summary

- Political Match: Henry VIII’s marriage to Anne of Cleves was driven by Cromwell’s desire for a Protestant alliance.

- Awkward Meeting: Henry disliked Anne after their first meeting, where she didn’t recognize him in disguise.

- Amiable Annulment: Anne’s acceptance of the annulment secured her a comfortable life and status.

- Cromwell’s Downfall: While Anne survived, Thomas Cromwell was executed due to the king’s dissatisfaction with the marriage.

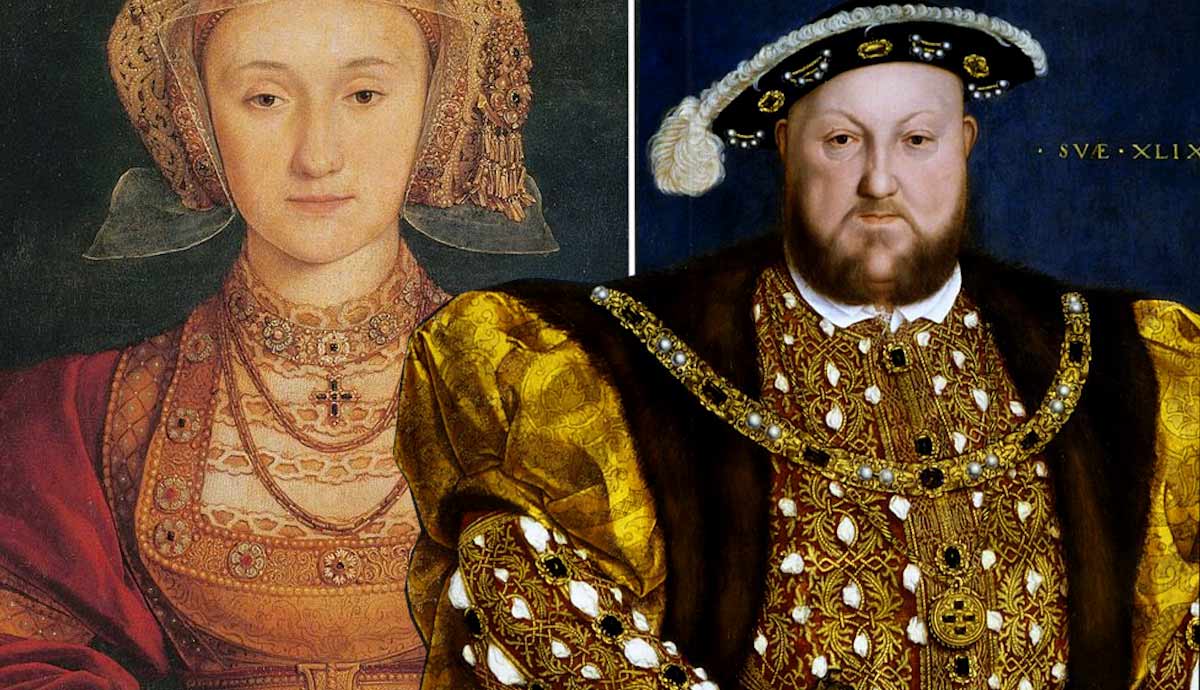

The annulled marriage of King Henry VIII to Anne of Cleves has become known as the marriage that ended because Anne was too ugly for Henry. But this narrative glosses over the true circumstances of a politically motivated marriage, which was successful in some ways despite its brevity.

Heir and a Spare

Anne of Cleves was Henry VIII’s fourth wife. Henry’s third wife, Jane Seymour, is generally considered his greatest love and also gave him the greatest thing of all: a son. Edward Tudor was born on the 12th of October 1537, finally giving Henry an heir. Sadly, 12 days after Edward was born, Jane died due to childbirth complications. While Henry was devastated by the loss, he needed a new wife, as every heir needs a “spare.”

