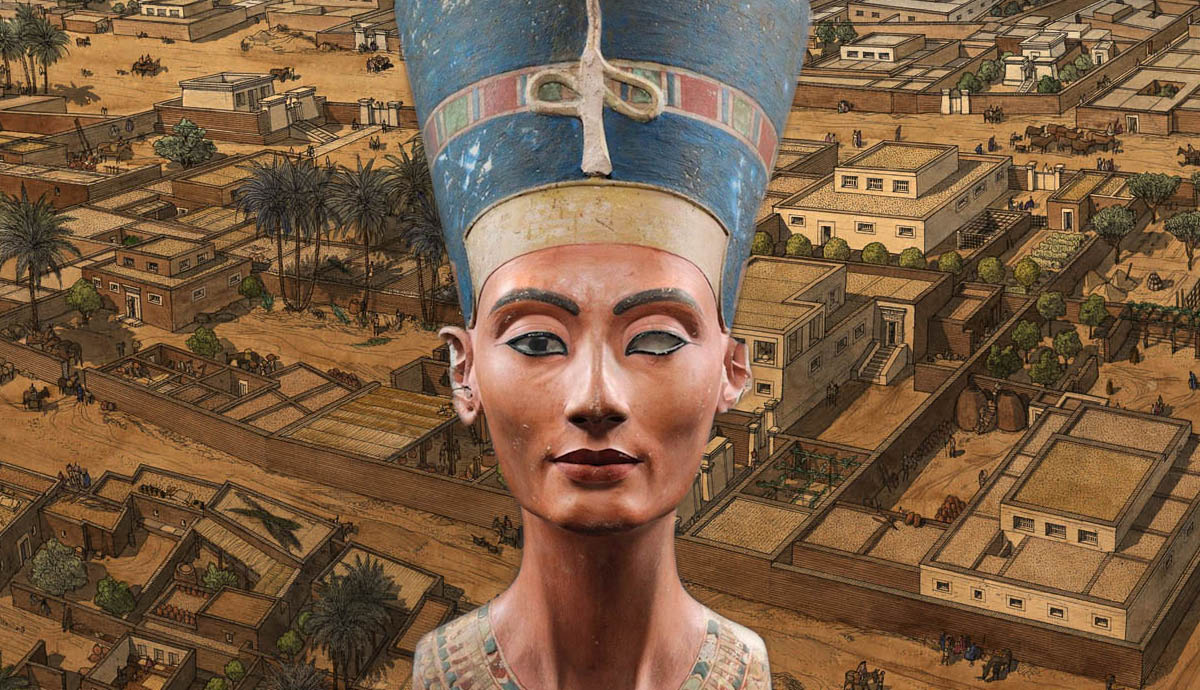

Akhenaten is well-known for his controversial rule and revolutionary ideas. However, Amarna, the city inspired by his divine vision, also happens to be a treasure trove for Egyptologists and anyone interested in archaeology. The longest-standing archaeological site in Egypt, Amarna is still revealing the secrets of a once-thriving ancient capital.

Amarna: The City of Akhenaten

The 18th Dynasty of Ancient Egypt was full of intrigue. Some of the most famous pharaohs come from this period. Akhenaten is perhaps one of the most infamous.

In the 4th year of his reign (c. 1350 BCE), Akhenaten claimed that a vision sent by his god, Aten, the only god he acknowledged, led him to a large tract of land on the Nile’s east bank. In a political power move, Akhenaten decided to move Egypt’s capital to this tract of land and began the construction of a new city dedicated to Aten.

Akhenaten named the city Akhetaten. In the modern-day, we refer to it as Amarna. This city was a unique cultural landscape that was used only for a short time during Akhenaten’s 17-year reign. Today, Amarna is the perfect snapshot of life during Akhenaten’s time; an Egypt torn by the new ideas of an enforced monotheism. It is also one of the most complete examples of an Ancient Egyptian city discovered by Egyptologists.

Finding Amarna

Amarna was first uncovered during an expedition by Napoleon in the 18th century. Although people still occupied the site, they were unaware of what it was. Throughout the 1800s, the tombs of Amarna were explored, while the Amarna Letters were discovered in 1887. The letters shed new light on the city, Akhenaten’s life, and the Egyptian state.

Amarna was excavated several times in the 1900s. First in 1911 by the Deutsche Orient-Gesellschaft expeditions, then by an Egypt Exploration Society between 1921-1936, and in the 1960s by the Egyptian Antiquities Organization. Amarna came to the forefront again in 1977, when Barry Kemp began work at the site, leading to the production of Amarna Project documents, the fruit of Kemp and his team’s work at the site, which is still ongoing.

