Famous for its unique large-size statues, the settlement of ‘Ain Ghazal lies on the outskirts of Jordan’s capital, Amman. It’s also famous for being one of the oldest places of human settlement, predating the ancient empire of Sumeria, Egypt, and Greece by many thousands of years.

Thus, ‘Ain Ghazal is considered an extremely precious place and an invaluable piece of the puzzle of prehistoric human development.

Archeology in ‘Ain Ghazal

The site of ‘Ain Ghazal was discovered in 1974 by developers who were building a road to link Amman to the neighboring city of Zarqa. Knowing they had found something important, the site was protected and earmarked for later excavation. It took six years, however, for excavation work to begin. Unfortunately, by the time the site was discovered, several hundred yards of road had already jutted into the site, and the damage this caused is unknown. Nevertheless, the site revealed a wealth of discoveries that astounded the archeological world.

Under the direction of American archeologist Gary O. Rollefson, who had worked extensively in Israel and Jordan, the site of ‘Ain Ghazal began to be excavated in 1982. Over six seasons through the 1980s, Gary Rollefson and his team uncovered finds unique to ‘Ain Ghazal, creating an image of the culture that existed.

Rollefson was joined by Jordanian archeologist Zeidan Abdel-Kafi Kafafi, and in the early 1990s, their team continued the work.

Rather than being free to focus the research in a specific area, much of the archeology that was done was essentially a rescue mission to make discoveries in order to save the site from urban encroachment. Since 2004, the site has been under the protection of the World Monuments Fund and its flagship program, World Monuments Watch, which is designed to safeguard archeological sites around the world.

Periods of Settlement

Human habitation of ‘Ain Ghazal is split (academically) into four periods, identifiable by the changes in culture and practice evident by those who lived at the site. Habitation occurred for about 2,000 years, starting around 7250 BCE with the Middle Pre-Pottery Neolithic B period, which ended around 6500 BCE.

This was followed by the Late Pre-Pottery Neolithic B, which lasted until 6000 BCE. The Pre-Pottery Neolithic C lasted from 6000 BCE to 5500 BCE, and lastly, the Yarmoukian Pottery Neolithic period occurred from 5500 BCE to 5000 BCE.

At its peak around 7000 BCE, ‘Ain Ghazal was populated by approximately 3,000 people, four to five times the number of inhabitants in the contemporary settlement of Jericho 32 miles (52 kilometers) away.

Building & Maintaining the Settlement

The location of ‘Ain Ghazal 9,000 years ago was practical for a number of reasons. The most important immediate need for any settlement is a source of fresh water, and this was supplied by the Zarqa River. It sat on a significant elevation, offering a view of the surrounding area, which lies where two ecosystems meet. To the west of the settlement was woodland, and to the east was an open steppe desert. This offered a seemingly perfect opportunity to hunt and farm.

This, however, wasn’t as perfect as it seemed. Throughout the ages, the desert and the forest zones would move back and forth, leaving the people of ‘Ain Ghazal with the need to constantly adapt.

