In 525 BCE, the Achaemenid Persians and the Egyptians were two cultures going in very different directions. The Persians had embarked on a policy of imperialism, building the Achaemenid Empire on the ruins of several older cultures, including ancient Egypt. Although the Egyptians were a much older culture, they were in the middle of their Late Period, in which various foreigners took turns ruling the Nile Valley. The Persian conquest of Egypt was bloody and difficult, but winning peace in the land of the pharaohs was even more difficult.

The Achaemenid Persians

In order to understand the complexities of Persian rule in Egypt, it is important to begin hundreds of years prior in Persia. The Achaemenid Persians originated as a tribal society in the region of Fars in southern Persia (modern Iran). The Elamites were the first notable people to rule this region, followed by the Medes. The Medes and Persians were ethnically related, as both were Indo-European-speaking peoples, although the Medes were more urbanized and organized.

The Achaemenid Persians claimed their lineage began with a ruler named Achaemenes, which is how the dynasty was named. The Persians also recognized the Elamites as their predecessors in many ways, with Achaemenid kings using the title “King of Susa.” The city of Susa was the Elamite capital, and when the Persians later created their vast empire they made it one of their capitals as well.

The Persians developed their culture under the rule of the Medes, but by the mid-sixth century BCE the Persians were ready to assert their independence. When Cyrus II (Cyrus “The Great” (ruled 559-530 BCE) came to the Achaemenid throne, he took the dynasty in a new direction. Cyrus engaged the Medes in an open war from 553-550 that resulted in an Achaemenid victory, making them the undisputed lords of Persia. Cyrus followed up his victory over the Medes by conquering older, more refined Near Eastern kingdoms. First, he conquered the wealthy Lydian empire in about 546 BCE, before taking Babylon in 539 BCE. Cyrus’ successor, Cambyses (ruled 530-522 BCE), then accepted the mantle of conqueror by taking Egypt in 525 BCE.

The Installation of the Twenty-seventh Dynasty

Cambyses’ conquest of Egypt is not well documented, with only two texts relating the event. The most contemporary text is a naophorous statue of a man named Udjahorresnet, who served as an admiral under Psamtek III (ruled 526-525 BCE). Udjahorresnet was also a physician and a high-priest of the goddess Neith, patroness of the city of Sais. He would have had access to temple archives and was quite educated, which is probably why Cambyses chose to make him his personal doctor. Udjahorresnet’s statue relates some of the destruction the invasion brought to the country.

“Udjahorresnet, who acts as the administrator of the palace, (who is the administrator of the palace), Heriep priest, Renep priest, Wadjet priest, prophet of Neith foremost of the Saite nome Paftuaneith. He said, ‘Cambyses, the great chief of all foreign lands, came to Egypt with a large international military force and conquered the entire country. After they occupied the country he was made the king of Egypt and ruler of the world. His majesty made me the chief doctor.’”

The other source that relates this is by the second century CE Greek author, Polyaenus, in his Strategms of War. Because Polyaneus wrote his account about 600 years after the event, many people approached it with skepticism. With that said, Polyaneus does provide a rather entertaining account of how the Persians used the Egyptians’ piety against them. He wrote that the Persians hurled sacred animals from catapults at the Egyptians, who then “instantly checked their operations.”

Persian Kings on the Egyptian Throne

Cambyses and his successor, Darius I, “The Great” (ruled 522-486 BCE), both physically sat on the throne of Egypt. Because of this, modern scholars have learned much about the nature of Persian rule in Egypt, which presents a complex picture. One of the more negative accounts of Cambyses was written by the fifth-century BCE Greek historian, Herodotus. Herodotus wrote that Cambyses assassinated his Egyptian predecessor, Psamtek III, by forcing him to drink bull’s blood. The Greek historian also stated that Cambyses slew the sacred Apis bull in a fit of anger.

Both of these accounts have been questioned by modern historians, yet it is likely he did have his predecessor murdered. How Cambyses had Psamtek III killed will likely never be known, although it is unlikely bull’s blood, which is normally nonfatal, was the weapon.

Although Cambyses’ rule over Egypt may have begun with a violent invasion and the assassination of the last Egyptian pharaoh, things quickly changed. The Udjahorresnet statue adds that after the invasion, Cambyses refurbished the Neith Temple in Sais.