The Search for a Match

Anne of Cleves was not Henry’s first choice for wife number four. Henry sent his court painter, Hans Holbein the Younger, across Europe to paint eligible princesses. He set his sights on Christina of Denmark, but she was not in favor of the match, and reportedly said, “If I had two heads, I would happily put one at the disposal of the King of England.” It seemed that Henry’s beheading of his former queen Anne Boleyn was frightening the princesses of Europe off. Thomas Wriothesley, the English diplomat in Brussels, advised Henry to “fix his most noble stomach in some such other place.”

It was Thomas Cromwell, Henry’s chief minister and right-hand man, who turned Henry’s attention in a new direction. Cromwell’s search for a new queen of England had a pressing political motivation. Overseas, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and Francis I of France seemed to be getting along better than usual, which was bad news for England. Cromwell knew that England needed support in case the worst happened, and the new enemies-turned-allies Charles and Francis decided to wage war on England, their mutual enemy.

Choosing Anne of Cleves

Thomas Cromwell sought out Protestant allies who could help England if they found themselves at war. Cromwell suggested that Henry consider the daughters of the Duke of Cleves, Anne and Amelia. The Duke of Cleves had previously stood up to the Holy Roman Empire, making him a logical and strong ally for England.

Henry sent an ambassador to Germany to see Anne and her sister Amelia and discuss the terms of a proposed marriage. The report from diplomat Christopher Mont was positive enough to convince Henry to send Holbein to paint the two daughters for Henry to see. Henry heard accounts of their beauty, but he wanted to make up his own mind.

Whether Cromwell instructed Mont to talk highly of the daughters’ beauty and promote the idea of an alliance with the Cleves family is debated. Henry was presented with Holbein’s portraits and was enamored with Anne. No time was wasted, and plans for the marriage were set in motion. The final agreed-upon details were written up in a treaty, which was signed on October 4th, 1539.

Anne Arrives in England

Anne was now sent to her new home, a strange and foreign land where she did not speak the language. She had a long and tumultuous journey to England, but she finally arrived in Deal, Kent, on the 27th of December 1539. Anne journeyed through England towards London and was expecting to meet Henry on January 3rd. On January 1st, she was resting at Rochester Castle when she received some unexpected visitors.

Henry had arrived early at Rochester Castle to surprise Anne. There was a chivalric tradition popular in elite circles where a princess has an unexpected meeting with a young man whom she instantly falls in love with, only for her to discover later that he was really a prince in disguise. Henry appeared in Anne’s room, wearing a cloak and mask to disguise himself. Anne was alone, quietly looking out of her window, when suddenly Henry approached her and gave her a kiss.

Anne, who was not familiar with this tradition, did not realize it was her betrothed in disguise. Naturally, she did not react well to the masked stranger kissing her in her room. She said nothing and turned away from her admirer in a state of embarrassment. Henry, who believed he was a handsome man, was mortified at Anne’s rejection. Did she not recognize a king when she saw one? Clearly, their love was not meant to be.

Henry hastily left to change into his regal attire and returned to Anne’s room. She recognized him this time and was respectful and courteous towards him. Unfortunately, the damage was done. Henry’s ego was hurt, and this could not be undone. He left the room and is said to have proclaimed, “I like her not.”

Cold Feet

Henry pleaded with Thomas Cromwell to find a way out of the marriage. He tried to blame Anne’s appearance for his dissatisfaction, claiming she was “nothing as well as she was spoken of.” There is no record of anyone saying anything negative about Anne’s appearance before this, and Henry himself reportedly admitted that she was “well and seemly.” Henry was probably motivated by embarrassment over their first meeting and needed to turn the narrative around on Anne.

Despite the pressure on Cromwell to get Henry out of the marriage, there was no way to call off the wedding without offending Anne’s brother, the Duke of Jülich-Cleves-Berg, which could result in retaliatory conflict. Cromwell found no solution, and the wedding went ahead.

Henry and Anne were married on the 6th of January 1540 at the Royal Palace of Placentia in Greenwich. It is reported that Henry said to Cromwell on the way to the chapel, “If it were not to satisfy the world and my realm, I would not do that I must do this day for none earthly thing.” The day ended and the newlyweds retired to their bed chamber.

