Despite her all-too-brief life, Annelies “Anne” Frank is the stuff of legend, lore, and countless heart-felt tributes. She is the unspeakably tragic face of the Jewish Holocaust. Her family’s temporary refuge in their Amsterdam “secret annex” is among the most revered global visitor sites. And all this for a self-described “chatterbox” who in many ways might have been a typical teenager, now or then. She never lived to see her 16th birthday, suffering the same horrific fate as an estimated three million of her fellow Jews in Hitler’s death camps.

Anne Frank’s Notes From the Underground

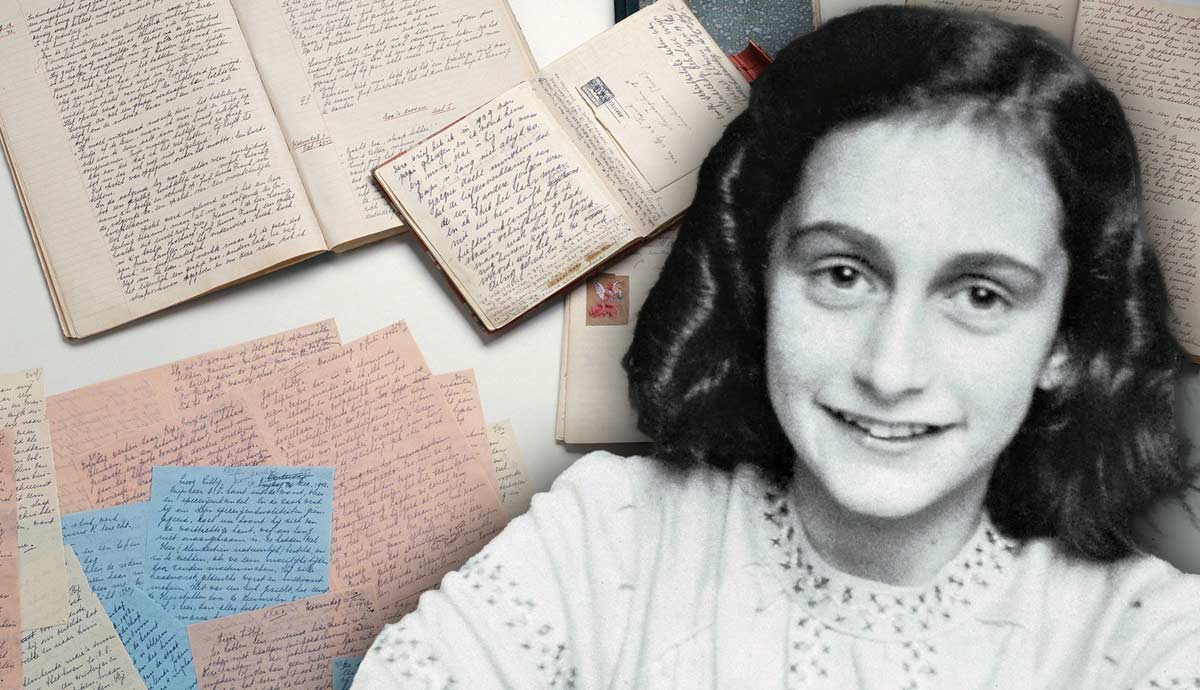

How little did Anne know that the blank diary she received as a gift on her 13th birthday in July 1942 would not only become an extraordinary historic artifact but also an intensely personal record of a young woman attempting to survive—and simply grow up—under the dreadful circumstances of stealth wartime captivity. Each day was a struggle against tedium, boredom, fear, anxiety, hunger, privation, and indignity, all against the constant threat of Gestapo arrest and merciless deportation to Auschwitz that might come banging at the door any day or night.

To escape Hitler’s preliminary rounds of anti-Semitic genocide, Anne’s family moved from Frankfurt, Germany, to Amsterdam in 1933. She grew up bright, popular, and cheeky. She loved to read perhaps more than anything, especially history. She hated math. She had oodles of friends, including boys. It’s obvious that she wanted to become a writer of some sort. While she’s most celebrated for her diary, first published in 1947, she also penned fairy tales, poems, and short stories.