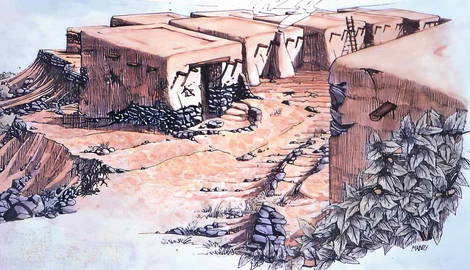

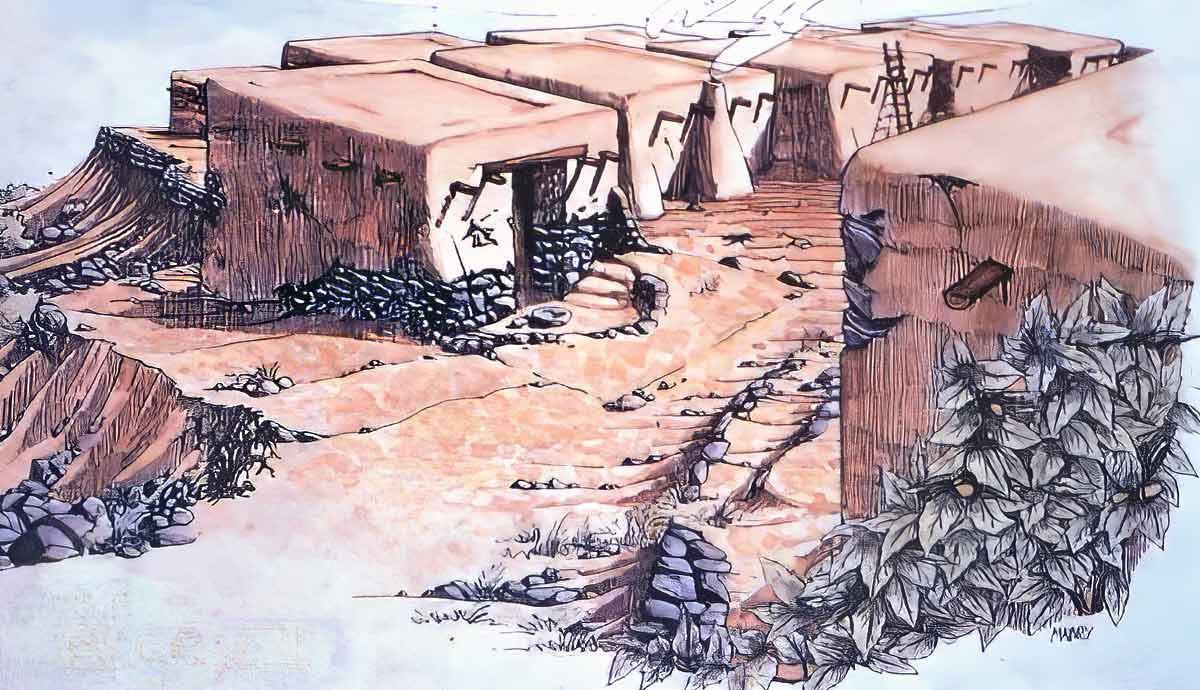

Construction was performed in a style consistent with Levantine Natufian culture seen throughout the area at the time. Mudbrick houses were built to accommodate a main room and a small anteroom. Mud covered the exterior, while the interior was covered in lime plaster. Every few years, the walls were replastered.

Lifestyle & Culture

The people of ‘Ain Ghazal had a varied diet that included the food provided by both hunting and farming. The forests and semi-arid plains provided a wealth of animals such as gazelle, deer, horses, pigs, foxes, and hares. Attempts were also made to domesticate sheep and goats. In addition to game, crops such as wheat, barley, peas, chickpeas, beans, and lentils were also grown. The diet was also supplemented by wild plants.

Neolithic ‘Ain Ghazal represented a huge leap in the success of human civilization and the coming together of people from various regions. ‘Ain Ghazal was fairly large compared to its contemporaries, and with vast tracts of arable land, many people from failing settlements nearby migrated to ‘Ain Ghazal. DNA tests have shown that the population of ‘Ain Ghazal was made up of at least two distinct groups of people from the Natufian culture in the Levant, as well as another group of people who migrated to the settlement from the east in what is today Iraq.

Like many other archeological sites that date back to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic in the Levant, ‘Ain Ghazal’s burial practices show marked similarities to their neighbors in the region. Bodies were buried in a flexed position, usually under the floors of houses. After significant decomposition, the skulls, usually just the cranium, were removed. The mandible was often left behind. It is assumed the cranium was used in rituals involving some sort of religious practice of ancestor worship. Plaster was used to recreate the faces in the same way they were done in various other Natufian sites.

There is also evidence that a class system emerged as immigrants became part of the population of ‘Ain Ghazal. Many bodies were unceremoniously discarded on trash heaps, and it is likely these were the bodies of lower-class individuals, probably newer immigrants.

Of particular note regarding the culture of ‘Ain Ghazal is the prevalence of ceramic figurines. Both animals and people were created using clay. Some of the figurines of horned animals were pierced in their vital parts and buried in the houses, while some were thrown into fires. All of this suggests a strong connection to a religion involving the spirits of animals.

Large human figures were also found, some of which were housed in ritual buildings specifically designed for the purpose of housing the artifact.

Although most of the figurines are of animals, ‘Ain Ghazal is most well known for its set of human figurines, some of which stand approximately 2 to 3 feet tall. They were made by molding plaster over a core of bundled twigs used as an armature, and they were decorated with cowrie shells for eyes. Instead of bundled twigs, some statues were molded around braided rope. Many of the statuettes were also painted to show clothing, hair, and ornamental tattoos. In total, 15 full figurines and 15 busts have been found. Three of these busts had two heads, and it is images of these that are particularly common in modern imaginings of ‘Ain Ghazal.

Most of these statues were found buried in an east-west position and were remarkably well preserved. For the most part, genitalia are absent on the statues, with only a few of the oldest having the feature. Breasts are displayed on some of the older statues, and the bodies are well-proportioned with regard to the head. The eyes, however, are oversized in all the artifacts. The outlines of the eyes were painted black with bitumen, which was a rare and precious substance found nearby around the Dead Sea.

The statues exhibit a recessed feature in the forehead, presumably for attaching hair or a headpiece as decoration. The older statues tend to be more individualistic, while the later statues, including the two-headed busts, seem to follow a standardized style. It is possible that the earlier statues represented specific individuals, while the later statues were designed to represent anybody.

‘Ain Ghazal is an extremely important site. For its time, it was a large city, and like many of its contemporaries such as Çatalhöyük, Jericho, and other Natufian sites, ‘Ain Ghazal represents a transition from a hunter-gatherer way of life to a more sedentary one through the Neolithic Revolution which saw the rise of agriculture as a driving force behind the beginnings of civilization.

An important dynamic that existed in ‘Ain Ghazal which is diminished in other, smaller settlements, is the evolution of a stratified society, with an elite, ruling class. It is plausible that immigrants were seen as an unnecessary burden on society, and were treated very differently to those who already lived in ‘Ain Ghazal. In this, we see a societal dynamic still represented in human society today.