In the early 1980s, gay men in the United States began falling ill with complex symptoms. Quickly, it was realized that there was no cure for the disease that many called “gay cancer,” effectively making it a death sentence. Controversially, the presidential administrations of Ronald Reagan and George Bush Sr. did little to research or combat what became known as Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome, or AIDS. The public also typically responded with homophobia and ill-informed panic to news about AIDS during the 1980s and early 1990s. Only through many years of hard work did researchers, doctors, and advocates come to win public support for the prevention and humane treatment of AIDS and its precursor, HIV (Human Immunodeficiency Virus).

Setting the Stage: Spread of AIDS to Humans

Modern researchers believe that the Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), which causes AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome), evolved from the Simian Immunodeficiency Virus (SIV) by the early 20th century. SIV has been around for thousands of years and infects primates–simians–with effects similar to HIV. Although humans became unaffected by SIV when they evolved away from primates, a mutation in SIV allowed it to infect humans once again. Researchers believe that SIV in chimpanzees and sooty magabes mutated into the viruses HIV-1 and HIV-2 that affect humans today.

The jump of HIV from chimpanzees to humans likely began near Kinshasa, Zaire (today, the Democratic Republic of the Congo), perhaps back in the 1920s. However, the first confirmed case of HIV can only be traced back to 1959. The first living patient now known to have HIV was discovered in the 1960s: a Scandinavian man who had traveled to west-central Africa. Due to the relatively long incubation period (the time when the virus builds in the body before creating symptoms) of HIV, most early cases of HIV were not detected. Up through the early 1980s, patients did not seek or receive medical treatment until HIV had already progressed to AIDS and acute symptoms appeared.

Setting the Stage: First Cases in the United States

The first confirmed cases of HIV/AIDS in the United States occurred in June 1981 among five homosexual men in Los Angeles, California. These patients presented with multiple opportunistic infections, which were linked to the collapse of their immune systems. The men, all previously healthy, died quickly of lung infections. Very quickly, other locations around the country reported clusters of infections and cancers among gay men. The first patient to be studied by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) was admitted with AIDS symptoms on June 16. He died four months later.

By July, the unknown new medical condition had been publicized in the media. Despite the disease being universally fatal, little public support for research or treatment was generated that autumn. That December, doctors reported the first infants to show symptoms similar to AIDS, with some born to mothers known to be sex workers and intravenous drug users. Later that month, a nurse in Kansas went public with his condition and described the symptoms to encourage others who might experience the same symptoms to seek treatment.

Early 1980s: AIDS Epidemic Begins

In 1982, public awareness of AIDS spread rapidly, with the first member of Congress (US Representative Henry Waxman) holding a hearing in April. At the time, AIDS had no universal name and was frequently known as “gay cancer,” with the acronym GRID (Gay-Related Immune Deficiency) being used by the New York Times. Unfortunately, this created misconceptions that the disease only affected gay men and increased homophobia. In July of that year, the CDC reported the first cases of AIDS in hemophilia patients who had received blood transfusions.

Two months after the first hemophiliacs were discovered to have the disease, the acronym AIDS was used. Early efforts in Congress to dedicate funds to studying the new disease failed at first, though they eventually succeeded in July 1983. The realization that AIDS could be transferred through blood transfusions raised concerns about the safety of America’s blood supply in early 1983, though scientific consensus about how to achieve this was slow. In May, the first gathering of AIDS patients occurred, providing a human face to the disease and urging compassion. Tensions grew between the gay community and the government, with many gay men upset at the lack of government action in studying AIDS.

