The Olympic games date back to 776 BCE, when the first games were held in Olympia, Greece. Athletic events were organized in a four-year fixed cycle in also Nemea, Delphi, Isthmia, and Athens. All games included similar sports. For example, during ancient times, discus, javelin, and wrestling were already part of the athletic program. But did you know there was also a free-fighting event that could end with the opponent’s death? And why was a male beauty contest considered an athletic event? Here are six lesser-known sports from the ancient games.

1. Pankration — No Holds Barred

Very few rules, all holds allowed, and no time limit. Pankration, a heavy combat sport, was a mix between boxing and wrestling. The word pankration derives from the Greek words pan, which means all, and kration, which means power. So literally, with all might.

Fought in a boxing ring, the battle ended only with the total submission of the opponent. The only things forbidden were pushing a finger to the opponent’s eye and kicking the groin. Choking, breaking bones, strangling, and punching simultaneously were part of the game. Kicking was an essential method of trying to win in pankration.

There were three so-called heavy sports in ancient games. These were boxing, wrestling, and pankration. Pankration was introduced to the games in 648 BCE. The ancient audience certainly had a higher tolerance for violence, which they probably just found entertaining. Pankration was a sport where the line between sport and assault was blurred. But despite pankration being obviously incredibly dangerous and violent, very few deaths were recorded. In Athens, an accidental killing of an opponent during an athletic event was considered an unintentional homicide. A pankratiast who ended up dead after the game was simply described as a victim of bad luck.

2. Hoplitodromos — Running With a Full Armor

The ability to run fast was an essential survival skill in warfare and hunting. The earliest evidence of running competitions in Greek art dates back to about 1300 BCE. Homer describes races in his epics, one of which was won by Odysseus. Running was the first sport at the Olympic games and the only event for the first 13 events, from 776 BCE to 728 BCE. Even when other competitions were added to the Olympic program, running remained a sport favored by the audience.

The hoplitodromos was added to the game program relatively late, from the 65th Olympiad onwards. The event was the last running event to be added to the game program. The race required the runners to wear full hopla, the equipment of an infantryman. This included a bronze helmet, greaves, and a heavy, round shield. The total weight of the armor was over 13 pounds or about six kilos. The competitors ran the length of two stades, which means two lengths of the track.

From 450 BCE onwards, the race was organized without the greaves and helmets, but the shield remained an essential part of the race. Running while holding a large shield with the left hand required strength, balance, and flexibility.

3. Long Jump — With Weights and Flute Music

Music, dance, and physical exercise were the basic elements of education for boys in ancient Greece. Youths of Athens spent much of their time in gymnasia, where they practiced sports, dance, and music. Body exercise was considered important, but so were singing and dancing. The body, however, had an overriding value in ancient Greek thinking. The body needed to be trained systematically from a very young age to achieve the best possible development.

Music and dance were not linked with exercise just for the beauty of it. Music gave movements harmony and rhythm, which was necessary for the practice. In many of the images in ancient art, athletes are portrayed together with an aulos-flute player. Flute music also accompanied sports at competitions. In ancient games, the long jump was one of the sports organized with music. The flute melody was likely used to help athletes with the rhythm and keep time. The jumpers had a pre-set time in which they had to make a series of five jumps.

Long jumpers had hand-held stone weights to assist their performance. Whether this was meant to help them jump longer or help them balance better during the landing is debatable. Different sizes of these weights have been found in archaeological excavations, ranging from 3 to 13 pounds or 1,5 to 6 kilos.

How long did the ancient athletes jump? Unfortunately, no exact results are known. Exaggerating and creating myths about the achievements of athletes were the norm, so truthful numbers are hard to find.

