History and archaeology have often portrayed megalithic architecture as a cultural phenomenon specific to ancient European peoples, focusing on the study of mortuary and ritualistic constructions dating back to the beginnings of the Neolithic Era. In reality, megalithic structures have been found all over the globe, including the American continent, where different pre-Columbian cultures erected large stones to commemorate gods, represent religious symbols, or build sacred or mortuary spaces.

Terminology: Megaliths and Megalithism

In archaeology and history, megalithism is the study of large pieces of rock with cultural significance erected by ancient civilizations and communities. It has been mainly focused on “primitivism,” studying the intellectual capacities of ancient communities, investigating, among other questions, the transition of human thought and beliefs toward the material representation of symbols and religion.

Megalithic constructions started during the Neolithic period and continued until the Age of Bronze. They take a number of forms, including, for example, vertically erected single pieces of rock or an assemblage of several rocks following geometric or architectonic formations, with different degrees of human intervention. They may incorporate carved or painted representations of entities or delineate sacred or ritualistic spaces when rocks are placed in lines or circles. Funerary chambers made of rock, which could be placed over the ground or buried as a coffin, as well as altars, temples, monuments, and, in some cases, astronomical observatories have also been discovered.

The word megalith was first used by the antiquarian Algernon Herbert in 1848 to refer to the standing rocks found in the prehistoric site of Stonehenge in England. “Megalith” comes from the ancient Greek mega (great) and lithos (stone).

Taking Shape: Megalithic Formations

The most common type of megalithic formation is called a menhir, a word from the Brittonic maen or men (stone) and hir or hîr (long). Menhirs can be found in isolation or grouped together, forming lines or circles—in such cases, they are called cromlechs, Stonehenge being the most well-known example.

Another kind of megalithic formation is called a dolmen, which consists of two vertical monoliths arranged in parallel, supporting a third laid horizontally, forming a table-like square. Dolmens primarily served mortuary purposes, and in some cases, the insides were used as tombs, as a form of protection.

Megalithic architecture can also include horizontal monoliths without inferior support, known to lay in a “capstone style” arrangement, or more complex constructions such as walls, passages, or temples with multiple chambers.

Historically, megalithism has primarily focused on European sites, which include places such as the stone circles in Stonehenge (3100–1600 BC) and Avebury (3000 BC) in England, the monument of Brú na Bóinne (3200 BC) and the site of Carrowmore (3700–2900 BC) in Ireland, the Gavrinis tomb (4250-4000 BC) and the Carnac Stones (4500-3300 BC) in France, and the Cromlech of the Almendres (5000-4000 BC) in Portugal, the oldest megalithic construction found in the European continent. This intensive attention on European sites has resulted in scientists ignoring many other megalithic formations in other parts of the world, making non-European megalithism a relatively recent field of archaeological interest.

Rethinking Eurocentric Megalithism

In his book Megaliths of the World, megaliths expert Luc Laporte explains how, apart from the lost culture of San Agustín, which has featured in some megalithic studies, the American continent is rarely cited as part of the subject in archaeology. He discusses how the interest there has been in megalithic architecture on the continent has been based on “efforts to compare large mounds of the Mississippi Valley with the megaliths of Neolithic Europe or the large Mayan stelae in Central America with the deer stones of the Mongol plains.”

His point is a response to an extensive historical tradition of Eurocentric monumentalism, which determines which sites are worth studying and admiring, including those featuring the large constructions of Old World civilizations. While monumentalism studies large-scale constructions made with any material, megalithism specializes in stone-made constructions because this material has specific characteristics of texture, color, durability, and, most importantly, extraction, collection, and processing technologies.

In general, it is believed that megaliths were important for pre-Columbian indigenous communities and civilizations, particularly because they believed that large stones and petroglyphs could embody sentient beings, often attributing vital force and great power to them. The oldest Western historical records of megalithic structures on the American continent date back to the 16th century, during Spanish colonization, when an Augustinian priest registered menhirs in Huanchaco in Peru.

Notable Megalithic Sites on the American Continent

Monoliths have been found throughout the Andean Cordillera, both free-standing and in architectural complexes. One is Cerro Sechín in the Casma Valley of Peru, a wall comprising 90 monoliths with carved war motifs. Other megalithic sites in the region include Qulosara and Cerro Collona on the Ecuador-Peru border and Cerro Parihuaca and Cancha Siruni in the Peruvian Andes. Notably, many of these megaliths are still used for indigenous rituals and ceremonies today.

