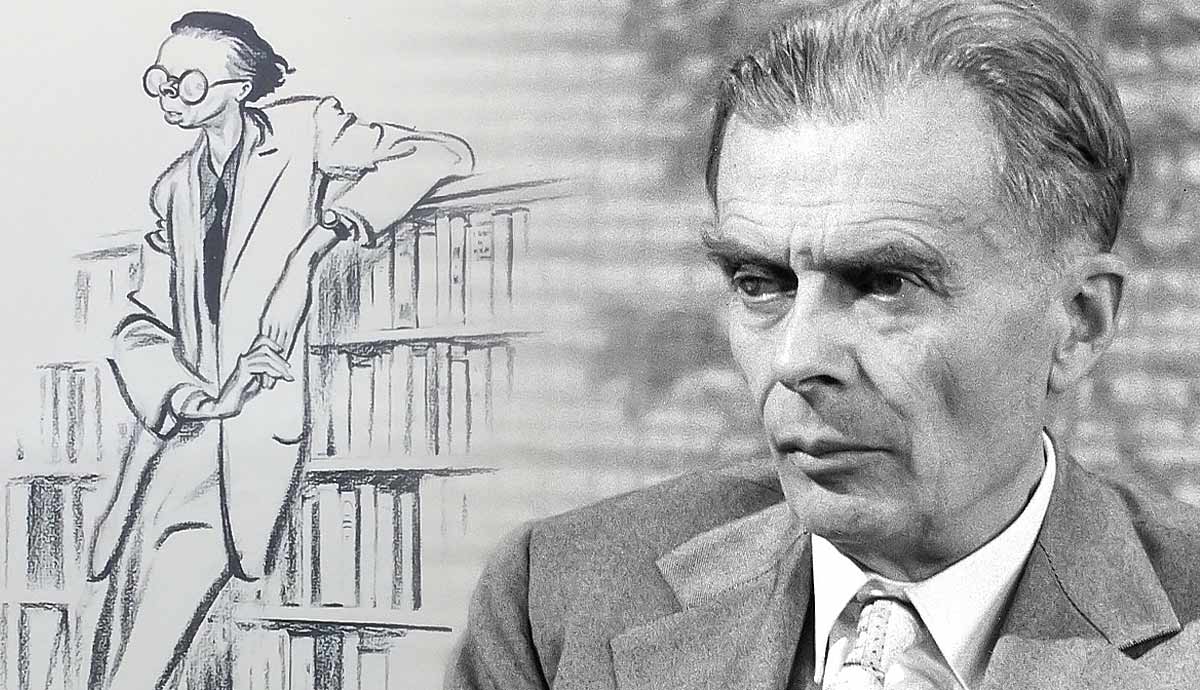

When Aldous Huxley passed away in 1963, his death was relatively little commented upon, coinciding as it did with the rather more shocking assassination of John F. Kennedy. Yet his death marked the loss, nonetheless, of one of the twentieth century’s most important writers and thinkers. He was deeply committed to pacifism, universalism, and mysticism, all of which shine through in his writing – be it fiction or non-fiction – and informed the way he lived his life, from refusing to bear arms when applying for US citizenship to using his substantial earnings as a screenwriter to fund the transportation costs of those fleeing Nazi Germany. Here, we will take a closer look at the life of the man behind Brave New World…

Early Life: Family Background, Bereavement, & Education

Born on July 26, 1894 near Godalming, Surrey, Aldous Leonard Huxley belonged to a family distinguished in both science and the world of letters. His father was Leonard Huxley, schoolmaster, writer, and editor of The Cornhill Magazine, who in turn was the son of Thomas Henry Huxley, a prominent zoologist often referred to as “Darwin’s bulldog.” His older brother, Julian, and half-brother, Andrew, would, in turn, follow in their grandfather’s footsteps, going on to enjoy celebrated careers in biology.

Additionally, Aldous Huxley’s mother, Julia Arnold, was the niece of the poet and cultural critic Matthew Arnold, and the sister of the novelist Mrs. Humphry Ward, after one of whose fictional characters Julia named her second son.

Aldous Huxley, then, was always expected to distinguish himself in one intellectual field or another. His parents were both involved in the early stages of his education, which began in his father’s botanical laboratory. He then attended Hillside School near the family home in Godalming, where he was taught by his mother before she became terminally ill with cancer.

Huxley’s mother died in 1908, by which time he had been sent to the elite Eton College. This formative loss – as well as his father’s later remarriage – inspired some of the events depicted in Huxley’s 1936 novel Eyeless in Gaza. While at Eton, he contracted keratitis in 1911, which left him with radically impaired vision for many years and effectively ended his hopes of pursuing a career in medicine.

Instead, in 1913, Huxley matriculated at Balliol College, Oxford University, to study English Literature – just as his mother had before him at Somerville College. He edited Oxford Poetry during his final year and graduated in 1916 with a first-class degree. In the same year, he published his first collection of poetry, The Burning Wheel.

