Sculpture was one of the most important art forms in ancient Greece. The materials, techniques, and themes were developed from the first millennium BCE until the Roman times. The Greek sculptors created striking depictions of monsters and fantastical creatures such as sphinxes and gorgons. But their fascination with the human form was what drove the art form. Sculptures of gods, mythological figures, athletes, and individuals are full of admiration for the human body, beauty, harmony, and balance. Ancient Greek sculpture has left a lasting mark on human history. This article explores ten of the most important Greek sculptures that everyone should know.

1. The Kroisos Kouros

At first glance, this statue of a young man, Kroisos, might seem stiff, unnatural, and rigid. However, the significance of this piece lies in the little details, which indicate a transition from the much more limited style of the earlier Archaic period. This sculpture still has some characteristics of the earlier Archaic sculptures of young men, known as “kouros.” It has the same lack of movement. The hands on the sides look lifeless, and the posture is unnatural. Even the facial expression is characteristically Archaic, with a slight smile. But the head is rounder, the muscles are more defined, and the hairstyle is more detailed. The stance is also different. The figure’s weight is slightly shifted onto one leg, which is a step toward a more lifelike and dynamic presentation of the male body.

The Kroisos Kouros, also known as the Anavysos Kouros, dates to around 530 BCE. It was a grave marker for a young man named Kroisos, who was killed in a battle. The statue’s base says: “Stop and mourn beside the monument for Kroisos whom Ares destroyed in the front line.” His family no doubt erected the statue to mourn his loss, but also to commemorate his bravery. This marble statue is 194 cm (6.4 ft) tall.

The Kroisos Kuros was excavated illegally at the beginning of the 20th century. The grave robbers sawed the sculpture in half to make transportation easier. The cutting line can still be seen across the torso.

2. The Charioteer of Delphi

The dating of ancient Greek sculpture can be controversial, and often quite loose years are given on purpose. That is not the case with the Charioteer of Delphi. The dating of this piece can be done with exceptional accuracy. This is because the Charioteer of Delphi was excavated near the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, along with two inscriptions. One includes the name of the dedicator, Polyzalos, who was the tyrant of Gela in Sicily. Inscribed is also the reason for erecting this statue: celebrating a chariot race victory in the Pythian Games at Delphi. These facts allow the rather exact dating of the piece to 478-470 BCE.

The life-size sculpture was originally part of a much larger group. Standing in a chariot, the young man was holding the reins of four horses, now lost. The Charioteer of Delphi might seem beautiful in a rather generic way. Striking but still somehow a bit rigid and cold. A closer look reveals that the sculpture has several details that make it personal. The stance, which first seems to be fully frontal, is, in fact, slightly turned. The head is somewhat looking to the right, and one foot is stepping wider than the other, opening the pose a bit.

The chariot race was among the most esteemed and respected events at the Panhellenic Games. Only aristocrats and the wealthy could afford to own horses and send them to races. The charioteer’s facial expression appears calm and focused, capturing the moment before a race begins. This piece has the power to transport us to the time of the Pythian Games in Delphi over 2,000 years ago.

3. The Discobolus

The Greek concept of “kallos” (κάλλος) refers to the idea of beauty, not only physical but excellence in all areas. In ancient Greece, beauty was highly regarded and considered an essential quality in human character and behavior. Kallos included qualities like moral virtue, harmony, and balance. One way to communicate this idea in art was through the theme of athletes. Greek male athletes from about the 7th century BCE were depicted without clothes, embodying the ideals of athleticism, beauty, and physical excellence.

The Discobolus, also known as the Discus Thrower, perfectly exemplifies this sentiment. It depicts an athlete winding up to throw a discus. The young male is caught in a dynamic and athletic pose that balances the beauty and symmetry of his body with the raw power of his muscles.

The Discobolus is attributed to the sculptor Myron. The piece is known from five main copies, as the original is lost. Of these five, the one in the Terme Museum in Rome is considered closest to the original work. The original was likely created in bronze, not marble, and was made around 450 BCE. Myron is thought to have created sculptures for several athletic heroes. Thanks to the Roman conquerors’ fascination with Greek art, they commissioned numerous copies of the original Greek works. In many cases, this is the only way we can still enjoy many of these works of art today. The above is a Roman copy of the sculpture that has been incorrectly restored, as the original had its head turned backward.

