Considering his lack of formal education and short public service, not many expected Abraham Lincoln to reach the highest public office in the United States. Yet, his upbringing and on-the-job training throughout his meteoric rise into the national spotlight likely prepared him for the difficult presidential campaign in 1860 and the more demanding times ahead.

Humble Beginnings

American Historian James Morgan wrote in his Our Presidents (1969, p. 133), “Other Presidents than Abraham Lincoln have risen from log-cabin to the White House; other Presidents also were of humble birth; but none other has moved so humbly in his places. No honor, no power, could exalt him above his native simplicity; a common man who could walk with kings – nor lose the common touch.”

Abraham Lincoln was born on February 12, 1809, the second of two children, in a modest log cabin on the Sinking Spring Farm in Hardin County, Kentucky. His father, Thomas, a farmer and carpenter, was known for his honesty and hard work, while his mother, Nancy, was a deeply religious and compassionate woman.

In 1816, the family moved to Spencer County in southwestern Indiana, a wild and sparsely populated area that demanded hard work and resilience from settlers. By the time Abraham was 11, he had built a log cabin, farmed with his father, watched his mother die from “milk sickness” caused by drinking spoiled milk, and saw his father remarry.

Lincoln’s education was sporadic and brief, likely totaling less than one year. According to Morgan (p. 134), “Life was his school, and he was his own teacher. He swung the ax and scythe, wielded the flail, slaughtered hogs, or poled flat boats on the great rivers.”

Because the only book the Lincolns owned was the Bible, young Abe often traveled miles to borrow books from his neighbors to satisfy his curiosity. Towering over his peers in size and strength when he was 16, Lincoln had already worked as a farmhand, ferryboat rower, and grocery store clerk. When the family moved to Illinois, the 22-year-old Abraham decided to strike out on his own, settling in the small village of New Salem.

From Rail Splitter to Lawyer

Picking up where he left off in Indiana, Lincoln worked various jobs as he began to endear himself to the townsfolk of New Salem. Through the different jobs as a rail splitter, surveyor, and store clerk, Abe befriended local leaders and intellectuals who encouraged his aspirations beyond the frontier.

Historian David C. Whitney wrote in The American Presidents (2009, 11th Edition, p. 138) that Lincoln won instant popularity with the backwoods people of the community, proving “he could outwrestle the biggest bullies, could tell funnier stories than anyone, and could be depended on to help out with whenever a strong worker was needed.”

Lincoln volunteered for and fought in the Black Hawk War (1832), returning to New Salem as captain. After a failed partnership in a general store, Abe decided to improve his position through studying law. With no formal legal training available, Lincoln borrowed law books from practicing attorneys and studied alone well into the morning hours. To support himself on his quest to become a lawyer, Abraham worked as a postmaster from 1833 until 1836, when he passed his bar examination and was licensed to practice law in Illinois.

Already well-respected in his community, Abraham Lincoln, at the behest of his local supporters, ran for the state’s legislature in 1834 as a member of the new Whig Party. The political party was a unified ideological group and a coalition against President Andrew Jackson’s Democratic Party. Lincoln was attracted to the Whigs’ promotion of a more balanced power structure between the states and the federal government and the advocacy of limiting the expansion of slavery. Following his re-election in 1836, Lincoln decided to further concentrate on his flourishing legal career. He moved to Springfield, the state capital, to open a practice with his law partner, John T. Stuart.

Illinois State Politics

Lincoln flourished in Springfield, meeting and marrying the 20-year-old Mary Todd, starting a family, excelling as a lawyer, and serving four consecutive terms in the Illinois House of Representatives until 1842. Lincoln spent his early years in the state capital, making a name for himself as he traveled the Eighth Judicial Circuit, encompassing multiple counties in central Illinois. His presence at the circuit, which involved traveling from town to town to hold court sessions, allowed him to interact with a diverse clientele and build a broad network of professional relationships. The latter ensured his continued re-election to state government.

During his time in the Illinois House of Representatives, Abraham emerged as a significant figure known for his moderate stance on crucial issues. Focusing primarily on internal improvements, Lincoln strongly supported infrastructure projects that he believed would facilitate commerce and improve the quality of life for the state’s residents. Abraham also played a crucial role in shaping his state’s banking policies by supporting the establishment of a state bank and more stringent borrowing practices to stabilize the financial system rocked by the Panic of 1837, which had seen overexpansion of credit and speculation lead to the closing of banks and businesses across the nation.

It was also during this time that Lincoln became recognized for his oratory skills. The young politician was known for clear, logical, and persuasive speech, his ability to articulate complex issues straightforwardly, and his willingness for consensus-building. Already an established and respected figure in his state’s politics, the thirty-eight-year-old Abraham Lincoln sought and won the nomination and election for US Congress in 1846, becoming the state’s only Whig representative in Washington DC.

