Allan Kaprow was born in the year 1927 in New Jersey and died in 2006 in California. He attended New York University and Columbia. At a class taught by John Cage, Kaprow met other experimental artists. One of them was Georg Brecht, who was a member of the Fluxus art movement. It was at this time that Kaprow started to concentrate on art theory. He approached the creation of art philosophically, which ultimately led him to the development of art happenings. Kaprow’s happenings offered an alternative to art that was sold in the form of objects and can therefore be interpreted as critical towards consumerism and capitalism.

Allan Kaprow’s Essay The Legacy of Jackson Pollock

In his essay “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock,” Allan Kaprow described the death of modern painting and how the perishing of this art form aligned with the actual death of Jackson Pollock. Kaprow thought that Jackson Pollock “created some magnificent paintings. But he also destroyed painting.” Pollock’s artworks were more about the “Act of Painting” itself and not about the final product that would eventually end up in a museum or gallery. In his 1958 essay, Kaprow wrote: “Strokes, smears, lines, dots, etc. became less and less attached to representing objects and existed more and more on their own, self-sufficiently.”

He additionally explained that Pollock’s works leave the traditional concept of form behind. When looking at Pollock’s paintings, there seems to be no beginning and no end. The audience can experience the painting from any viewpoint, and they would still be able to comprehend the artwork.

Allan Kaprow offers two future-oriented solutions for this death of painting initiated by Pollock. Artists could either continue to make what he called “near-paintings,” such as Pollock did, or they could “give up the making of paintings entirely.” According to Kaprow, contemporary artists were to use ordinary materials, objects, sounds, movements, and odors, such as “paint, chairs, food, electric and neon lights” to make art. He subsequently described the role of the new artists: “Not only will these bold creators show us, as if for the first time, the world we have always had about us, but ignored, but they will disclose entirely unheard of happenings and events.” (Kaprow, 1958)

Allan Kaprow’s Rules for Art Happenings

But how does a happening work according to Allan Kaprow? In his lecture “How to Make a Happening” Kaprow established 11 rules for art happenings:

- “Forget all the standard art forms.”

- “You can steer clear of art by mixing up your happening by mixing it with life situations.“

- “The situations for a happening should come from what you see in the real world, from real places and people rather than from the head.“

- “Break up your spaces. A single enactment space is what the theatre traditionally uses.”

- “Break up your time and let it be real-time. Real-time is found when things are going on in real places.”

- “Arrange all your events in the happening in the same practical way. Not in an arty way.“

- “Since you’re in the world now and not in art, play the game by real rules. Make up your mind when and where a happening is appropriate.“

- “Work with the power around you, not against it.”

- “When you’ve got the go-ahead, don’t rehearse the happening. This will make it unnatural because it will build in the idea of good performance, that is, art.”

- “Perform the happening once only. Repeating it makes it stale, reminds you of theatre, and does the same thing as rehearsing.“

- “Give up the whole idea of putting on a show for audiences. A happening is not a show. Leave the shows to the theatre people and discotheques.“

18 Happenings in 6 Parts by Allan Kaprow, 1959

18 Happenings in 6 Parts took place in the New Yorker Reuben Gallery and lasted for approximately 90 minutes. As the name of the performance suggests, 18 Happenings in 6 Parts consists of six parts that each include three art happenings. The three happenings always took place simultaneously. The audience was instructed via programs that they should not applaud when the individual parts were completed, but they could applaud after the sixth part. The gallery was split into three rooms by plastic sheets with wooden frames that displayed references to some of Allan Kaprow’s previous works. Since the gallery was divided into rooms and the art happenings took place simultaneously, the audience was not able to see every single performance.

The performance was heavily scripted, which was typical for the artist’s happenings. It showed a number of simple acts, for example, a woman squeezing oranges and drinking the juice, people playing instruments, and artists painting on a canvas. The breaks between performances were indicated through the sound of a bell. Allan Kaprow made the audience members a part of the happening by handing out cards that informed the individual viewers in which room they had to be at what time.

Kaprow’s Art Happening Yard, 1961

The happening Yard took place in the courtyard of the Martha Jackson Gallery. Allan Kaprow filled the space with old tires and wrapped the sculptures that were exhibited in the courtyard with black paper. The audience climbed over the tiles while Kaprow piled them. The use of old tires reminds us of Kaprow’s statement from his essay “The Legacy of Jackson Pollock”: “Objects of every sort are materials for the new art: paint, chairs, food, electric and neon lights, smoke, water, old socks, a dog, movies, a thousand other things which will be discovered by the present generation of artists.”

The Yard can not only be seen as a happening where people interact with each other and with the tiles, but also as an artistic environment. For Allan Kaprow, environments should constantly change and offer a space that the audience can physically enter. Yard created a place in which people were as much part of the artwork as the randomly arranged tires. It exemplifies a shift regarding what art is. Art happenings like Yard challenged the use of traditional materials.

In his book “Assemblage, Environments & Happenings,” Kaprow depicted a photo of his artwork Yard and him standing on top of the piled tires next to a photo of Pollock standing on a canvas and painting. Pollock’s paintings and Kaprow’s Yard resemble each other visually through the seemingly random spilled color and tires that have been thrown together. Both artworks share a process where the artist used his whole body for the creation. Jackson Pollock and Allan Kaprow spread the material of their artwork on either a canvas or in a courtyard.

