During his reign, Philip II of Macedon (382-336 BCE) transformed Macedonia from a weak backwater state into the most powerful military and political force in the Greek world. This brought him into conflict with Thebes, which was the previous hegemonic power in Greece. A brutal Macedonian victory at the battle of Chaeronea 338 BCE, broke Theban power and led to the city being garrisoned by Macedonian troops. However, Philip was unable to enjoy the fruits of his victory for long as he was assassinated in 336 BCE. Macedon’s vassals seized the opportunity to revolt, forcing Alexander the Great to embark on an arduous campaign against them. Leading up to the Battle of Thebes, the time to drive out the hated Macedonians appeared to be at hand.

Before the Battle of Thebes: The Balkan Revolt

News of Philip’s death caused many of Macedon’s erstwhile vassals and allies to revolt. During his reign, Philip had made himself the hegemon of Greece and much of the Balkans through numerous military campaigns. With his death, many city-states, tribes, and kingdoms saw an opportunity to reclaim their former independence.

To make matters worse for the Macedonians, prior to his death, Philip had already dispatched a sizable force to Anatolia led by some of his most experienced generals. However, Alexander was not one to give into despair and he immediately sprung into action. With a picked force of 3,000 cavalrymen, he rode south through Thessaly and Greece as far as Corinth. This show of force overwhelmed the Greeks, and they agreed to return to the Macedonian fold.

In the north, the situation was potentially more dangerous. The Thracian and Illyrian tribes, traditional enemies of Macedon, saw Philip’s death as an opportunity to invade. The northern regions were a source of great wealth and manpower for Macedon, as well as being critical to the safety of the kingdom. As such, in the spring of 335 BCE, Alexander marched north with his army into the Balkans.

The fighting was difficult, but Alexander led the Macedonians to victory after victory. However, news of Alexander’s progress was slow to reach the Greeks in the south. When it did come, it was distorted, leading them to believe that Alexander had died of the wounds he received at the siege of Pelium. This news was the spark that set in motion the battle of Thebes.

Athenian Antagonisms

One of the most dedicated opponents of Philip and Alexander was Demosthenes of Athens (384-322 BCE). A skilled orator and statesman, he spent his career urging opposition and resistance to Macedon. His goal, however, was to replace Macedonian hegemony with Athenian hegemony.

To further his goals, Demosthenes presented a man to the Athenian assembly who claimed to have witnessed Alexander’s death at Pelium. Demosthenes’ efforts were aided in part by Darius III, king of Persia. In order to forestall Alexander’s invasion of Anatolia, he had been distributing large sums of money to any Greek state willing to resist the Macedonians. These machinations were enough to convince a band of Theban exiles in Athens to return home and lead an uprising against the city’s Macedonian garrison.

The Thebans received a large sum of Achaemenid money to aid them in their efforts. Then as now, war was an expensive undertaking. Demosthenes also received a large payment from the grateful Achaemenids. However, rather than pocketing it for himself he used it to purchase weapons and supplies which he gave to the Thebans to aid them in their fight. He also used his considerable political influence to convince his fellow Athenians to sign up to a defensive alliance with Thebes that was aimed at the Macedonians.

It should be noted that Athens, Thebes, and Persia were not particularly fond of each other, and that they were, more often than not, bitter rivals. Their support of each other in this instance, had less to do with any newfound affection and more to do with the cold calculation that they could use each other against the hated Macedonians.

Thebes Revolts

With this support the Thebans declared their independence and killed a pair of Macedonian officers who had been roaming about the city. However, they failed to eject the Macedonian garrison at large from the Cadmaea, the citadel at the center of the city. Having failed to take the Cadmaea, the Thebans set up a blockade.

Along with the Theban uprising, other cities in Greece renounced their allegiance to Macedon. In Athens, Demosthenes again denounced Macedon and voted for more weapons and supplies to be sent to the Athenians. The Athenians, however, refrained from sending any troops to Thebes, preferring to await further developments. The Spartans, long hostile to the Macedonians, marched their army to the isthmus of Corinth and then encamped. They would not leave the Peloponnese despite their hatred of the Macedonians.