Ditching Anne of Cleves

Henry was very open in his retelling of events in the bedroom with his new queen. The problem was a lack of events occurring at all. Henry tried for several nights to consummate the marriage, but to no avail. Again, the blame for this was placed entirely on Anne’s shoulders. Henry could not possibly be the reason for the lack of success, despite being twice Anne’s age and riddled with health problems that probably caused unpleasant odors. It became clear that the union would not last.

In March 1539, Anne received a new lady in her household named Catherine Howard. When Henry first set his eyes on her, the impetus to get rid of Anne gained new momentum.

Henry was not discreet when it came to his feelings toward Catherine, with Anne herself noticing his attraction to her. His ministers knew that they needed to free him from his marriage to Anne as quickly and as gracefully as possible; Henry wasn’t one to wait patiently, and the longer he had to endure the situation, the angrier he would get.

The Annulment

Then, on the 24th of June 1540, Anne was sent to Richmond Palace in Surrey. Henry told her there were concerns about the plague in the city, and it was recommended that she leave Westminster and retreat to the much more rural Richmond. There was promise of Henry joining Anne there soon after, but the royal couple were not to see each other as husband and wife again.

Considering that we know Henry himself was terrified of illness, had there been any actual threat of plague, Henry would not have stayed in London. Unsurprisingly, on the 6th of July, Anne was informed of Henry’s intentions to annul their marriage. Anne accepted the annulment without much fuss, which was the smartest thing she could have done. We can never know how Anne truly felt about Henry, and if she was sad or relieved when their attempt at a marriage ended. However, the way she responded ensured her safety and comfort for the rest of her life, which was a better fate than some of his other wives.

On the 12th of July 1540, the official announcement was made that the marriage of Anne of Cleves and Henry VIII had been annulled. Henry was not one to waste time, and was married to Catherine Howard on the 28th of July 1540.

The Settlement

As Anne was amenable during the annulment process, Henry was very generous and kind toward her in the years that followed, perhaps as a way of showing his gratitude for Anne’s acceptance of the annulment and making things a lot easier for him than they had been before.

Anne received a lavish settlement that included Richmond Palace and Hever Castle, former residence of the Boleyns. She also earned herself the moniker of the “King’s Beloved Sister.” She held rank above all the women in England, excluding Henry’s daughters and any future wives.

Considering the bitter ends that the rest of his wives met, Anne’s life was considerably better. She was often invited to court and maintained pleasant relations with Henry. The sad irony was that for Catherine Howard, her marriage to Henry very quickly deteriorated, and she became a victim of Henry’s axe on February 13th, 1541.

Retribution

Henry was not just going to let things go and move on graciously. He felt that he had been poorly advised to pursue the ultimately embarrassing marriage with Anne. Soon, the finger of blame was pointing at Cromwell. The situation was made worse by the fact that the feared alliance between Charles V and Francis I failed to materialize, undermining the reason for the alliance. Consequently, Cromwell had put the king through a humiliating ordeal for nothing. Others involved in the marriage negotiation, such as Thomas Wriothesley, exploited Cromwell’s weakened status to make him their scapegoat.

On the 10th of June 1540, Cromwell was arrested in Westminster. His execution was delayed by Henry until his annulment to Anne was complete, but Cromwell was publicly executed on Tower Hill on the 28th of July 1540. Meanwhile, Henry was happily enjoying his wedding day to Catherine Howard.

Anne of Cleves’ Legacy

While history likes to remember Anne of Cleves as the “ugly wife,” there was much more to her than meets the eye. Probably the most successful bride of Henry’s, she was the longest surviving of all his wives and lived for 10 years after Henry’s death. She maintained favor with the Tudors and was even part of Mary I’s coronation procession alongside Princess Elizabeth in 1553.

She slipped out of the limelight around 1554, after tensions arose surrounding the Wyatt rebellion. As her health started to decline, Mary I allowed her to stay at Chelsea Old Manor. It was here that she would later pass away on July 16th, 1557. This made her one of the few true survivors of the terrors of the reign of Henry VIII.