Alice Neel is one of the most celebrated portrait painters of the twentieth century, one who presented a rich and complex view of identity as seen from a female gaze. She emerged out of New York at a time when art history was still dominated by men, and women were still idealized or objectified as sirens, goddesses, muses, and sex symbols. Alice Neel upturned these conventions with her frank, fresh, and sometimes brutally honest portrayals of the real people, including women, men, couples, children, and families from a wealth of different backgrounds, who all lived around her in New York City. Taboo subjects in Neel’s art, including pregnant women, nude men, or eccentric and marginalized figures, challenged viewers to see the real world in all its multifaceted, intricately complicated glory. In all her portraits, Alice Neel invested great dignity and humanity, and it is this depth of emotion in her art that has made Neel such an influential pioneer of the female gaze.

The Early Years: Alice Neel’s Childhood

Alice Neel was born in Philadelphia in 1900 to a large family of five children. Her father was an accountant for the Pennsylvania Railroad who came from a large family of opera singers while her mother descended from the signatories who made the Declaration of Independence. In 1918, Neel trained with the Civil Service and became an army secretary to earn money to help support her large family. On the side, she continued to pursue a burgeoning passion for art with evening classes at Philadelphia’s School of Industrial Art. Alice Neel’s mother was less than supportive of her daughter’s ambitions to be an artist, telling her, “You’re only a girl.” Despite her mother’s judgments, Neel was undeterred, earning a scholarship to study at the Fine Arts program in the Philadelphia School of Design for Women in 1921. She was an outstanding student who scooped up a series of awards for her striking portraits, and they would become the focus of her art for the rest of her career.

Early Struggles

After moving between Cuba and the United States, Alice Neel and her boyfriend, the Cuban artist Carlos Enriquez, settled in the Upper West Side of Manhattan, where their daughter Isabetta was born in 1928. In 1930, Enriquez left Neel, taking their daughter with him to Havana, where she was placed in the care of his two sisters. Neel was left penniless and bereft, moving back to her parent’s house in Pennsylvania, where she suffered a complete mental breakdown. Neel continued to paint obsessively throughout this horrific ordeal as an outlet for her pain, working in a shared studio with her two college friends Ethel Ashton and Rhoda Meyers.

Some of Neel’s most celebrated early paintings came from this dark period, including a series of nude portraits documenting Ashton and Meyers in strange, haunting lighting and unusual viewpoints that challenged stereotypical portrayals of women by looking at them with a female gaze. In the strangely angled and eerily lit Ethel Ashton, 1930, Neel invokes a quiet sense of discomfort and unease, as the model self-consciously looks up at us as if aware she is being scrutinized and objectified by a viewing audience. Neel also highlights the natural folds and creases of Ashton’s body, refusing to gloss over or idealize the realism of the human form.

Life in New York

Neel eventually returned to New York in the next few years, settling in Greenwich Village and finding steady work with the Works Progress Administration (WPA) for the next decade, which funded artists to paint a series of prominent public artworks across the city. Like Neel, various leading radical artists cut their teeth through the program, including Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner. Neel’s portraits of the later 1930s focused on left-wing bohemian characters including artists, writers, trade unionists, and sailors.

One of her most striking portraits of this period was of her new boyfriend, Kenneth Doolittle, 1931, who she paints as a ghostly, ethereal, and deathly pale character with intense eyes. Curator Richard Flood calls Neel’s emphasis on her sitter’s eyes the “entry point into the picture,” carrying with them the individual’s complex psychological emotions. Doolittle and Neel had a tumultuous relationship that ended badly after two years, when Doolittle tried to destroy over three hundred of Neel’s works in a fit of rage, spurred on by his jealousy of her obsession with her art.

Spanish Harlem

Neel left Greenwich Village for Spanish Harlem in 1938 in a bid to escape what she saw as the pretentiousness of New York’s enclosed art scene. “I got sick of the Village. I thought it was degenerating,” she explained in an interview, “I moved up to Spanish Harlem… You know what I thought I’d find there? More truth; there was more truth in Spanish Harlem.”

During these years, Neel had a son named Richard with nightclub singer Jose Santiago Negron, although their relationship later fell apart. Neel found more stability with the photography and documentary filmmaker Sam Brody – together they had another son named Hartley, who they raised alongside Richard together for the next two decades. Her paintings throughout the 1940s and 1950s continued to focus on intimate portraits of the many people in her life, as seen through a modern female gaze.

Neel frequently painted her culturally diverse friends and neighbors from Harlem, capturing their honest grit, spirit, and character. These paintings caught the eye of communist writer Mike Gold, who helped promote her art to various gallery spaces, praising its unflinching portrayal of New Yorkers from all walks of life. Prominent paintings of the period include the solemn portrait of the esteemed social critic and academic, Harold Cruse, made in 1950, which demonstrated Neel’s support for liberal, left-wing politics and the equal rights of African Americans.

In the painting Dominican Boys on 108th Street, Neel paints two children from the streets of New York – children were a common trope considered safe for women artists, but Neel’s young boys are far from sweet and innocent. Instead, they have a street-smart demeanor that seems well beyond their years, posing confidently in adult-style bomber jackets, stiff jeans, and smart shoes. Neel’s portrayal of these boys has the confrontational realism of various female documentary photographers, including Dorothea Lange and Berenice Abbott, revealing her desire to portray the same anthropological observations of ordinary life from a female perspective.

