Alma Mahler had an appalling yet unique and remarkable persona. It was not her creative output, but rather her tumultuous personal life, that earned her a place in history. An amateur composer, she was worshiped by some for her beauty and hated by others because of her cruelty. She surrounded herself with the most remarkable men of her time—Gustav Mahler, Oskar Kokoschka, and Walter Gropius—and treated them mercilessly, attempting to shape them into geniuses of her liking. Even posthumously, she took control over their lives, editing diaries and looting archives.

Alma Mahler: The Prettiest Girl in Vienna

Alma Schindler was a gifted girl with a keen interest in music. Her father was the famous Austrian landscape painter Emil Jacob Schindler. Alma’s parents had a strained relationship, and this dynamic could not leave the children unaffected. While the father entertained his daughters with art, music, and games, the mother desperately tried to maintain a sense of order in the house, forcing Alma and her sister to study mathematics and social etiquette. In her diaries, Alma described her father as her childhood hero and her mother as a repulsive, dishonest figure and a domestic oppressor with a face always distorted in a screaming rant.

Alma studied piano and composing with the best teachers in Vienna and showed considerable progress and talent. She practiced for hours every day yet avoided playing in public, regarding music as a private and intimate affair. After her father passed away, Richard Wagner became Alma’s main hero and aspirant. Soon, she started to compose her own songs and even had ambitions to write an opera but she never succeeded in that. Due to the internalized misogyny that was typical for her time, Alma Mahler did not believe in women’s capabilities to create meaningful works of art. She even complained about her feminine lack of seriousness.

Apart from music, Alma was occupied by her lively social life. Her family’s home was the center of gatherings for artists, composers, and intellectuals. From her mid-teens, she started to attract increased attention from men and she enjoyed it, figuring out how to use it to her advantage. Aged seventeen, she met the famous painter, Gustav Klimt, who was twice her age. The attraction was immediate and mutual, yet it did not last long. Klimt was notorious for his amorous adventures and certainly did not see his potential affair with the teenager as serious.

The beauty and charm of the young Alma Schindler mesmerized Viennese intellectuals of all ages. Dubbed the most beautiful girl in Vienna, Alma soon learned to use her looks to compensate for her dysfunctional family. She craved attention, care, and love but only understood it through worship and submission. She started to self-identify through dominance over her admirers, searching for intense emotions and unconditional love. She tested love’s limits by alternating fits of exaggerated passion followed by humiliating rants, earning the reputation of a dramatic femme fatale.

Raising a Genius: Alma’s Three Marriages

In 1902, she married the composer Gustav Mahler. She was nineteen, while he was almost forty. Their ten years of marriage were an ongoing battle for household dominance: Alma craved constant attention and praise, while Gustav needed a companion for his work-centered life. The most offensive thing for Alma was Mahler’s dismissal of her interest in music. He always seemed to let her know that the Mahler family had room for only one professional composer. In her notes, Alma interpreted this as Mahler forbidding her from playing altogether. She retorted by publicly criticizing her husband’s music, while he tried to cover embarrassment with laughter.

The relationship was far from happy, as Gustav Mahler felt more comfortable with his music than with his wife. Alma felt bored and abandoned, blaming Mahler for ruining her potential career. She felt no love towards her two daughters, jealous of the attention they received from her husband. With her resentment growing, she resorted to a string of extramarital affairs.

In 1910, Alma met a young German architect Walter Gropius, and almost immediately began a poorly concealed affair. Mahler’s reaction expressed guilt rather than anger. He wrote several musical pieces for Alma and even assisted in publishing some of her composed works. Still, their relationship with Mahler was virtually over, although legally, it would end only with Mahler’s death in 1911. Alma saw a remarkable sense of potential in others, carefully choosing promising partners and getting rid of those who bored her. In a letter to Gropius, then an unknown architect, she noted: “The more you are and accomplish, the more you will mean to me.” She saw herself as the mentor to talented and ambitious men who would nurture them into success.

