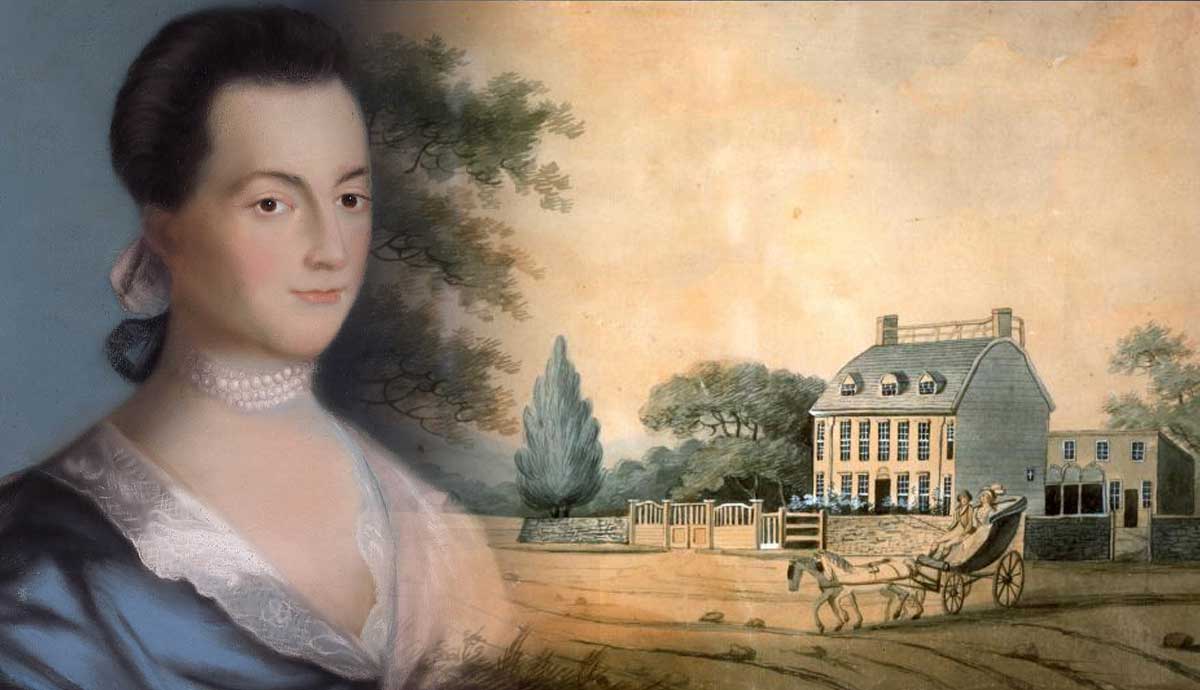

Few women were as outspoken or involved during the American Revolution as Abigail Adams. She helped to keep her husband apprised of local happenings while he was away and provided thought-provoking questions and opinions which helped to form the way the Constitution was written as well as how the early American government was portrayed. Her life was not easy, but she endured and is thought to be one of many important influencers of the American Revolution. She is also thought to be one of the very first female political activists.

Early Life, Courtship, & Marriage

Abigail Smith Adams was born to a minister and daughter of the Speaker of the Massachusetts Assembly. The second of four children, she was not provided a formal education but had a yearning for books and loved to read. She was taught to read and write at home and had access to large libraries from her maternal grandfather. This helped cultivate her interests in philosophy, classic poetry, history, government, and law.

Abigail was not a social butterfly and did not spend her time playing cards or singing and dancing as many of the younger colonists did. Instead, she corresponded with family and friends, often suffering from poor health and remaining at home. In 1759, John Adams first met Abigail and fell in love. Abigail was just 15, and her parents insisted upon a long engagement. They were finally married in 1764 by Abigail’s minister father. Between the start of their courtship in 1762 and throughout John’s political career through 1801, they exchanged over 1100 letters.

During two months, when John was away being inoculated against smallpox, they exchanged 16 letters of love, devotion, and promise. This transitioned into letters of support, opinion, and advice as the Revolution began. Through her correspondence, historians could really dive into the ways of life and the struggles that faced each family. Her descriptive and telling letters are a treasure trove of information and a definitive glimpse into life during the Revolutionary Era.

Family Life during the Revolution

Abigail bore six children, three sons and three daughters, the last of which was stillborn. The first, Abigail “Nabby” Amelia Adams Smith, was born just nine months after John and Abigail were married. Her second child, John Quincy Adams, would go on to follow his father’s legacy in politics and become President himself.

They initially resided at John’s small farm in Braintree, Massachusetts (now Quincy), and Abigail took up the duties of both mother and father, with John gone for periods at a time. Eager to grow his law business and help with the revolution, John set out as a traveling lawyer and circuit judge. His hard work, determination, and sometimes overly brash manner earned him a reputation as a fervent political activist and supporter of the American Revolution. During this time, Abigail took on the duties of parenting, schooling the children, tending to the house finances, farm, and continuing to correspond with John regularly. In doing so, she began to cultivate a strong belief in equal rights and advocated strongly for public schools equal for both boys and girls.