The Upper West Side

From the late 1950s onwards, Neel finally began to achieve widespread recognition for her emotionally arresting portraits that seemed to capture the spirit of the time in which she was living. “I paint my time using the people as evidence,” she observed. Neel moved to the Upper West Side of New York during these years so she could reintegrate with the city’s thriving artistic communities and made a series of frank and surprisingly intimate portraits documenting prominent arts figures including Andy Warhol, Robert Smithson, and Frank O’Hara.

Neel also continued to paint a wide pool of portraits from across society, including friends, family, acquaintances, and neighbors, treating everyone from all walks of life with the same non-judgemental acceptance, acknowledging everyone’s place as an equal in society. She became particularly recognized for her stirring, emotionally complex portrayals of women, who appear intelligent, inquisitive, and unidealized, as seen in the richly complex portrait of her friend Christy White, 1959.

The Female Gaze: Making Neel A Feminist Icon

As the women’s rights movement rose across the United States, Neel’s art was increasingly celebrated, and her fame grew across the country. Between 1964 and 1987, Neel painted a series of frank and directly honest portraits of pregnant nudes. Many of these women had family or friendship connections to Neel and her portraits celebrated the fleshy realism of their bodies and the growth of new life at the heart of humanity, as seen from a female gaze. Denise Bauer, writer and Professor of Women’s Studies at the State University of New York, called these frank depictions of pregnancy “a compelling feminist portrayal of feminine experience.”

Neel was also an active supporter of transgender rights, as demonstrated by her many sympathetic portraits of New York’s queer community, including the stirring Jackie Curtiss and Ritta Red, 1970, two actors and regulars from Andy Warhol’s factory who Neel painted and drew on various occasions.

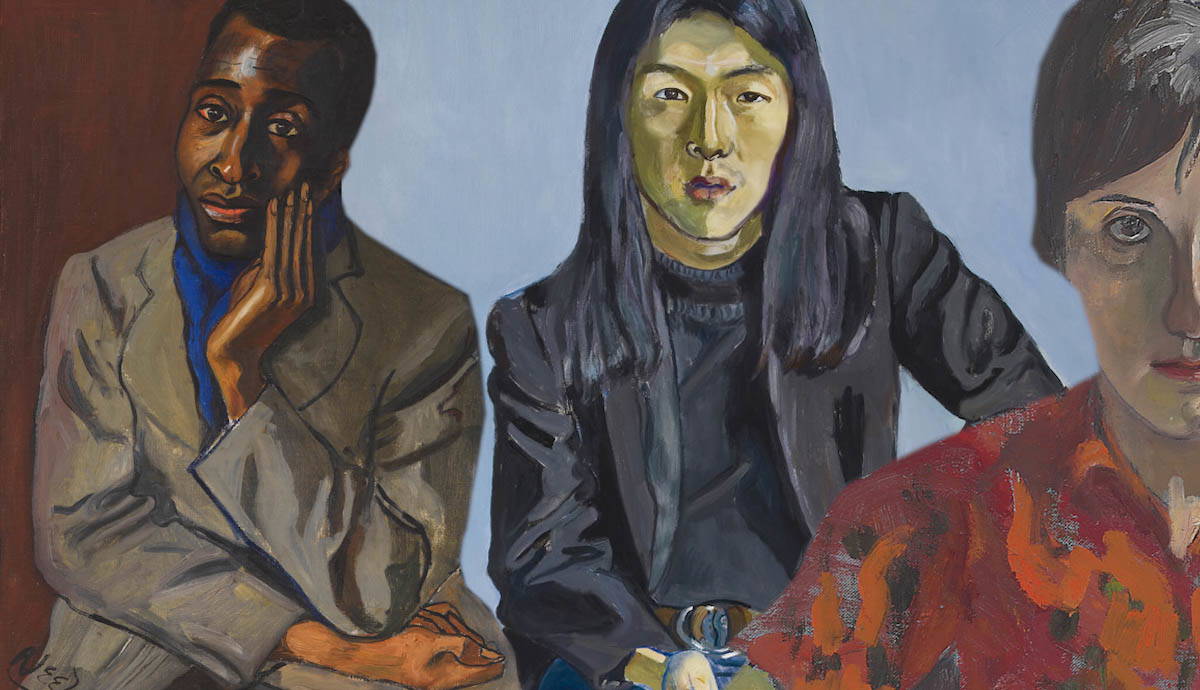

Neel also painted portraits of high-profile public figures who defy gender norms, such as the outspoken Martha Mitchell, 1971, wife of Attorney General John Mitchell under president Richard Nixon and the American-Japanese designer Ron Kajiwara, 1971. When seen together, all these portraits challenged societal norms and demonstrated the growing complexity of femininity, masculinity, and contemporary identity. Neel observed, “(when) portraits are good art they reflect the culture, the time and many other things.”

Alice Neel’s Legacy

It is hard to overstate the impact that Neel’s portraiture and female gaze has had on contemporary art since her death in 1984. A pioneer in equal rights for all, and a humanist who saw the spark of life in everyone she painted, Neel has shaped the practices of so many world-leading artists since, the majority of whom are women. From Diane Arbus’ unflinching documentary photographs to Jenny Saville’s overflowing flesh, Marlene Dumas’ haunting nudes and Cecily Brown’s painterly erotica, Neel showed these artists that feminine ways of looking at the world could be bold, frank, risk-taking, and subversive, encouraging us to see the world in a new way. She also showed how to celebrate the raw and unfiltered beauty of the human form in all its idiosyncrasies, highlighting the incredible diversity that makes up the human race.