Yet, the five-year marriage to Gropius did not bring them much joy. As it turned out, without the thrill of forbidden extramarital romance, the lovers were not as interested in each other as they thought they would be. Despite the mutual agreement to get a divorce, Alma hired a prostitute and a private detective to accuse Gropius of infidelity and settle the case in her favor. After the divorce, Gropius occupied himself with running the Bauhaus. Alma moved on, marrying the poet Franz Werfel, her longtime lover who entertained her while Gropius fought in World War I.

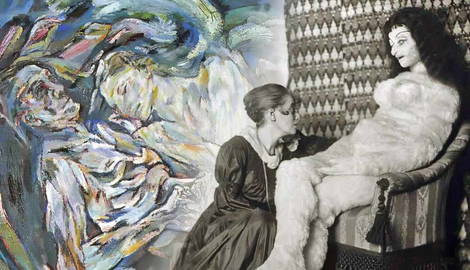

The Kokoschka Affair

Perhaps the most scandalous love affair in the life of Alma Mahler became one of the most notorious cases of obsession in the history of art. In 1912, Alma met a young and eccentric Expressionist painter Oskar Kokoschka. Unlike most of her previous lovers, Kokoschka was impulsive, unpredictable, and a bit brutish. He claimed that only Alma’s love could tame his inner beast and keep him human, and she gladly played into that. His aggressive and violent jealousy flattered Alma, who fed off the intense emotional turmoil and praise. The affair was sadomasochistic, with both sides endlessly tormenting each other.

Kokoschka planned to marry her, but Alma was not so enthusiastic. In her notes, she mentioned she normally avoided affairs with artists because most of them lacked personality. The Austrian Expressionist had plenty of personality—even too much to be reshaped into Alma’s pet genius. The final blow to the relationship was Alma’s abortion. The artist respected her choice but never fully recovered from it.

Soon after the breakup Alma married Walter Gropius, and Kokoschka left to the frontlines of World War I. Hearing the news of the artist’s severe injury on the battlefield, Alma went to his studio and stole all her letters and dozens of remaining sketches and drawings. This hideous gesture, however, was not the final point of their relationship.

