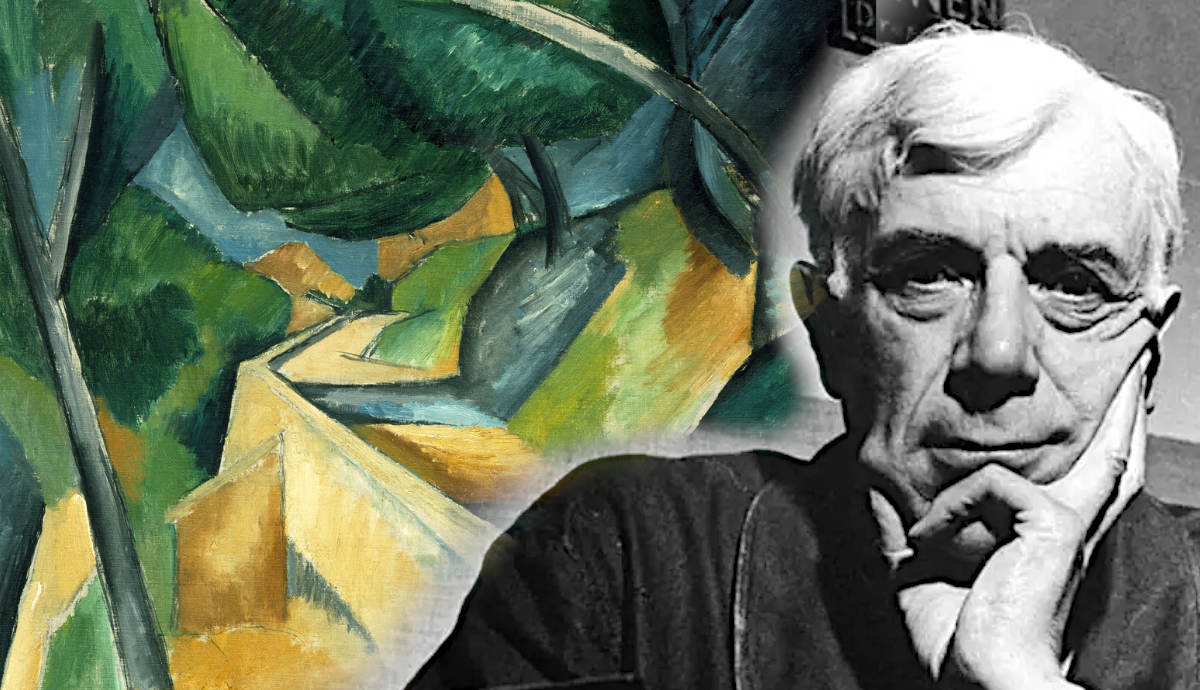

Although often mentioned in conjunction with Picasso and their joint contributions to the art world, Georges Braque was a prolific artist in his own right. Here are six interesting facts about Braque that you perhaps never knew.

1. Braque Trained to Be a Painter and Decorator with His Father

Braque attended Ecole des Beaux-Arts but he disliked school and wasn’t an ideal student. He found it stifling and arbitrary. Still, he was always interested in painting and planned to paint houses, following in the footsteps of his father and grandfather who were both decorators.

His father seemed to be a positive influence on Braque’s artistic inclinations and the two would often sketch together. Braque also rubbed elbows with artistic greatness from an early age, once in particular when his father decorated Gustave Caillebotte’s villa.

Braque moved to Paris to study under a master decorator and would go on to paint at the Academie Humbert until 1904. The very next year, his professional art career began.

2. He Served in WWI

In 1914, Braque was drafted to serve in World War I where he fought in the trenches. He suffered a serious wound in his head that left him temporarily blind. His vision was recovered but his style and perception of the world were forever changed.

After his injury, from which it took him two years to fully recover, Braque was released from active duty and he received the Croix de Guerre and Legion d’Honneur, two of the highest military honors one could receive in the French armed forces.

His post-war style was a lot less structured than his earlier work. He was moved by seeing his fellow soldier turn a bucket into a brazier, coming to the understanding that everything is subject to change based on its circumstances. And this theme of transformation would become a big inspiration in his art.

3. He Was Close Friends with Pablo Picasso

Before Cubism, Braque’s career began as an Impressionist painter and he also contributed to Fauvism when it premiered in 1905 thanks to Henri Matisse and Andre Derain.

His first solo show was in 1908 at Daniel-Henry Kahnweiler’s Gallery. That same year, Matisse rejected his landscape paintings for the Salon d’Automne for the official reason that they were made of “little cubes.” Good thing Braque didn’t take the critique too hard. These landscapes would mark the beginnings of Cubism.

From 1909 to 1914, Braque and Picasso worked together to fully develop Cubism while also experimenting with collage and papier colle, abstraction, and forfeiting as much “personal touch” as possible. They wouldn’t even sign much of their work from this period.

Picasso and Braque’s friendship waned when Braque went off to war and upon his return, Braque received critical acclaim on his own after exhibiting at the 1922 Salon d’Automne.

A few years later, the renowned ballet dancer and choreographer Sergei Diaghilev asked Braque to design two of his ballets for the Ballet Russes. From there and throughout the ‘20s, his style became more and more realistic, but to be honest, it never strayed too far from Cubism.

Along with Picasso, Braque is the undeniable co-founder of the prolific Cubism movement, a style he seemed to hold dear to his heart for all his life. But, as you can see, he did experiment with art in many ways throughout his career and deserved his title as a master on his own.

4. Braque Would Sometimes Leave a Painting Unfinished for Decades

In works like Le Gueridon Rouge which he worked on from 1930 to 1952, it wasn’t unlike Braque to leave a painting unfinished for decades at a time.

As we’ve seen, Braque’s style would change noticeably over the years which meant that when these pieces were finally completed, they’d feature his earlier styles interjected with however he was painting at the time.

Perhaps this unbelievable patience was a symptom of his experiences in World War I. Regardless, it’s impressive and rather unique among his peers.

5. Braque Often Used a Skull as His Palette

After his traumatizing experience serving in World War I, the impending threat of World War II during the ‘30s left Braque feeling anxious. He symbolized this anxiety by keeping a skull in his studio that he often used as a palette. It can sometimes be seen in his still-life paintings, too.

Braque also loved the idea of objects that came to life with human touch such as a skull or musical instruments, another common motif in his work. Perhaps this is just another play on how things transform depending on their circumstances – another bucket to brazier situation.

6. Braque Was the First Artist to Have a Solo Exhibition at the Louvre While Still Alive

Later in his career, Braque was commissioned by the Louvre to paint three ceilings in their Etruscan room. He painted a large bird on the panels, a new motif that would become common in Braque’s later pieces.

In 1961, he was given a solo exhibition at the Louvre called L’Atelier de Braque making him the first artist to ever be awarded such an exhibition while still being alive to see it.

Braque spent the last few decades of his life in Varengeville, France and was given a state funeral upon his passing in 1963. He’s buried in a churchyard on top of a cliff in Varengeville along with fellow artists Paul Nelson and Jean-Francis Auburtin.