AIDS Epidemic & the Reagan Administration

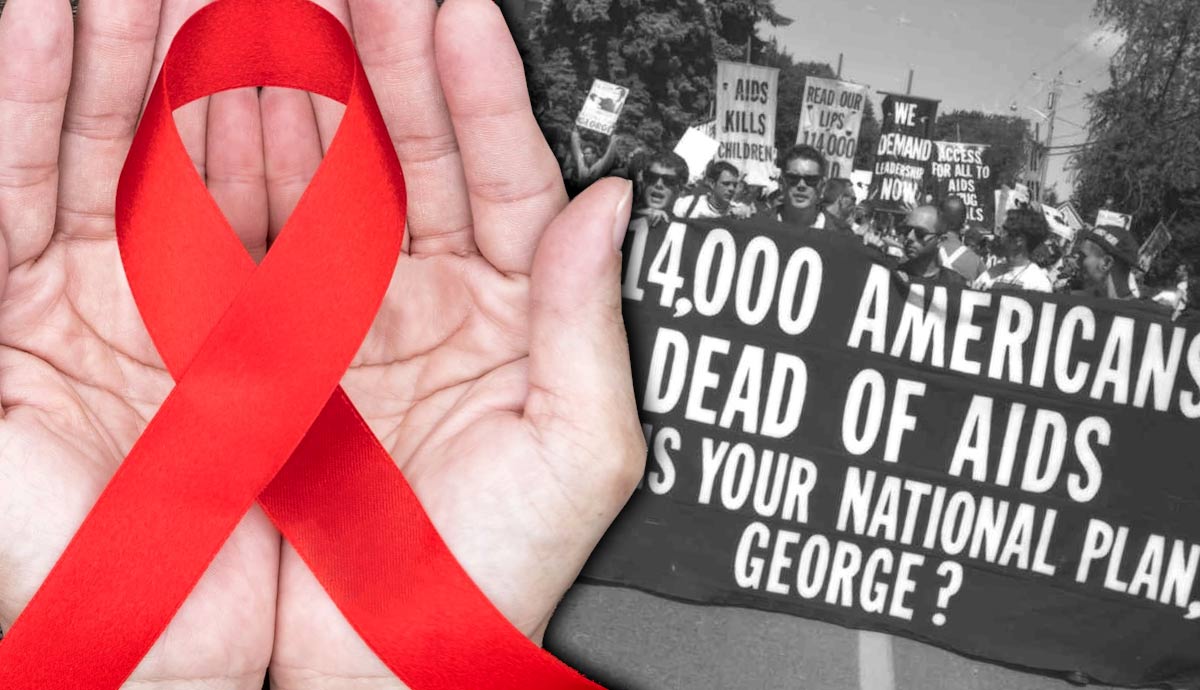

Despite the rapid lethality of AIDS and lack of comprehensive treatments, the administration of US President Ronald Reagan was frequently criticized by activists for appearing unconcerned with the growing epidemic. The epidemic brought increased media attention to America’s gay community, resulting in both compassion and public disdain. Despite the CDC publicly ruling out the possibility of the AIDS virus – tentatively reported in May 1983 by French researchers – being transmitted through casual contact, there was widespread public fear of anyone who might exhibit AIDS-like symptoms.

Controversially, the conservative Reagan administration remained largely silent on the growing epidemic and suggested that the gay lifestyle was a contributing factor. Critics felt that Reagan was ignoring the disease to retain the support of the “religious right,” or conservative Protestants who had been a key supporting bloc during his 1980 presidential campaign. The president himself did not directly address AIDS until 1985, four years after it began taking lives. Reagan’s belated addressing of the issue, coming months after the CDC’s first national AIDS plan was refused by his administration, may have been influenced by Reagan’s old Hollywood friend, actor Rock Hudson, being infected with AIDS. Hudson died shortly after Reagan finally addressed the disease in a press conference.

AIDS Epidemic & the Bush Sr. Administration

In 1988, Reagan’s vice president, George Bush Sr., won the presidential election and replaced his boss as chief executive a few months later. Bush’s AIDS response was not significantly different from his predecessor, although Bush was less adherent to the religious right than Reagan. Due to the lack of available treatments for HIV/AIDS, the number of AIDS deaths continued to rise steadily during the Bush administration, exceeding 32,000 annually by 1992. Bush sparked controversy during his re-election bid when he complained that “extremes are hurting the AIDS cause” and implied that personal behavior was a driving factor behind catching HIV in a June 1992 debate with Democratic rival Bill Clinton and independent candidate Ross Perot.

However, more progress was made in the fight against AIDS during the Bush administration, with both the president and AIDS and gay rights advocates claiming credit. In 1990, President Bush urged Congress to include protections for those with HIV and AIDS under the Americans With Disabilities Act (ADA). Although Bush signed the ADA Act of 1990 and enacted legal protections for HIV/AIDS patients, his administration controversially retained a block on HIV-positive individuals from entering the United States. Observers after Bush’s death in 2018 characterized his administration’s AIDS response as less conservative than Reagan’s but similarly devoid of top-down leadership and socially opposed to LGBTQ rights.

1989: Ryan White Story Humanizes AIDS

One AIDS victim referenced in the 1992 presidential debates was teenager Ryan White. White was a hemophiliac who contracted HIV during a December 1984 blood transfusion. Despite having contracted HIV, White tried to return to school and live a normal life. The local community, however, responded with anger and fear, erroneously believing that White could infect other students. White and his family fought for his right to attend school and educate the public on the facts relating to HIV. On January 19, 1989, ABC aired The Ryan White Story, a documentary detailing the Whites’ struggle to have Ryan return to school.