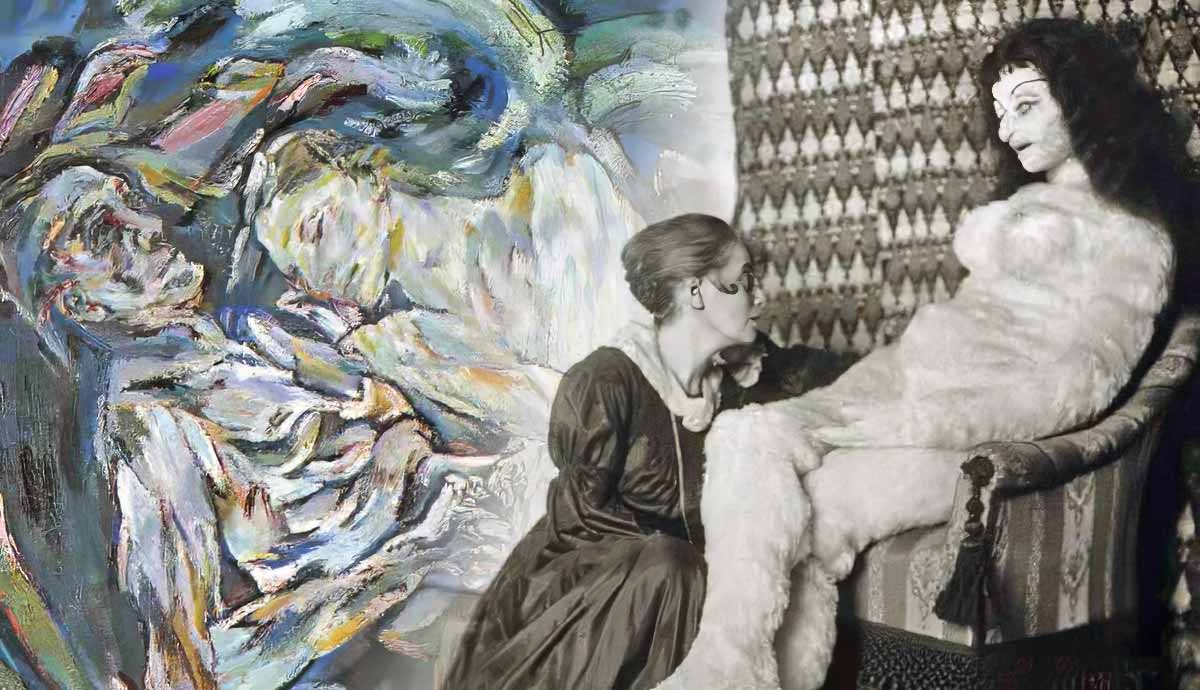

In 1918, a distressed Kokoschka ordered a life-sized doll from a Viennese doll maker. The order came with elaborate instructions and demands since the doll had to be the exact copy of Alma. Upon receiving a plush monstrosity made from polar bear skin, Kokoschka flew into a rage. Still, he kept this caricature of his idol as a monument to his failed romance and even dressed it in expensive Parisian lingerie and silk dresses. On several occasions, he took it with him to dinners and theaters, appalling the public. Yet he realized he needed to break free from Alma once and for all. During a party in his garden, he decapitated the doll and then spilled a bottle of red wine over it to finish the ritual.

Alma Mahler’s Notorious Personality

According to Alma Mahler’s contemporaries, the dominating traits of her characters were the overwhelming sense of entitlement and pathological cruelty directed at everyone she knew, particularly men who were unlucky enough to interest her. Without a second thought, she ruined a longstanding friendship between Wassily Kandinsky and Arnold Schonberg by falsely accusing the former of radical anti-Semitism. The reason for this was personal. A year before, Alma desperately tried to seduce Kandinsky who happened to love his wife Nina too much to react, which Alma took as an insult.

The accusations of anti-Semitism coming from Alma were especially ironic, since, over her lifetime, she did not attempt to hide her bigotry and prejudice. Even though she painstakingly edited her diaries to make them look better, she kept spewing xenophobic remarks toward everyone Jewish, including two out of her three husbands. Some historians, like Alma Mahler’s biographer Oliver Hilmes, believe she deliberately sought attention from Jewish men to dominate, humiliate, and feed her sense of inherent superiority.

Alma had no interest in the racial theories of her time, using her xenophobia as a way of expressing dominance rather than framing her worldview. She was notoriously superficial, impulsive, and unable to focus, yet boasted her supposed “Aryan cleverness” with which she balanced the “Jewish degeneracy” of her men. Once, she met Adolf Hitler and was charmed by him. Yet, she had to re-evaluate her judgment when she realized, rather belatedly, that she, as the wife of the Austrian-Jewish poet Franz Werfel, was in danger.

The Alma Problem: Alma Mahler vs Historians

As World War II began, Mahler and Werfel escaped to the US. There, Alma continued to live the life of a wealthy socialite, but she also had another mission. Widowed for the second time in 1945, she made her goal to secure her own legacy by taking control of the memory of her two late husbands.

Today, music historians refer to this case as The Alma Problem. Alma Mahler’s contemporaries saw her as the main data source on the composer—his habits, characters, and beliefs. As dominant and manipulative as ever, Alma took control of the narrative. She destroyed most of her letters to Mahler and forged an unidentifiable number of notes and documents in his archives. She mercilessly edited every text containing even the slightest undertone of criticism towards her or her actions or contradicting the image of Mahler she wanted everyone to see. Since Alma was the only witness to many events of Mahler’s professional and private life, historians could not possibly recover the truth.

One of the reasons Alma became so involved with Gustav Mahler’s archives was the desire to “clean” his name of his Jewish heritage. In conversations with friends, Alma boasted how she made her late husband “brighter” by influencing him with her Aryan mind. She saw her life mission in making her men allegedly better by subduing them. Once the subduing tactics malfunctioned, like with Kokoschka and Gropius, she quickly got rid of her failed experiment.