4. Aphrodite of Knidos

The Athenian sculptor Praxiteles is perhaps the most widely recognized as an individual creative artist. Several stylistically very different works are attributed to the artist. Many literary sources describing his works were already circulating in ancient times. Praxiteles’s works include several athletes, divinities, and mythological characters. Many of the works from his extensive career were transported to Rome.

One of the most recognizable examples of Praxiteles’ work is Aphrodite of Knidos. It is known from about 60 copies, fragments, and small-scale versions in marble, terracotta, and bronze, proving how popular this piece was in ancient times. The original was created as a cult object, sculpted in marble, for the Temple of Aphrodite in Knidos, located on the southwest coast of modern-day Turkey. The sculpture remained there until it was sent to Constantinople in 393 CE. It was then soon lost. The full-scale copies are about two meters (6.5 ft) tall and have been found in various places in Italy, Spain, and Greece.

The slightly lowered head of Aphrodite, as she modestly lowers her gaze after being caught during her bath, has been highly influential in how women are depicted in Western art. The voyeuristic roleplay between eroticism and chastity has inspired artists until our day. As the first-ever depiction of a female without covering clothing, the work caused a scandal in the ancient Greek world. This was definitely not the way people were used to seeing Aphrodite.

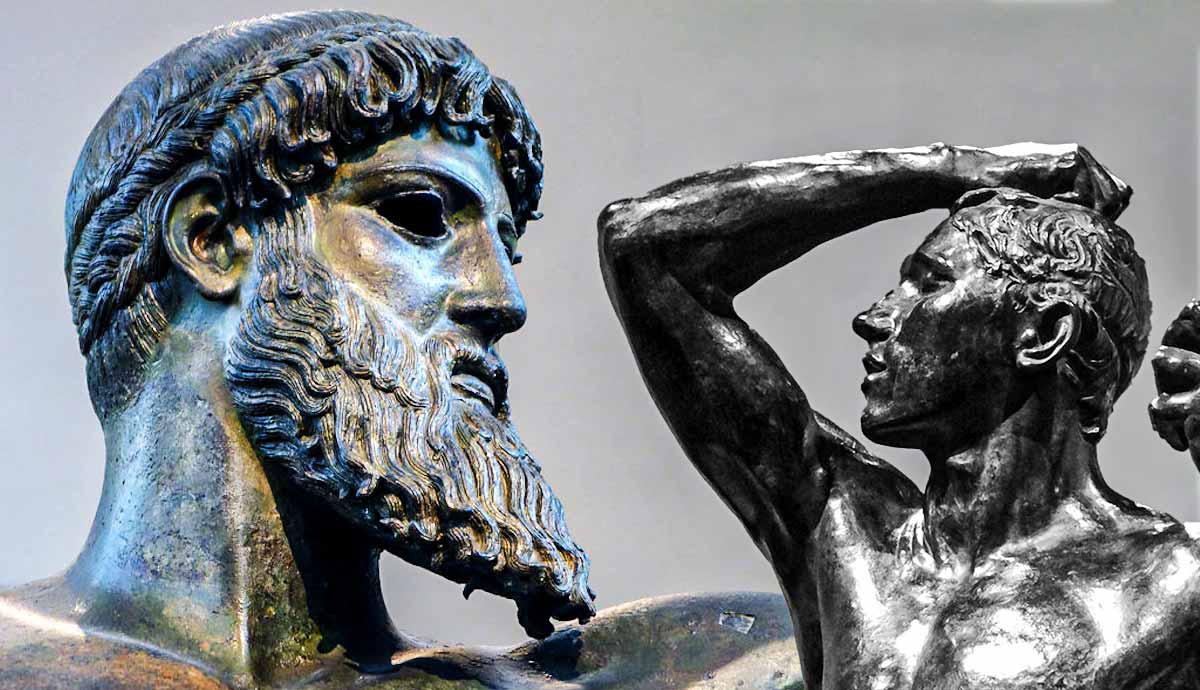

5. The Artemision Bronze

When entering the exhibition hall at the Archaeological Museum of Athens in Greece, the statue of the Artemision Zeus is unmissable. Situated at the center of the hall, its proportions are impressive from every angle. The sculpture is 209 cm (6.10 ft) in height with an arm span of eye-popping 210 cm. The sculptor skillfully portrayed the human anatomy, precisely capturing the muscles and physicality of the male figure. But the symmetry and harmony of the piece are an illusion. Looking more closely, it is evident that the length of the arms in relation to the body is anatomically incorrect. Yet the naturalism and dynamism of the pose are impressive.

The Artemision Zeus dates to 460-450 BCE. It is a testament to the development of bronze sculpture in the Classical period. With its far-reaching, extended pose, this type of sculpture would not have been possible to execute in marble. However, developing the so-called “lost wax technique” in bronze sculpture made creating pieces such as the Artemision Zeus possible. The statue was discovered in 1926 off the coast of Cape Artemision, on the island of Evia in Greece.