Despite their hatred of the Macedonian hegemony over Greece, none of the Greek city-states were willing to commit themselves fully to supporting Thebes. Nor had the Thebans yet succeeded in completely retaking their city from the Macedonians. The start of the revolt had so far met with mixed if not disappointing results. There was still hope, however, as more and more city-states positioned themselves to support the Thebans. Moreover, the Macedonian garrison in the Cadmaea was not expecting trouble and had, therefore, not prepared for a siege. It was only a matter of time before they would be forced to surrender. Should that happen, support from the other Greek city-states, especially Athens and Sparta, was likely to increase.

Alexander Marches on Thebes

Alexander, was of course at this point still very much alive and well. When he learned of the events at Thebes, he became greatly concerned. At the beginning of his reign, he had secured Greece through a show of military force. Now, there was no comparable Macedonian army on the ground in Greece. Moreover, there was a real chance that more and more Greek city-states would rally to the Theban cause. With his characteristic decisiveness, Alexander raced south with his army. Time and speed were of the essence if Alexander was to contain the situation.

Alexander and his Macedonians set a blistering pace. After seven days of marching, they reached Thessaly, and before long they were outside the territory of Thebes. The Macedonians had marched over 300 miles in just under two weeks’ time. It was an astonishing speed for armies of the period. The Macedonians moved so fast that they had not even been detected when they passed through the pass at Thermopylae.

So quickly had the Macedonians arrived that at first, the Thebans refused to believe that it was Alexander at the head of the army. At first, they believed that it must be the Macedonian general Antipater, whose smaller army was in Macedonia. Yet it soon became apparent to all that it was indeed Alexander who had arrived. With Alexander’s arrival, the tide began to shift against the Thebans. Many smaller city-states began to abandon the Thebans and offer their allegiance to Alexander.

The Siege of Thebes

Alexander offered the Thebans extraordinarily lenient terms given the situation; all he demanded was the two ringleaders of the revolt. Despite having been abandoned by their allies, the Theban council enthusiastically voted for war. They, in turn, demanded Alexander hand over two of his generals to them. The Macedonian garrison was still ensconced in the Cadmaea, the citadel of Thebes, which was surrounded by siege works. The Thebans had also surrounded the exterior of the city in a palisade which, if stoutly defended, would make any attack difficult. Rather than immediately attacking, Alexander rested and prepared his army for three days, giving his men additional time to recover from their march.

In preparation for the imminent Macedonian assault, the Thebans freed their slaves and placed them under arms to defend the city. They drew up their infantry and cavalry within the palisades and placed their women and children on the walls and in the temples.