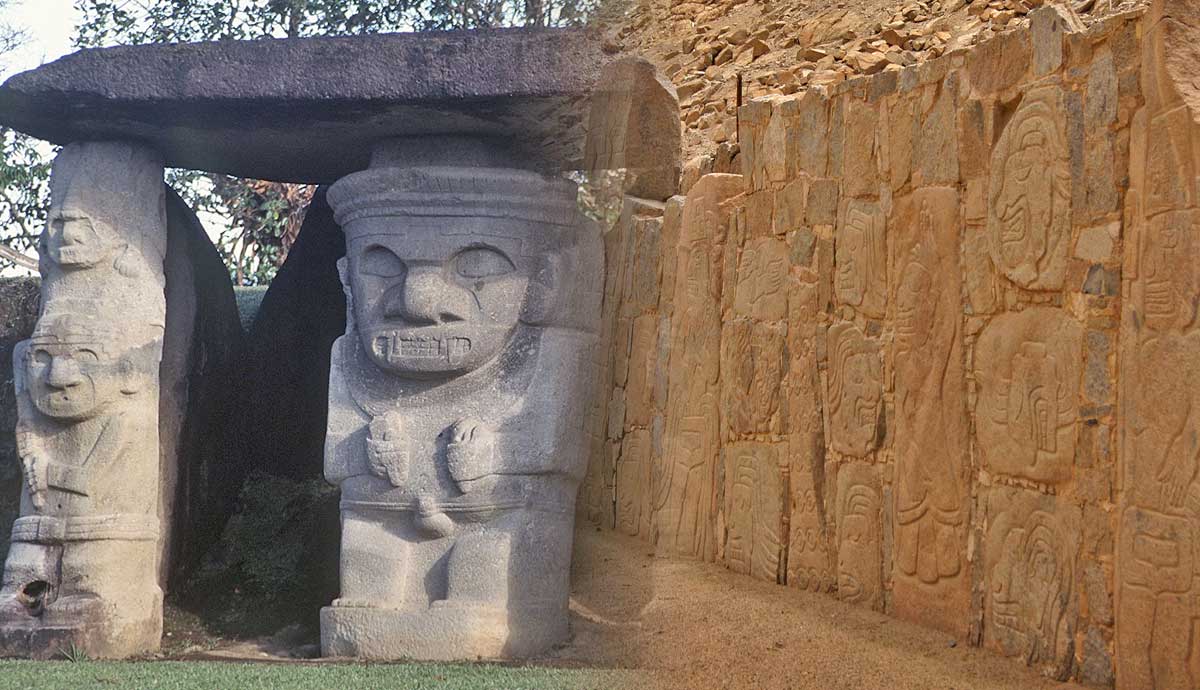

Other important megalithic sites are found in the northern part of South America, in what is now Colombia. The country’s most famous megalithic complex is San Agustín, an archaeological park home to carved vertical monoliths representing anthropomorphic figures and mortuary dolmens. These constructions are attributed to an ancient culture that has remained mysterious for local and international archaeologists; no one knows how or why they disappeared.

The first historical account of archaeological structures in San Agustín was recorded in 1758 by Franciscan monk Juan de Santa Gertrudis, who condemned the statues as the devil’s work. Later, in the early 19th century, the Italian geographer Agustín Codazzi made them famous after completing the so-called Expedición Corográfica, an expedition to create the first record of the region’s biodiversity. Codazzi suggested that the Andoque people had constructed the statues and temples during the Spanish colonization. However, the timeline remains unclear to local archaeologists. Thanks to the fame that the statues acquired after Codazzi’s intervention, the site of San Agustín was heavily looted. Some statues ended up in the Ethnological Museum in Berlin, and the Colombian government is demanding their repatriation today.

Many other megalithic sites have been found in other regions of Colombia. In Boyacá, far north of the country’s capital, Bogotá, one of the most prominent sites is called El Infiernito (The Little Hell), a great archaeological area located in the village of Moniquirá, where a collection of monoliths belonging to the Muisca culture is currently being exhibited. The site features different monoliths placed in lines, serving as an astronomical observatory. Vertically isolated single stones featuring phallic motifs are also present, standing up to 4.5 meters (14.75 feet) tall and weighing up to 30 tons.

Another place known for its phallic menhirs is the Los Menhires Archaeological Park in the Tafí Valley province in Tucumán, Argentina. Other similar dolmen-like funerary chambers have been found in the Quindío region, part of the Quimbaya culture, and in the old village of Guatavita, which was intentionally flooded to create a reservoir. Another important site can be found in the Sierra Nevada del Cocuy, where different menhirs have been found and which are still meaningful sites for the U’wa people of Colombia.

Other smaller megalithic sites have been found around the Virgirina Valley in northern Venezuela, the Guiana Shield, the Amazon rainforest, and in Central America and the Caribbean, including in the Dominican Republic, the British Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico. In the Caribbean Islands, megaliths have been found to serve to establish plazas, ballcourts, and ceremonial spaces, which include the sites of Las Flores (700-1200 BCE), Tibes (900-1200 BCE) and Caguana (1210-1450/1500) and Bateyes de Viví (1225-1445 BCE).

Rejecting Ancient Alien Theory

Today, it is common to find television programs investigating the origins of “mysterious” ancient megalithic constructions, often attributing them to ancient alien intervention. Some, for example, sow doubt based on similarities in pyramid-shaped megalithic temples that are common among different cultures, pointedly ignoring the fact that a pyramidal shape allows for a better distribution of the material’s weight so the structure does not fall. They also speculate about the supposed alien intervention “necessary” for the construction and erection of large-sized rocks.

The great historical tradition that has conceived of primitive communities (especially non-European ones) as savages and the contemporary (mostly Western European) modern human as the epitome of civilization has influenced such speculation on non-Western cultures’ intellectual and technical capacities. As Sarah E. Bond writes in an article for Hyperallergic, theories from pseudoarchaeology offer contact with aliens as the only possible solution to the “mystery” of ancient megalithic constructions. This viewpoint holds a deep-rooted racism that is expressed, as Bond explains, in the disproportionate speculation surrounding non-Europeans versus Europeans, with the former always more vulnerable to such questions made by “Western denialists.”

Historians and archaeologists still have much work to do to fully develop studies of megalithism on the American continent. The local terrain is still subject to further inquiry that will serve to build knowledge of ancient communities living in the American territories before the European invasion. Megalithic constructions demonstrate how the materialization of cultural symbols reflects high intellectual and technical development that needs to be studied to advance knowledge about peoples’ origins in this part of the world.

Bibliography

Laporte, L., Large, J. M., Nespoulous, L., Scarre, C., & Steimer-Herbet, T. (Eds.). (2022). Megaliths of the World. Archaeopress Publishing Ltd.

Reichel-Dolmatoff, G. (1972). San Agustín: a culture of Colombia (Art and civilization of Indian America). Thames and Hudson.