In her entries, especially at the beginning, she can be brazenly and impetuously candid when dishing on her classmates, as catty as any kid today. She calls one boy a “sniveling, obnoxious little goof” and another “a real brat.” In the contemporary editions, Anne is fond of surprisingly ripe revelations in censorious sexual matters, passages omitted in the early editions (supervised by Anne’s surviving father). Regarding one “terrific” but dirty-minded boy, rumor has it that—pssst!—he’s “gone all the way.”

Anne’s light, gossipy tone early on makes the looming background drama that much more ironic, if not cruelly and existentially absurd. Knowing how the saga of Anne and her extended annex “family” turns out is heartbreaking. One can’t help but sense Anne’s joyful anticipation after they hear the stirring news of the 1944 Allied D-Day invasion from BBC radio. “Is this really the beginning of the long-awaited liberation?” she asks, followed by her forlorn hope that “maybe I can go back to school in September or October.” All her entries are addressed to dear “Kitty,” the imagined best friend she feels safe confiding in. Irony drips like tears from each page, starting with her humble presumption that “It seems to me that later on neither I nor anyone else will be interested in the musings of a thirteen-year-old schoolgirl. Oh well, it doesn’t matter.”

The Annex

So who was this Frank family and where exactly did they hide? Along with Anne, there is her beloved father Otto, mother Edith, and Margot, the eldest teen daughter. Stymied in his repeated efforts to emigrate with his family to the USA, on July 6, 1942, Otto chose to ingeniously secret his family in a two-floor annex behind the building that housed the spice and jam companies he had formerly managed. This came at a time when Nazi occupiers—working with Dutch police collaborators—had begun their arrests and deportations of Holland’s Jews. Behind a moveable bookcase camouflaging the entry, the Franks lived—ever so quietly—on those two small upper floors topped by an attic.

They were soon joined by Otto’s work associate Hermann van Pels, his wife Auguste, and their teenage son Peter. In November 1942, they accepted one more tenant, Fritz Pfeffer, a dentist whose arrival is met by Anne with a gleeful anticipation that slowly dissipates, like air from a party balloon. It’s a bit confusing, but when Anne wrote her diary she used pseudonyms for the Annex residents, so that, for example, Fritz Pfeffer became “Albert Dussel.” By whatever name, Anne comes to barely tolerate the bathroom-hogging, food-hoarding Dussel, who first (oddly) displaces Margot from the sisters’ tiny bedroom, confining an adolescent Anne with a wheezy, middle-aged, kvetching roommate.

Perhaps understandably, while Anne is memorialized as the heroine of her own story, popular accounts commonly rarely give enough credit to the various “helpers” who enabled the fugitives to survive so long, and at great risk to themselves. It’s a lesser-known fact that other (non-Jewish) workers at Otto Frank’s companies stayed on and went about the business day, selflessly running errands and bringing in food, books, and other provisions for the Franks and their companions. At the top of the unsung brave were two young Dutch women, Miep Gies and “Bep” Voskuijl, as well as Johannes Kleiman and Victor Kugler (who helped build the trick bookcase). Both men were arrested when the annex was breached on August 4, 1944, but both miraculously managed to evade time in a Nazi forced labor camp.

The Daily Grind

In her weekly, sometimes daily, confessional entries, Anne chronicled the two-plus years she spent in the annex, encompassing events ranging from the sublime to the ridiculous that, in turn, trigger a cascade of feelings in the young, rather frail, and uber-sensitive author. They trace the mercurial changes and maturation of a young woman forced to live in circumstances that would test—and perhaps break—most of us today. Yet despite her horrendous situation, she almost always finds a way to escape despair and gloom, usually with self-effacing or sarcastic humor. After one barely edible meal she exclaims, “If you’re trying to diet, the annex is the place to be!”