In 1774, John went to Philadelphia to attend the first Continental Congress as a delegate of the colony of Massachusetts. This separation really prompted the correspondence that became a lifelong archive of their relationship, marriage, political and public issues of debate, as well as the revelation that Abigail was a political activist herself. More so, John seemed to rely on her opinion and her advice.

The letters reflect Abigail’s advice to John regarding the political issues facing the colonists and revolutionists at the time, but also observations of the political events around New England. John would often pose questions to her, looking for her honest opinion and observations. In fact, in 1775, as the Revolution was beginning, Abigail was appointed by the Massachusetts Colony General Court along with two other prominent and headstrong women to question fellow women as to their loyalty to the Crown.

Upon hearing of her appointment, John wrote: “…you are now a politician and now elected into an important office, that of judges of Tory ladies, which will give you, naturally, an influence with your sex.” Her observant reporting of citizens’ reactions and responses to legislation and news was opening doors for her as well.

Remember the Ladies

As the revolution progressed, a second meeting of the Continental Congress took place. It was during this time that Abigail wrote to John urging him and the other members of the congress to not forget about the women when fighting for America’s independence. Although a private letter between husband and wife, it reveals much more about the status of women and their fight for equal rights.

In part of that letter, Abigail wrote,

“I long to hear that you have declared an independency. And, by the way, in the new code of laws which I suppose it will be necessary for you to make, I desire you would remember the ladies and be more generous and favorable to them than your ancestors. Do not put such unlimited power into the hands of the husbands. Remember, all men would be tyrants if they could. If particular care and attention is not paid to the ladies, we are determined to foment a rebellion, and will not hold ourselves bound by any laws in which we have no voice or representation.”

Abigail, although not formally educated, clearly understood the need for equality and the eradication of tyrant behavior. And while this would take another 150 years to even come to fruition legally in America, she could be considered one of the first American female political activists. Her thirst for political and public knowledge through books, newspapers, and correspondence with others shows why her husband relied upon and respected her advice and opinion. She was likely his most trusted confidant throughout their life together.

Separated from John

Separation was common for the Adams’s as John always seemed to be away from home pursuing important political tasks. While the Revolution raged at home, John was assigned diplomatic service as Minister to France in 1777. Although a bit more difficult to deliver, Abigail began writing letters to John overseas, keeping him apprised of the domestic affairs in the new country. John, in turn, informed her of international affairs.

John returned to Braintree briefly in 1779 before visiting the Dutch Republic to secure their assistance in the war. Not finding the assistance he was hoping for, he returned to France and continued his negotiations with the treaty of Paris to end the war. The overseas correspondence resumed and continued until 1784, when Abigail joined John in France. There, she toured France before his appointment to Britain as the first American Minister moved them to England. She took notice of the way the French acted and dressed. She found interest in the theater and opera despite being overwhelmed by the largeness of life in Paris.

Shortly thereafter, they moved to London, where Abigail was not accepted and often given the cold shoulder by many. Despite the downfalls of London society, Abigail did her best to play the role of Diplomat’s wife, hosting the upper class as necessary and maintaining a tactful personality. One of the more pleasant parts of her time in London was the temporary guardianship of Mary (Polly) Jefferson, Thomas Jefferson’s young daughter. Ten years after his first assignment abroad, the Adams’ returned to the United States and their property in Quincy, known as Peacefield. Abigail worked fervently to enlarge and remodel the home, and today it is open to the public as part of the Adams National Historical Park in Massachusetts.

The Second First Lady

When John and Abigail returned to the United States in 1788, they soon found themselves as the first Vice President and first Second Lady. She befriended Martha Washington, helping with official entertaining using her experience abroad to ensure proper decorum. Once John was elected President in 1797, she continued the formal entertaining in their Presidential residence in Philadelphia. She held large dinner parties weekly and made many public appearances.

Unfortunately, Abigail was not able to be present for John’s inauguration as the second President of the United States. Instead, she was attending to his dying mother. And although Abigail suffered from poor health more often than not, she still took a very active role in politics. This was in sharp contrast to the previous First Lady, Martha Washington.

She even earned the moniker “Mrs. President.” As John’s closest confidant, she was aware of the issues facing the Adams Administration but was always painting her husband in a favorable light publicly. Abigail knew that anything she said or did would be judged, as she once wrote,

“I have been so used to freedom of sentiment that I know not how to place so many guards about me, as will be indispensable, to look at every word before I utter it, and to impose a silence upon myself, when I long to talk.”

As the president’s house and capital were relocated to Washington DC in 1800, Abigail became the first First Lady to reside in the White House. While only there a short time, she found the location to be beautiful, if not a desolate and primitive wilderness. But Abigail made the best of her four months there, hosting dinners and receptions, only complaining to her family in private. By taking on these roles, Abigail’s already fragile health began to suffer. During John’s presidency, she spent a total of eighteen months between the Philadelphia presidential house and the White House in DC. The rest was spent ill in Quincy, Massachusetts.

After John lost his bid for re-election to Thomas Jefferson, the family returned to Quincy and retired to their farm at Peacefield. They were finally able to spend time together, unseparated and unaffected by public life. They lived seventeen years of quiet togetherness post-presidency before Abigail passed away from typhoid.