The story generated national attention and is famous for humanizing those who have HIV and AIDS, as well as receiving high-profile praise from celebrities and politicians (including former president Ronald Reagan). Ryan White passed away in April 1990, having lived five years longer than doctors initially predicted. Four months later, Congress passed the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (Ryan White CAREs) Act, which provided grant funding for AIDS care and relief programs. The Act has been continuously renewed and provided billions of dollars in grants since 1991.

AIDS During the Clinton Era

Upon taking office in 1993, Democratic president Bill Clinton was more active in speaking about AIDS than either Republican predecessor. By the early 1990s, AIDS had become a leading cause of death for Americans between ages 25 and 44, underscoring its definition as an epidemic. Clinton created a position of national AIDS Policy Coordinator to streamline federal efforts at HIV/AIDS research and provide assistance to state and local organizations that dealt with the disease. As a Democrat, Clinton was more supportive of LGBTQ rights than his two predecessors, though many argue in retrospect that he did not go far enough to resist discrimination against LGBTQ citizens, such as through the creation of the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy toward homosexuals in the military as opposed to ending the military’s ban on openly homosexual members.

Although Clinton was a stronger advocate for AIDS research and treatment funding than Reagan or Bush, there are many who are still critical of his decisions. Some argue that Clinton did not follow through on campaign promises to create a “Manhattan Project” for seeking a cure for HIV. Clinton also allowed the detention of HIV-positive Haitian refugees at the US military installation at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, instead of allowing them into the country. Another point of contention was that, unlike some other Western nations, the Clinton administration did not adopt a sterilized needle distribution and exchange program to limit the spread of HIV through intravenous drug use.

HIV and AIDS Treatments Improved During the 1990s

While the Clinton administration received some criticism from AIDS advocates, particularly in retrospect, the Clinton era saw a tremendous increase in the ability to treat HIV and AIDS. The mid-1990s saw the release of home-testing kits for HIV, allowing HIV-positive individuals to discover their status and limit any behavior that could spread the virus. In 1996, the number of new AIDS cases declined for the first time since the epidemic began in 1981. By the following year, the number of AIDS deaths had been cut by almost half thanks to new anti-viral treatments.

The early 1990s saw increased FDA approval of more NRTI (nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor) medications, adding to the number of treatment programs for those with HIV and AIDS. The adoption of new treatments by the FDA was a huge relief; there was no FDA-approved AIDS treatment prior to 1987, and many AIDS patients had to seek black-market remedies or smuggle medications from other countries. The popular 2013 film Dallas Buyers Club dramatized the real-life story of Ron Woodruff, who smuggled AIDS treatments into the US from Mexico during the late 1980s.

Modern Era: HIV as a Chronic Condition

By the 2010s, HIV treatments had become so successful that HIV became considered a chronic condition rather than an automatic precursor to AIDS. Improvements in testing for HIV, public awareness of safe sex protocols, and the growth and expansion of medical treatments for HIV have all slowed the spread of the disease. Modern treatments known as HAART (highly active antiretroviral therapy) have been able to reduce the level of HIV in the body and prevent it from developing into AIDS.

HAART must be taken daily for the rest of the patient’s life, as it does not eliminate HIV entirely. Today, that treatment has been consolidated into a single pill, allowing for greater ease of treatment and patient self-care. Previously, treatment for HIV was complex and rigorous, sometimes overwhelming patients who might miss doses of crucial medications. Since the late 1990s, new HIV cases have fallen significantly in the United States, limiting shortages of medication. The Affordable Care Act passed in 2009, prevents health insurance companies from denying coverage to new patients with HIV as a pre-existing condition.

HIV/AIDS Today: Hopes for a Cure

Fortunately, the automatic progression of HIV into AIDS has been halted by modern science. Still, there may be long-term side effects of HIV treatments, such as increased susceptibility to age-related conditions like cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis. As with all chronic conditions, patients and advocates hope for a cure. Currently, no cure for HIV exists. However, a handful of patients have allegedly been cured of HIV due to stem cell treatments for cancer.

The stem cell treatment, unfortunately, is only currently available under specific conditions and will not likely provide the HIV-fighting function in most patients. Fortunately, scientific research continues toward a cure that could benefit all HIV patients. As of early 2023, primate test subjects cured of HIV using stem cell treatment had remained virus-free for four years. Hopefully, human trials will begin soon and eventually lead to FDA approval of a stem cell treatment that can be used by all those infected with HIV.