Many of Anne’s entries fall straight from the timeless generation gap between young and old that has crossed humankind for eons. From her words alone, she was a willful, brash, opinionated girl with a lot on her mind, thus her famous diary. While she was close to her father, her relations with the three other adults were prickly, including her own mother; modern parents may experience their own keen feelings of déjà vu when Anne puts the blame on Mom for not “understanding” her.

Perhaps the most interesting (and most natural) relationship that develops is between Anne and Peter. When he first arrives, Anne dismisses him as a “shy, awkward boy.” But her feelings begin to change in early 1944. They begin chatting and spending time together, even in his tiny room with the door closed. According to Anne, nothing untoward ever happens, though her parents aren’t quite sure of that. Peter, in fact, is shy but he also has clever things to say. Both are curious about sex and Peter one day points out that one of the cats (Mouschi) roaming the floors is demonstrably a tom. Anne complains that her parents hardly told her anything about those strange and inconvenient “facts of life,” especially not her mother, proving that some teenage gripes are indeed ageless.

While by day Anne and company were holed up in the annex, at night and on weekends they usually could creep down to the offices below to use the large kitchen, take a rare bath, or listen to the radio together. The newscasts from the BBC were a lifeline, and Netherlands’ exiled Queen Wilhelmina offered nightly notes of patriotic inspiration. Nevertheless, downstairs was also a source of great anxiety, especially since burglars broke in repeatedly to create all sorts of noise and havoc that once sounded like they were near the bookcase. That ancient warning of “familiarity breeds contempt” comes to mind when Anne recounts the spats, arguments, and tensions that couldn’t help but flare among eight people cooped up 24/7 in such close quarters and in such dire circumstances. Anne fortunately had one temporary escape, and that was her trips to the front attic (sometimes with Peter) that allowed her to behold the sky.

Anne’s Living Testament

Anne and her family weren’t devout Jews, but she prayed to God and certainly was a spiritually-minded individual. Some would call her a pantheist in seeing and sensing God and the divine in nature. If her girlish exasperations give away her age, she is also blessed with lyrical epiphanies that leap out and transcend the page. One day in February 1944, she writes in a P.S. (“to Peter”), “Whenever you are feeling lonely or sad, try going to the loft on a beautiful day and looking outside. Not out the houses and the rooftops, but at the sky. As long as you can look fearlessly at the sky, you’ll know you’re pure within and will find happiness once more.”

Anne’s diaries, which eventually comprised several handwritten books, have a complicated provenance. In a March 1944 radio broadcast, an exiled Dutch minister suggested that those still on the home-front should preserve written records of their wartime ordeals for posterity. With that cue, Anne returned to her earlier entries and revised and sometimes annotated them, resulting in a version actually longer than the one released to popular acclaim in 1952, titled The Diary of a Young Girl, which Otto Frank had authorized.

In 1991, however, a longer “definitive” version was published, which essentially re-inserted those entries Anne and then her father had excised (primarily owing to content both thought either unkind or too intimate). The critical new edition was at least partially prompted by spurious and hateful allegations by Holocaust deniers who claimed the diaries weren’t authentic.

The Death of Anne Frank

Even those who have never read Anne’s diary likely know how her story tragically and obscenely ended. Following the arrest of the annex eight in August 1944, they were first sent to a transfer camp in Holland and then put on a train to the monstrous Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camps in German-occupied Poland. All suffered the worst of Nazi horrors, and most died there, along with millions of other victims of the so-called Third Reich.

Only Anne’s father lived, surviving to see the camp liberated by Russian troops in January 1945. One year before, Anne and her sister had been transported to the Bergen-Belsen camp in Germany. Amid their further miseries and degradation, Anne at least discovered that one Amsterdam friend, Hannah Goslar, was at the camp too. They were both heartened by their reunion, even if they could not see each other through the barbed-wire fence separating them.

In the middle of that dreadfully cold winter, the sick and emaciated prisoners overflowing Bergen-Belsen were left to suffer slow, agonizing, lice-infested deaths, whether from malnutrition and simple exhaustion to typhus and other wretched diseases. Anne and Margot died there sometime in March 1945. It was only a month or so before the camp was liberated by British troops.