Palestinian Nation), among others. The Many Faces of Islam brings forth the reality that after globalization, no nation or culture lives in a vacuum. Now more than ever, we are faced with the pervasive diasporic viewpoint.

Runa Islam Smashing Teapots

The tensions of having dual or multiple heritages surface very clearly in Bangladeshi-British artist Runa Islam’s work. Her first major video work was Be the First to See What You See as You See It (2004) and it was nominated for the 2008 Turner Prize. It features a woman whose spatial interaction with her surrounding objects criticizes the illusion of a unified cultural identity.

In the film the viewers see a woman in a confined room, observing porcelain. To the viewer, the woman is as much on display as the porcelain on the table. After a while, the woman begins having tea in a peculiarly British manner. After moments of tense silence, the woman begins pushing the porcelain pieces off the tables.

According to John Clarke, a reputed scholar of Modern and Contemporary Asian Art, it is no coincidence that Islam chose to smash teapots and cups, which are traditional symbols of the British gentry. The work can be read as a critique of England’s colonial past. Islam confronts her current situation as a Bangladeshi-British artist while reflecting on Britain’s colonial impact on Bangladesh and its confinements.

Mariam Ghani and the Index of the Disappeared

Collaborations among diaspora artists often bring to the surface the unique racial and religious awareness the diaspora identity brings to certain individuals. A year after 9/11, 760 men had disappeared in the United States. These people were classified as special interest detainees by the Department of Justice and were largely men between the ages of 16-45 from South Asian, Arab, and Muslim countries that were residing in the US.

In response, Afghan American artist Mariam Ghani and Indian-origin American artist Chitra Ganesh devised an Index of the Disappeared in 2004, an ongoing, research-driven, multipart investigation into the post-9/11 security state’s racialization of disappearance and its documentation. Now into its eighteenth year, Ganesh and Ghani’s art project exists in two principal forms. First, as a physical archive of post- 9/11 disappearances encompassing DVDs, articles, news, legal briefs, reports, zines, and ephemera. Second, the project has publicly appeared through the form of organized events and art installations, in response to the War on Terror. To date, Index of the Disappeared has been researched within accounts of a broader artistic counterculture after September 11.

South Asian Diaspora and Hybrid Novelty

All four artists share in their work the issues of belongingness, and constant questioning of the idiom of home, revealing the multi-layered nature of human cross-cultural experiences. These artists proactively engage the concept of a nation and the illusionistic nature of the many forms of nationalism, be it fundamentalism, colonialism, or imperialism. The hybridity of the South Asian Diaspora is very similar to Homi K Bhabha’s hybridity which translates elements that are neither the One nor the Other but something else. This brings a certain newness to the world. Bhabha has even ascribed such hybridity to the work of the sculptor Anish Kapoor.

Diasporic artists often bring novelty to the world offering unique perspectives. Every geographical coordinate intermingles with its own unique cultural upbringing, which is then confronted with its far-off relatives. And when such confrontations have artistic modes of thought they bring about artists like the ones mentioned above.