“I asked Cambyses to banish the foreigners from the Temple of Neith and restore it to its former greatness. His majesty ordered the expulsion of all foreigners who were residing in the confines of the Temple of Neith by throwing out their beds and any other offensive items they left behind. . . His majesty ordered the purification of the Temple of Neith, giving all of her people to it.”

The validity of Herodotus’ account of Cambyses’ murder of the sacred Apis bull has also been questioned in light of Egyptian hieroglyphic texts. The Apis bulls were interred in a subterranean burial chamber in Saqqara that became known by its Greek name — the Serapeum. Because only one Apis bull lived at a time, when one died it was ceremoniously put to rest in the Serapeum by being mummified and interred in a sarcophagus. The pharaohs who ruled when an Apis bull died usually left an inscription on the bull’s sarcophagus. Cambyses left an inscription on the sarcophagus and dedicated an epitaph to the bull he supposedly murdered. Those would hardly be the actions of a murderous madman.

Darius the Tolerant

Darius I earned his moniker “the Great,” not because of his military prowess but due to his political policies that kept the Achaemenid Empire intact. The social and political policies that Darius pursued throughout the empire can be viewed in many temples, institutions, and building projects in Egypt. The Achaemenid Persian culture can be described as eclectic in many ways. The Persians imported materials, workers, and their own styles to build their palaces in Persepolis and Susa. The result was visible Egyptian, Greek, and Mesopotamian architectural influences, demonstrating a truly eclectic style. The Persian eclectic architectural style was extended to their rule over non-Persians.

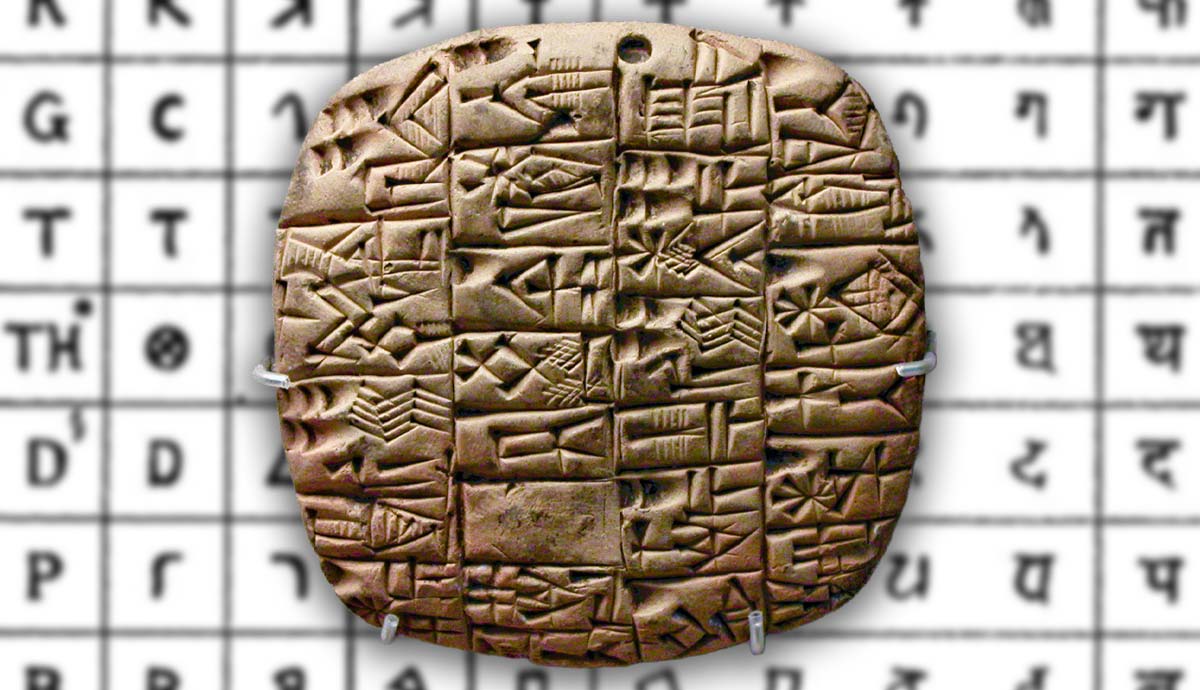

The Persians routinely portrayed themselves as legitimate rulers in the lands they conquered beginning with Cyrus’ conquest of Babylon. After the conquest, Cyrus commissioned the event to be commemorated on the Akkadian-cuneiform Cyrus Cylinder. Cyrus claimed that he restored the Babylonian cults that were ignored by Nabonidus (ruled 555-539 BCE), the last Neo-Babylonian ruler. This can be compared to how Cambyses restored the Neith cult in Sais and how Darius later did similar actions throughout Egypt. Ultimately, the Persians worked to be accepted by non-Persian elites, allowing them to keep power to a certain extent. They did, though, require taxes and fighting men if need be.