Although this article uses the term Artemision Zeus, the sculpture is also known by the name of another god, Poseidon. Why the controversy? Well, the outstretched right arm of the god held an object, but from the hand, it is not entirely clear what. In the case of Zeus, it would have been a thunderbolt, held a bit like a baseball. In the case of Poseidon, the hand would have held a trident. Classical archaeologists and art historians are divided on which explanation is more likely. In either case, the artistic skill level shows the high quality of the statue dedications at ancient Greek temples. The Artemision Zeus gives us a unique glimpse into how art, religion, and culture in Greece were intertwined.

6. Vénus de Milo

The Aphrodite of Melos, or Vénus de Milo, is one of the best-known Greek sculptures. It is also among the most loved in the Louvre Museum’s collection. The Vénus de Milo was found in 1820 on the small Greek island of Melos. There are several reasons why this sculpture is so famous. One of them is the clever marketing by the museum. However, other interesting aspects earned the Vénus de Milo its place as one of the most magnificent Greek sculptures from the Hellenistic era. During the Hellenistic period, Melos was not a significant city-state. Instead, it was a minor, traditional Greek polis. Yet, it could have been at the center of a dynamic change of style in sculpture, as the Vénus de Milo confirms.

The Vénus the Milo combines different styles of sculpture so cleverly that scholars were initially convinced it belonged to the Classical period. But the beautifully executed drapery is definitely Hellenistic. Although even famous sculptors such as Praxiteles sometimes copied works, the Vénus de Milo is an original creation. Interestingly, the sculpture was found inside a Hellenistic Gymnasium. These were places for athletic or military training, but were also educational and cultural institutions where new subjects, such as philosophy, were taught. The feminine Aphrodite is often referred to as the goddess of love, but in the context of the gymnasium, we have a new perspective on how broad her influence and scope were in Hellenistic society.

7. The Barberini Faun

During the Archaic and Classical periods, sculpture was primarily displayed in religious or commemorative settings, such as temples or grave sites. But things changed during the Hellenistic period. Statues began to decorate private spaces, such as homes, gardens, clubhouses, and libraries. There was no need to be timid anymore; daring, even shocking topics, became popular. Eros, the god of sexual love, is known from several pieces.

This is obvious in the case of Aphrodite. Depictions of Aphrodite during the Classical period preferred to emphasize the goddess’s virtuosity. But in the case of the Aphrodite of Knidos, we see the goddess in a completely new perspective, something that would have been unthinkable before. We know satyrs as wild animal-like creatures who accompany Dionysos in wild parties. In vase paintings, they engage in all kinds of sexual escapades. But there is something new with the Barberini Faun, a sculpture of a drunken satyr sleeping. It is openly sexual, even vulgar. The piece is from the second century BCE and is currently in Münich.