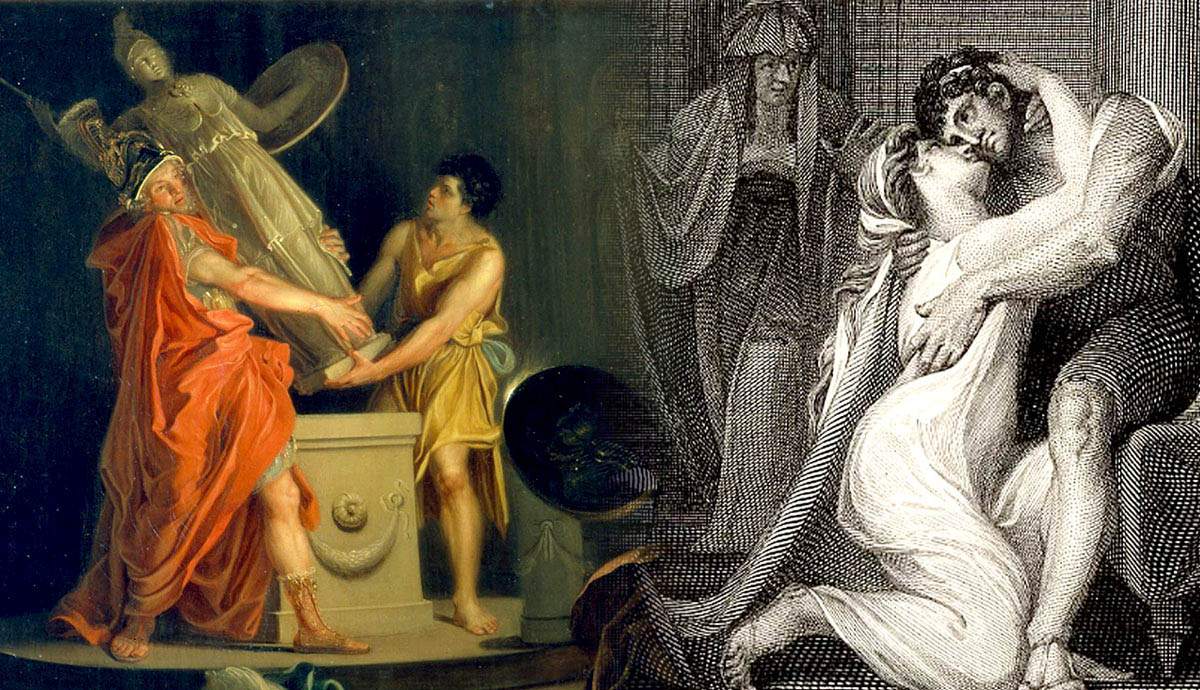

4. Lampadedromia — Torch Race to Light the Fire at the Altar

The Panathenaea was the most significant festival in ancient Athens. Panathenaea had a strong religious character, as it was organized to honor the city’s patron goddess, Athena. The whole city participated in the events and the massive theatrical progression, which led to the top of the Acropolis. Athletes from all over the Greek world came to compete in the games. Because the event was so big, we have much knowledge about Panathenaea. Ancient writers, as well as vase painters, have created an abundant amount of depictions of the games.

The athletic events at the Panathenaea were divided into two groups. The first group consisted of the Olympic program, where all Greek athletes could compete, just like in the other panhellenic games. The second category included events with a more religious or military character. Only Athenians were allowed to take part in these games.

One such event with a strong religious link was a relay run, with burning torches instead of batons. The race began from the altar of Prometheus in the gymnasium of the Academy, the area now known as the Akademia Platonos in Athens. The 1,5 miles or about 2,5 km course ended at the heights of the Acropolis. The winner was the one who was first to light the sacrificial fire on the great altar of Athena. Later some variations of the race took place, and the relay was turned into an individual competition instead of a race between tribes. Nocturnal horse races with torches also became very popular.

5. Euandria — The Male Beauty Contest

There is a deeply rooted spirit of competition amongst the Greeks. According to the myth, when Achilles was set to go to the Trojan war, his father Peleus told him: “Always be the best and excel over others”. There are numerous times in Greek mythology when heroes strived to be the best. Male beauty was much prized in ancient Greece. Possessing a beautiful and healthy physical body signified something good, pure, and noble. Because war and conflict were so common, most Greek male citizens could expect to be called on to fight during their life. Caring for the body was considered both a social and a political obligation. And showing it off meant that one took pride in keeping fit for the fight.