Darius followed Cambyses’ lead by patronizing the Apis cult, which is indicated by an epitaph stela from year four of his rule. The epitaph stela indicates that an Apis bull died during Darius’ reign — only one existed at a time — and the Persian king ensured another was installed. Darius’ appeals to Egyptian religious sentiments were emblematic of Persian attempts to win over the Egyptian elites. Darius made other outward gestures of acceptance as well.

The el-Kharga oasis is located about 150 miles west of Thebes (modern Luxor) in the middle of the Western Desert. El-Kharga was not known for much other than a modest sized temple that was built during the Twenty-sixth dynasty and dedicated to the god Amen-Ra. After the Persians conquered Egypt, Darius took an interest in the oasis and its temple, which is today known as the Hibis Temple. The Persian ruler coopted the construction, leaving his name in cartouches and taking credit for the temple dedicated to one of Egypt’s most important gods.

The Original Suez Canal

More than 2,000 years before the Suez Canal of today became a reality, ancient peoples connected the Red and Mediterranean seas via canals. It is possible that the Egyptian King Ramesses II (ruled c. 1290-1224 BCE) oversaw the construction of the first canal. The first documented canal, though, according to Herodotus and the first century BCE Greek historian, Diodorus Siculus, was completed much later.

According to these ancient writers, the canal was initiated by King Nekau II (ruled 610-595 BCE) but completed during the reign of Darius I. The claim is corroborated by three badly damaged hieroglyphic stelae that were discovered in the 1800s. The stelae were likely placed along the route of the canal. The route of the canal went from the Red Sea to the Bitter Lakes before going west to the Pelusiac branch of the Nile River.

The Red Sea stelae demonstrate a number of important aspects of Persian rule in Egypt. First, because they were written in Egyptian they demonstrate a conscious desire by the Persians to be accepted as legitimate rulers of Egypt. The text also praises the Egyptian sun-god, Atum, and positions Darius as the proper pharaoh, who brings life to the people. The completion of the Red Sea canal also indicates that the Persians had long-term plans for Egypt. The canal gave them the ability to more efficiently move goods and people between Persia and Egypt.

Egypt After Darius

The tolerance and attention that Cambyses and Darius I gave to Egypt was not replicated by their successors. The kings after Darius did not rule from Egypt, although Persian influence persisted in Egypt. One of the more interesting aspects of later Persian rule in Egypt was the presence of a sizable Jewish mercenary garrison based in the city of Elephantine/Abu.

It is unknown when the colony began, but it may have predated Persian rule. Egypt had always been a place where different people met and by the late seventh century, foreign trade and mercenary colonies had been established. Modern scholars know about the Jewish colony in Elephantine from a cache of Aramaic language papyri that American journalist and archeologist C.E. Wilbour acquired in 1893. The papyri revealed that the colony was a self-sufficient town complete with a synagogue and an official leader.

Tensions between the Elephantine Jews and the native Egyptians simmered, though, and boiled over during an anti-Persian rebellion from 463-455 BCE. The Jews stayed loyal to the Persians, who they helped to quell the rebellion. The Persians killed Inaros, the leader of the rebellion, but not before the Egyptians killed the Persian satrap. The communal tensions then cooled but were renewed during the rule of Darius II (ruled 424-405 BCE).

In the fourteenth year of the rule of Darius II, a well-organized mob of Egyptians attacked and destroyed the Jewish temple. The reasons for the attack are unclear, but a number of factors likely played a role. Egyptian resentment toward the Jewish mercenaries for supporting the Persians during the rebellion was likely the major factor, but other things should be considered. The insular nature of the Jewish community probably made the Egyptians distrustful of them, which exacerbated cultural differences over mundane things such as dietary restrictions. Whatever the reasons, Persian rule in Egypt would come to a sudden end in 359 BCE. Although the Persians made a brief return to Egypt in 343 BCE, they only produced three kings, who had minimal impact. When Alexander the Great conquered Egypt in 332 BCE, Persian rule was finally replaced with Ptolemaic-Greek rule, but that is another story!