The sculpture was found in Rome in 1620 and was badly damaged, missing the right leg and part of the head. Although male nudity was nothing new in Greek art, the up-front sexuality of the pose was something not seen before. The pose of the satyr, lying in oblivion, straightforwardly invites the viewer to the role of the voyeur.

8. The Laocoon Group

Roman writer and historian Pliny the Elder describes seeing a sculpture at the palace of Emperor Titus that was superior to anything he had seen before. The statue was of the mythological figure Laocoon, a Trojan priest, and his two sons struggling in the grip of snakes. In 1506, a fantastic marble group was discovered close to the place that Pliny described. The masterpiece, created by three Rhodian sculptors, immediately had an incredible effect on Renaissance artists. In fact, Michelangelo was present when the Laocoon Group was unearthed.

The Laocoon Group showcases incredible mastery in capturing extreme emotion, provoking movement, and representing detailed human anatomy. The intertwined bodies of Laocoon and his sons convey a sense of agony and despair, which continues in their facial expressions. The sculpture tells the whole story of their struggles. There is debate whether the Laocoon Group was sculpted by Greek sculptors in Rhodes or if the sculptors were residing in Italy. But the style is undoubtedly Hellenistic.

The widespread fascination with the Laocoon Group lies not only in its artistic merits. The Laocoon Group earned its place as one of the most celebrated and studied ancient Greek sculptures in art history because it has been accessible to visitors for centuries. As part of their “Grand Tours” in the 17th and 18th centuries, numerous Europeans had the opportunity to see it. The Laocoon Group inspired countless great writers, painters, sculptors, and other artists.

9. Nike of Samothrace

In ancient Greek art, the goddess of Victory, Nike, usually stayed close to goddess Athena. But in the case of the Nike of Samothrace, she is shown majestically alone. The sculpture is also known as the Winged Victory of Samothrace, describing the ethos of the moment the sculpture was created to commemorate. The sculpture shows Nike, who has just landed gracefully with wings still in mid-air, on the deck of a ship to announce a victory. The goddess is wearing a draping long belted himation dress with the fabric clinging around her body. The effect is both sensual and dramatic.

The sculpture of Nike is 275 cm (9 ft) tall, and together with the base, it is over 550 cm (18 ft) tall. It was discovered in 1863 on the island of Samothrace in the Northern Aegean Sea. Stylistically, the dating of the sculpture is problematic because it mixes traditional elements with newer ones. During the middle of the 2nd century BCE, a revival of classicism became typical in sculpture and Hellenistic art in general. The Nike of Samothrace is likely from around 200-190 BCE.

The statue is currently displayed at the Louvre in Paris, where it greets millions of visitors at the top of the main staircase. As part of the request to repatriate several culturally significant monuments, the Greek government has also requested the return of the Nike of Samothrace to Greece, but so far, in vain. The Athenians are left to admire a copy of the original in one of the busiest metro stations in the city.

10. The Boxer at Rest

The development of Greek art was deeply linked to religion from the Early Iron Age until the end of the Classical period in the 4th century BCE. However, when approaching the so-called Hellenistic period, the roles of gods and goddesses were often replaced by monarchs, mighty kings, and emperors. Through the expansion of the Greek world, led by Alexander the Great, new cultural influences replaced the old ones. As monarchs were now patrons of the arts, they became the focus of artistic production.

The Boxer at Rest, also known as the Terme Boxer or Boxer of the Quirinal, is a bronze sculpture dating to around the 4th or 3rd century BCE. It was discovered in 1885 during construction works near the Baths of Constantine on the Quirinal Hill in Rome, Italy. The statue is currently displayed at the Terme Museum in Rome.

The Boxer at Rest is a life-size representation of a weary and wounded boxer. He is seated, looking slightly up as if asking for mercy. His exhaustion and suffering are shown with incredible realism. He has a battered face and swollen ears and is covered in bruises. Along with his physical wounds, his psychological torture is clearly presented. Although muscular and powerful, he is also vulnerable. This was the complete opposite of the idealized beauty of the earlier athletic sculptures. It was likely created for a dramatic purpose, and even today, this piece can still provoke deep emotions.