Finding His Feet as a Writer

From 1917 to 1918, Huxley returned to Eton to teach English and French. While he struggled to maintain discipline in the classroom, among his students was a young Eric Blair, who would go on to be better known as George Orwell and who remembered his former teacher and fellow writer as having an admirable vocabulary. At the same time, Huxley published two further poetry collections: Jonah (1917) and The Defeat of Youth and Other Poems (1918).

While Huxley did not have great success upon his return to Eton, at the time of his graduation, jobs were scarce as Britain was still fighting the First World War. Having volunteered for the British Army and been rejected on account of his eyesight (his bout of keratitis left him partially sighted in one eye), he spent much of his time at Garsington Manor, the home of Lady Ottoline Morrel, near Oxford, where he was employed as a farm laborer. Ottoline invited many artists, writers, and intellectuals to Garsington, including members of the Bloomsbury Group, some of whom Huxley met. He would later satirize the Garsington milieu in his 1921 debut novel, Crome Yellow.

While at Garsington, however, he also met Belgian refugee and epidemiologist Maria Nys. After being offered a job at the Athenaeum under John Middleton Murry in 1919, Huxley and Nys married. A year later, Huxley published his first collection of short stories, Limbo (1920), which was soon followed by his debut novel, Crome Yellow. He continued to publish works throughout the 1920s, including the novels Antic Hay (1923), Those Barren Leaves (1925), and Point Counter Point (1928). In addition, he wrote for Vanity Fair and British Vogue.

1930s and 40s: The Golden Years & Moving to the United States

Huxley’s best-known works, however, were largely written in the 1930s. Brave New World, for example, was published in 1932. It was also during the 1930s that Huxley wrote what is now widely considered his most accomplished – if not most widely read – novel, Eyeless in Gaza (1936). Having been introduced to Gerald Heard in 1929, Huxley became increasingly committed to pacifism, which is reflected in many of his 1930s works, including Eyeless in Gaza, in which the aimless Anthony Beavis is converted to pacifism by Dr. James Miller. Huxley himself was actively involved in the Peace Pledge Union and edited An Encyclopedia of Pacifism.

Within its meditations on pacifism, Eyeless in Gaza also predicts the outbreak of another war. By the time World War II was declared in 1939, however, Huxley and his wife were living in the United States, having relocated in 1937 (the same year that Huxley’s pacifist essay collection, Ends and Means, was published) with his wife, son, and friend Gerald Heard, on account of Nys’ ill health.

Moving to the United States also gave Huxley access to highly lucrative screenwriting opportunities. According to friend and fellow writer Christopher Isherwood, Huxley earned more than $3,000 per week (an even more princely sum back in the 1930s) as a screenwriter for such film adaptations as Pride and Prejudice (1940) and Jane Eyre (1944).

Famously, in 1945, Huxley was commissioned by Walt Disney to write a script adapting Alice’s Adventure in Wonderland for the screen, which was never used as Disney claimed only to be able to understand every third word. It should also be noted that Isherwood also claimed, however, that Huxley used the majority of his screenwriting riches to fund the transportation of Jewish and left-wing refugees from Nazi Germany to safety in the United States.

World War II & Huxley’s Later Years

While Huxley only wrote two further novels – The Genius and the Goddess (1955) and Island (1962) – in the 1950s and 60s, his output of non-fiction works was prolific. Among his most famous was The Doors of Perception, published in 1954, which went on to become a foundational text for the counter-cultural revolution of the 1960s. In The Doors of Perception, he recounted his first experience taking the psychedelic drug Mescaline and, in so doing, would inspire Jim Morrison to name his band The Doors.

One year before the publication of The Doors of Perception, however, Huxley and his wife had applied for US citizenship. As a pacifist, Huxley stated his refusal to bear arms for the United States but did not specify that his objection was on religious grounds (the only reason, under the McCarran Act, that was deemed acceptable for the refusal to bear arms). Having reached this stalemate, the judge had no alternative but to adjourn the application, which Huxley, in turn, withdrew. Despite not having US citizenship, Huxley, Maria, and their son Matthew remained in the US, where Maria died of cancer just two years later, in 1955.

One year after Maria’s death, Huxley married a second time, taking Laura Archera, an American writer, psychotherapist, and violinist, as his wife. Laura went on to write a biography of her husband, titled This Timeless Moment and worked tirelessly to keep his literary legacy alive.

Their marriage, however, was relatively short-lived. In 1960, Huxley was diagnosed with laryngeal cancer. Nonetheless, he continued to work, delivering lectures at the UCSF Medical Center and the Esalen Institute that would inspire the Human Potential Movement. As well as this, he wrote his final novel, Island, in 1962 as well as what is perhaps his seminal work of non-fiction, Literature and Science, in 1963.

However, just two months after the publication of Literature and Science, Aldous Huxley died on 22nd November 1963, aged 69. Like fellow writer C. S. Lewis, news coverage of his death was overshadowed by the shocking assassination of President John F. Kennedy, who was shot a mere seven hours before Huxley himself passed away.

The timing of Huxley’s death not only meant that it was overshadowed by that of John F. Kennedy but also that he did not live to see the full effects of the 1960s counterculture his work had, in part, helped to inspire. Nonetheless, his was a life of principle and productivity, the legacy of which lives on to this day.