Euandria was a competition held at the Panathenaia in Athens, as well as in other cities. Even though it was essentially a competition where men were judged based on their appearance, it was athletic in nature. The contestants had to show not only their physical beauty but also demonstrate the strength and size of their frames. Although the winners of euandria are listed among the athletic winners, the competition’s criteria are not entirely clear. It might have been close to a modern-day bodybuilding competition, where competitors are judged based on the definition, symmetry, and balance of their muscles. In ancient times, as today, this would have required athletic training and a good diet.

Winners of the male beauty contests have been recorded as receiving weapons as prizes. They were invited to lead a procession to the temple, where they received a myrtle crown, like the athletic game winners. In Athens, the winner even received an ox, a very expensive prize.

6. Aphippou — Acrobatic Race on a Chariot

Equestrian events and horse races were an essential part of athletic competitions. We know there were horse riding races and chariot races with either two or four horses from very early on. Horse events were very popular with the audience. New equestrian events were added to the program regularly. By the 2nd century BCE, there were sometimes as many as 28 different horse events during the games.

Few have heard about apobate, a competition for two men, a horse, and a chariot. Apobate was a competition where one of the men dismounted the chariot at full speed, ran behind it for a given length, and then remounted the fast-moving chariot again. Despite a lot of the art showing the contestants naked, the participants actually wore armor. The runner and the chariot driver were both held in high esteem and awarded separately. The efforts of the horses were also noted. Only the best men could compete in this sport, where accidents were apparently quite common.

Horse races in ancient times, like today, were an expensive sport. Horses were symbols of nobility. They were tenderly taken care of and regularly given names. Because only a few elite members had the means to sponsor horse events, apobate and other horse races had an aristocratic nature. Only the wealthiest could own horses, train them and keep them well-fed in the stables. Apobate was created to imitate events on the battlefield. Maybe the sport appealed greatly to those in the audience who had actual experience of taking part in war themselves.

Sources:

Nigel B. Crowther: Male Beauty Contests in Greece: The Euandria and Euexia. L’Antiquité Classique, 1985, T. 54 (1985), pp. 285-291 Published by: L’Antiquité Classique Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41657172

Nigel B. Crowther: Euexia, Eutaxia, Philoponia: Three Contests of the Greek Gymnasium. Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik , 1991, Bd. 85 (1991), pp. 301-304 Published by: Dr. Rudolf Habelt GmbH Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20187430

Manuela Mari, Paola Stirpe: the Greek Crown Games. In the Oxford Handbook Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World, 2021.

Nigel Nicholson: Greek Hippic Contests. In the Oxford Handbook Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World, 2021.

Michael B. Poliakoff: Greek Combat Sport and the Borders of Athletics, Violence, and Civilization. In the Oxford Handbook Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World, 2021.

Julia L. Shear: The Panathenaia and Local Festivals. In the Oxford Handbook Sport and Spectacle in the Ancient World, 2021.

Nancy B. Reed: A Chariot Race for Athens’ Finest: The “Apobates” Contest Re-Examined. Journal of Sport History , Winter, 1990, Vol. 17, No. 3 (Winter, 1990), pp. 306- 317 Published by: University of Illinois Press Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43609193.

Panos Valavanis: Games and Sanctuaries in Ancient Greece. Kapon Editions, 2017.

David Phillips, David Pritchard. Sport and Festival in the Ancient Greek World. The Classical Press of Wales, 2003.

Ian Jenkins: Defining Beauty – The Body in Ancient Greek Art. The British Museum, 2015.

David Potter: The Victor’s Crown – A History of Ancient Sport from Homer to Byzantium. Quercus, 2011.

Nicolaos Yalouris: Athletics in Ancient Greece. George A. Christopoulos, 1976.