Lincoln in the US House of Representatives

Lincoln’s tenure in the US House of Representatives coincided with the Mexican-American War, which significantly impacted his tenure on Capitol Hill. As a member of the Whig Party, representing Illinois’ 7th District from March 4, 1847, to March 3, 1849, Lincoln engaged in national issues and sharpened his political acumen. Yet, his most defining and controversial action as a congressman was his vocal opposition to the ongoing conflict with Mexico.

Lincoln was very outspoken in questioning the legitimacy of the war, often challenging President James K. Polk’s justification for engaging in the conflict. In December 1847, Abraham introduced his “Spot Resolutions,” a defining moment of his time in Congress. The document demanded that President Polk specify the exact location where Mexican forces had supposedly attacked American troops, the pivotal event that had led to the conflict. Lincoln’s insinuation that the war was an unjust act of aggression aimed at expanding slavery into new territories was a direct challenge to Polk’s assertion that the attack had occurred on American soil.

By this time, the future president was already a staunch opponent of the expansion of slavery, going as far as supporting the controversial (and failed) Wilmot Proviso, a proposed amendment that sought to prohibit slavery in any territory acquired from Mexico as a result of the war. However, his anti-war views did not align with his Illinois constituents, and his focus on a broader, strong federal government instead of local concerns led to dissatisfaction within his district. Seeing the writing on the wall, Lincoln chose not to run for re-election in 1848 and returned to Springfield to resume his legal practice and continue building his political network. The freshman congressman from Illinois had bigger plans for his future.

A National Figure

Having stepped back from politics after his single Congressional term, Lincoln jumped back into the fold following the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Staying true to his convictions, Abraham was shocked at what he viewed as a moral, social, and political disaster threatening the American republic through the act’s repeal of the Missouri Compromise. The land where slavery was once Congressionally prohibited was now open to the expansion of the very institution Lincoln and the now-mostly defunct Whig Party opposed. For the Illinois attorney, this was not just about the immorality of slavery but also about the danger that the Kansas-Nebraska Act’s opening of western lands to the possibility of the “peculiar institution” posed to the free labor system and the democratic principles of the nation.

Lincoln now found himself part of a movement that quickly evolved into the formation of the Republican Party, founded on the principle of opposing the expansion of slavery into the western territories. Now firmly under the Republican banner, Lincoln toured Illinois, giving eloquent speeches and logical arguments for the new party’s platform. By the party’s first national convention in 1856, the Illinois lawyer was already a key Republican figure.

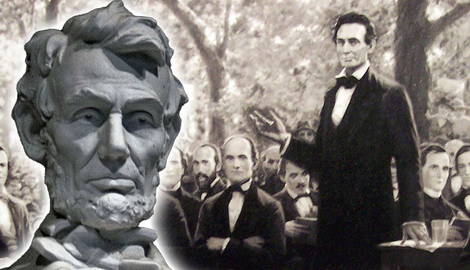

Lincoln was thrust into the national spotlight and the pinnacle of his newfound political party in 1858. With the political landscape intensely polarized across the nation, the Illinois Republican Party selected Abe to run for the US Senate against the immensely popular incumbent Democrat, Stephen A. Douglass, a national figure and the author of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. Due to the nature of the seven debates that followed between the two men attracting large crowds and capturing the entire nation’s attention, the name of Abraham Lincoln was suddenly on supporters and detractors of the new anti-slavery Republican party in every corner of the country.

Presidential Campaign

Lincoln did not win the Senate election, but the clarity of conviction of his views on slavery captured the nation’s attention. He argued that slavery was morally wrong and that its expansion threatened the ideals of the American republic, famously stating, “A house divided against itself cannot stand,” and that the nation could not remain half slave and half free.

Lincoln’s position was not to call for the immediate abolition of the institution where it already existed but to prevent its expansion into new territories. Because it was viewed by many as a moderate stance, Lincoln’s agenda appealed to a broader spectrum of voters, including those who were against slavery but not necessarily abolitionists.

Now a leading voice and the face of the Republican Party, Abraham won his party’s nomination for the President of the United States in the 1860 election at the Republican National Convention in Chicago in May 1860, securing 231.5 out of the 465 votes. The splintered Democratic Party, between those in the North advocating the allowing territories to decide the slavery issue for themselves and Southern Democrats protecting the idea of expanding slavery into new territories, nominated Stephen A. Douglass and John C. Breckinridge, respectively.

The divided opposition greatly aided Lincoln in his eventual victory in November. After concentrating entirely on winning the Northern states, with its majority of the nation’s electoral votes, Lincoln received 180 electoral votes and only 40% of the country’s popular vote, carrying all free states except New Jersey and not a single state below the Mason-Dixon Line. With the election seen by the Southern states as a direct threat to the institution of slavery and their way of life, states promptly began seceding from the Union. The real political and personal test for Abraham Lincoln’s legacy was only beginning.