Unlike Pollock though, Allan Kaprow used everyday materials and left the concept of painting behind. According to Kaprow, Pollock almost gave up painting through his innovative method of action painting since he did not adhere to the traditional rules of art. Inspired by Pollock’s work, Kaprow wrote: “Pollock, as I see him, left us at the point where we must become preoccupied with and even dazzled by the space and objects of our everyday life, either our bodies, clothes, rooms, or, if need be, the vastness of Forty-Second Street.” (Kaprow, 1958)

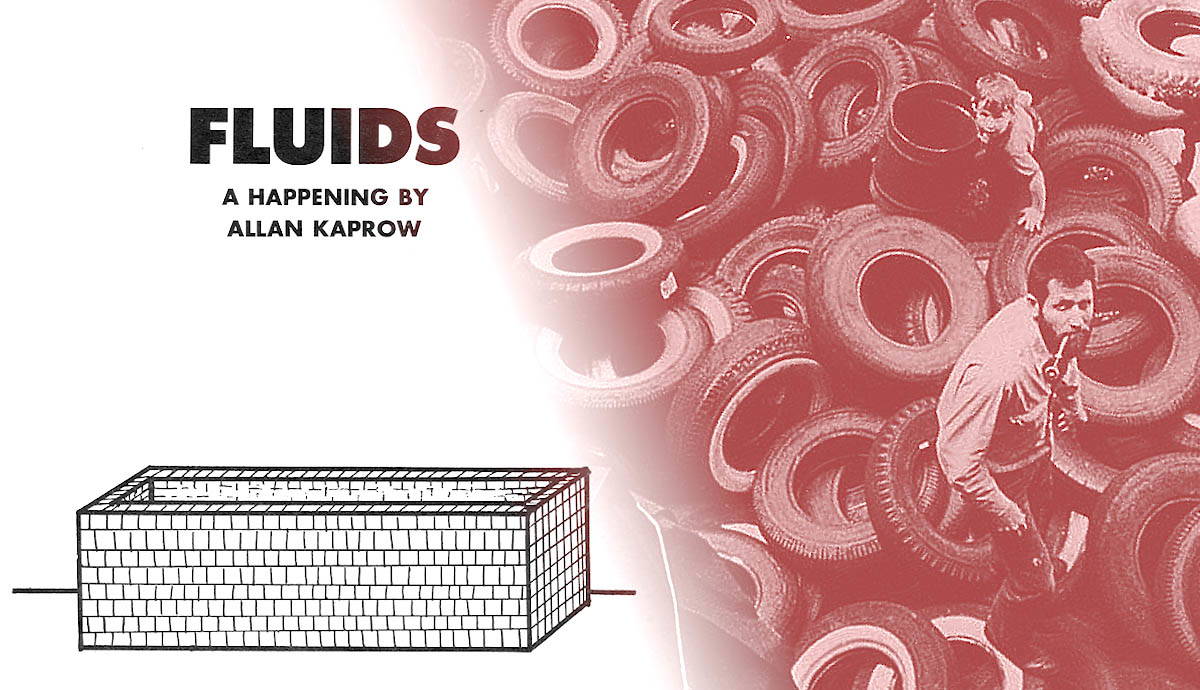

Allan Kaprow’s Happening Fluids, 1967

The happening Fluids took place in different public places in Pasadena, California. With the help of people who lived in the area, Kaprow built rectangular structures with walls out of ice blocks and let the constructions melt away on their own until nothing was left of them. The exhibition poster for Fluids was visible on various billboards in Pasadena and invited people to join the happening with the following statement: “Those interested in participating should attend a preliminary meeting at the Pasadena Art Museum, 46 North Los Robles Avenue, Pasadena, at 8:30 P.M., October 10, 1967. The happening will be thoroughly discussed by Allan Kaprow and all details worked out.”

Kaprow made the procedure of the happening accessible to the public and consequently challenged the exclusive status of making art. The creation of art was therefore no longer confined to the artist but was open to everyone. This democratic way of making art was typical for Kaprow’s work. The audience was included in his art happenings and their presence and acts played an important role in the performance of the artwork.

The poster also depicted the original idea for the happening: “During three days, about twenty rectangular enclosures of ice blocks (measuring about 30 feet long, 10 wide and 8 high) are built throughout the city. Their walls are unbroken. They are left to melt.” Fluids can be interpreted as a critical display of human labor in a capitalist society that is based on work and consumerism. The result of the hard work is only fleeting until it melts away completely and ceases to exist.

Fluids is also an artwork that cannot be physically sold on the art market. The temporary material showcases the impossibility of selling the work, even though people spent hours of their time and manual labor to build the construction.

However, Kaprow’s Fluids has been reinvented in several cities and on several occasions. It was for example shown by the Tate in 2008 and has also been reconstructed by the Nationalgalerie in Berlin in 2015. Today, Fluids can be interpreted as an indication of the dangers of climate change through its display of melting ice blocks.