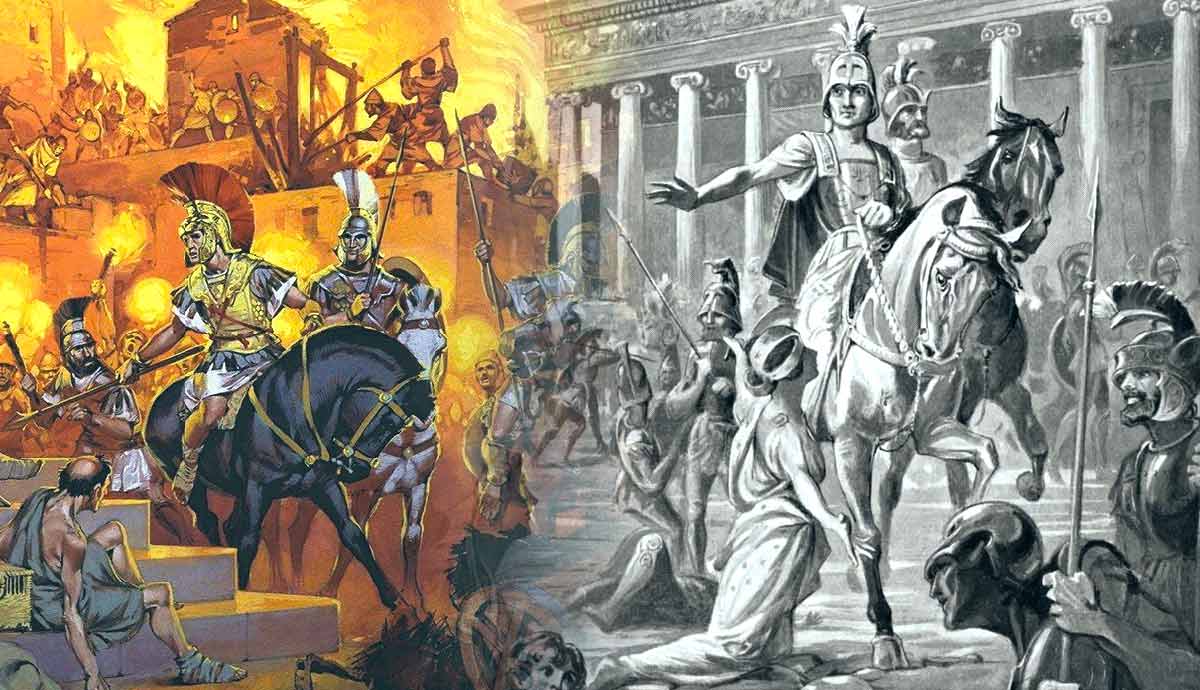

Alexander divided his army into three columns. The first column assaulted the palisades but began to lose momentum after breaking through. They were relieved by the second column which pushed through and drove the Thebans into the city before being briefly repulsed. It was at this point that Alexander brought forward the rest of the troops. With the Thebans in retreat the Macedonian garrison came out of the Cadmaea, which effectively ended any organized Theban resistance.

Thebes Laid Waste

With the city now at his mercy, Alexander was not inclined to treat the Thebans with mercy. Alexander’s troops, especially his allied Greeks, slaughtered the Thebans wherever they could lay hands on them. Attempts to surrender were ignored, and neither women nor children were spared. The extent of the slaughter was such that it horrified the contemporary Greeks. Once the Macedonians and their allies had sated their thirst for blood, they turned their attention to the city itself, and the surviving Thebans. Alexander wanted to send a message to the Greeks, in order to deter any future thoughts of rebellion.

All the survivors—men, women, and children—were enslaved. While some 6,000 were killed in the fighting and subsequent slaughter, it is estimated that around 30,000 were afterward enslaved. Only the priests, priestesses, and guest friends of Philip and Alexander were spared this fate. All of Thebes’ territory (which consisted of some of the best lands in central Greece) was then broken up and distributed to Macedon’s Greek allies.

All of the buildings in the city were razed to the ground, with a few exceptions. The pious or superstitious Greeks spared the temples, along with the strategically important Cadmaea, and Alexander himself spared the home of the famed poet Pindar (b.518 BCE).

Aftermath

The sudden revolt, fall, and destruction of Thebes sent shockwaves across the Greek world. Those who revolted or had otherwise shown support to the Thebans now quickly moved to reconcile with Alexander and offer their allegiance. Many executed the leaders of the anti-Macedonian factions within their own cities.

The only remaining matter for Alexander at this point was Athens and Demosthenes. At first, Alexander demanded that Demosthenes and his supporters be handed over for punishment. But the Athenians were reluctant to accede to, despite the risk. Eventually, Alexander allowed himself to be persuaded to accept more lenient terms and only exiled one of the Athenian ringleaders. Demosthenes would, in fact, outlive Alexander.

Alexander the Great’s capture and destruction of Thebes won him the acquiescence and fear of the Greeks, but not their love and support. It did prevent most city-states from considering rebellion when he embarked on his long campaign against the Achaemenid Empire. Without having to worry about a threat to his rear, or his long supply lines or communications with Macedon, Alexander could focus his full attention on his conquests. Thebes never fully recovered from its destruction at the hands of Alexander. In 315 BCE the city was re-founded with the help of other Greek city-states, including Athens, which rebuilt its walls.