The Amarna Project

Amarna is one of the longest-running archaeological sites of Ancient Egypt. This means that archaeologists have had the chance to learn a lot about this unique site. The Amarna Project website offers a comprehensive look at its excavation history, with reports from each year and major discoveries, guidebooks, downloadable magazine issues, and much more.

An Abandoned City

Amarna was completely occupied only during Akhenaten’s reign. Soon after his death, Amarna was abandoned. Still, the site is a blessing in disguise for archaeologists. Less of a blessing was the city’s deconstruction, which took place several years later, likely at the hand of Horemheb, who had many of the city’s building blocks repurposed elsewhere.

Amarna: Workmen’s Village

The Workmen’s Village was a small settlement separate from Amarna. Workers who toiled at building tombs lived here and remained even after the capital was moved back to Memphis. The workers of the village were nearly completely self-sufficient. Here, they kept animals, worshipped at their chapels, and buried their dead.

Because of the continued habitation and the sheltered nature of the location, the Workmen’s Village is a snapshot of what life was like in a smaller Ancient Egyptian settlement. Interestingly, more structures were found intact and more organic matter collected here than in any other location in Amarna.

The North and South Suburbs at Amarna

The North Suburb and the South Suburb were Amarna’s residential areas. The suburbs were filled with large houses with personal farms built among smaller, worker homes. There was no clear delineation between classes outside of the grandeur of the homes themselves.

Personal wealth or status did not seem to play a part in the urban planning of these areas. In fact, there did not seem to be much urban planning at all and compared to other cities of the New Kingdom, Amarna had a surprising lack of direction.

In these areas, anyone could choose how and where to build their homes. This seemed to have been based on personal preference rather than a strict set of rules asserting that Amarna was different. Here, every person was a worker and every home produced something of value. Even larger estates for the king’s advisors had their own small farm areas.

Amarna was very much a new city, unbound by tradition, which is also reflected in its lack of in-depth city planning.

When the city was abandoned, many households left objects behind. These included daily items that were replaceable, too big to transport, and more. Unfortunately, many of these items were lost due to robbery, careless excavation, or more.

The Central City Area

Amarna’s Central City was home to two of Akhenaten’s temples to Aten, as well as the state palace. Administration buildings and other necessary royal buildings were packed together here. Because of this, the Central City might be the most important area of Amarna.

The Central City is the only state center archaeologists can properly examine, as the area remains almost exactly as it was back when it was active (if we do not account for the environmental damage caused during the span of 3,000 years).

It was in this area that Amarna Letters were discovered. These tablets record the correspondence between Akhenaten, Amenhotep III and foreign powers across the ancient world, offering valuable perspectives on diplomacy during the Amarna age.

The Main City Area

One of the most famous findings from the excavations at Amarna was the bust of Nefertiti. This singular artwork, found in the workshop of Thutmose, the royal sculptor, in 1912, is one of the most beautiful and intact pieces from the period. Indeed, it’s one of the best representations of Egyptian art ever found.

The house of Ranefer, a royal chariot officer, was also found in the Main City area, where most of Akhenaten’s advisors, priests, and high-ranking officials lived in this area.

Years after the death of Akhenaten and Amarna’s abandonment, Horemheb returned to take the city apart and erase the Amarna period from the record. Horemheb consistently used building material from Amarna’s main city area in other construction projects. This means that we might never know how this part of the city actually looked like.

Akhenaten’s Palaces and Temples

Akhenaten’s temples and palaces are some of the buildings we know the least about. The unique architecture and art of these places of luxury and worship are lost to time, looting, and the drive to strike Akhenaten from history.

However, there are a few things we do know. The buildings would have certainly been a sight to behold. Many of the Aten temples (including the Great Aten Temple) are thought to have manipulated light from the sun to create dazzling, reverent displays. Akhenaten and his family lived in the North Palace, a large complex with areas for the members of the royal family. The complex also included homes for servants and certain officials, as well as outbuildings for baking, production, and other pursuits. While the palace was not as grand as others (e.g. the great palace of Amenhotep III), it is amazing how quickly it was built following the city’s founding.

Amarna: Akhenaten’s City

Amarna was abandoned shortly after Akhenaten’s death. His successor, Tutankhaten, changed his name to Tutankhamun , revived polytheism, and re-established the capital at Memphis.

Amarna is a great example of what people bound together by belief can do. The city sprang up quickly, and each resident produced goods to help the community thrive.

As the site is preserved in good condition, it is a great place to study life under Akhenaten’s reign and an invaluable gem in the crown of Egyptologists. That’s one of the reasons that the excavation efforts have continued, even today.

Because of Akhenaten’s heretical reform – or perhaps despite it – Amarna lives on. Restoration efforts are ongoing to rebuild the Great Temple of Aten, while work continues elsewhere on the site. Though Akhenaton’s successors tried to remove his name and identity from history, the pharaoh’s memory is still very much alive – especially at Amarna.