For centuries, the people of Judaea had seen many foreign dynasts claim hegemony over them; the Greeks were but the latest. Antiochus IV’s interactions with the Judaeans were, to put it mildly, troubled. Does Antiochus IV deserve the mantle of villainy that ancient sources such as the Bible place on him? He is portrayed as the personification of religious persecution and extreme cruelty. The confluence of the Greek and Judaic worlds leaves historians with a rare problem of having extant sources from both cultures. However, that does not always mean they align.

Babylonian Captivity and the Arrival of the Greeks in Judaea

The campaigns of Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon had led to the destruction of Jerusalem, the First Temple of Solomon, and the autonomy of the Kingdom of Judah in one fell swoop. Displaced from their homeland and the center of their worship, the inhabitants of Judah were taken back to Babylon, and Judaea, now called Yehud, became merely a province of a larger Babylonian state structure.

Unlike their time in Egypt, these people would not need another Moses to catalyze their return to Judah. According to Josephus, this role was played by the Persian king Cyrus. Fresh from his own victories over the Babylonians, he allowed the Judeans, having spent nearly five decades in Babylon, to return and “gave them lead to rebuild their temple.”

The Judeans, some of them having never been to the land they called Israel, established themselves amongst the new priestly class of the Second Temple, garnering animosity from those who had never left for Babylon. The internal strife amongst sects of the Judeans during this period would prefigure future conflicts that would be exacerbated by the emergence of a new power in the region.

The Achaemenids were toppled by Alexander the Great during his conquest of Persia. Alexander’s untimely death enabled one of his generals, Selucus, to claim a large region of what had been the Persian Empire. Seleucid rule was characterized by conflict with the other Successor Kingdoms, native populations, breakaway dynasties, and eventually Rome.

Their conflict with the latter led to a defeat in which the Seleucids were forced to sign the punishing Treaty of Apameia in 188 BCE that stipulated them to pay the Romans an indemnity of 12,000 talents of silver to be paid out in 12 annual installments. These circumstances would have profound effects on not only the Seleucids but also the taxpayers of Judaea.

The Issue of Terminology

As Antiochus IV rose to power, the Judaeans were dealing with issues of their own. It may seem pedantic but terminology does matter in terms of conceptualization and understanding, especially when looking at the ancient world. Today, the word Judaism is reductionist, reducing many regional and theological differences to a single word. The same was certainly true during the period of the Maccabean Revolt. As Steve Mason argues in his seminal work Jews, Judaeans, Judaizing, Judaism: Problems of Categorization in Ancient History that there was no one group of people who could be monolithically labeled as “Jews.”

Modern religious connotations of the word dilute the complexities and diversity of the various groups of people in the ancient Levant. It also seems to push them solely into the world of religion, another anachronistic term they would not understand, stripping away their simultaneous existence as a fully functioning political unit. Further to that point, there was far too much sectarianism within the society to be limited to a single all-encompassing term. Stretching into the Roman period, we know there were such distinct groups as the Pharisees, Essenes, and Sadducees, with varying roles and beliefs within Judaean society. This is not even to mention the various regional differences between Idumaeans, Galileans, and Samaritans.

There is no consensus among scholars on how the Jewish/Judaean people would have seen themselves in the context of others, such as the Seleucid Greeks, but for the purposes of this article, I will use the term Judaean to convey the importance of the geographical and religious ties of the people Antiochus IV came to rule.

The Rise of Antiochus IV Ephiphanes and the Syrian Wars

The young Antiochus was born into a world where his father, Antiochus III, was, according to Diodorus Siculus, considered the “king of Asia.” However, the defeat at Magnesia in 190 BCE and the Treaty of Apamea changed the balance of power. Due to its stipulation, reports Appian, the younger Antiochus was sent as a hostage to live amongst the Romans.

After the death of Antiochus III, the new king, Seleucus IV, recalled his brother to Syria. As Antiochus made his way back to Syria, he stopped off in Athens where he received the news that his brother had been killed as the result of a plot masterminded by a royal advisor named Heliodoros. The conspirator placed the slain king’s son, yet another Antiochus, on the throne.

Having spent over a decade in Rome, the politically savvy Antiochus spotted his opportunity and refused to yield the throne to his nephew. Garnering support from the Hellenistic dynasts Eumenes and Attalus of Pergamon, Antiochus forced himself onto the Seleucid throne, becoming Antiochus IV. His predecessor and nephew died a mysterious and obscure death, leading many to question Antiochus IV’s complicity and, in turn, the legitimacy of his ascension.

Moving eyes away from the internal strife and controversy, a dispute was raised by Ptolemy VI Philometer, who claimed control of the region of Coele-Syria. Much as his father had, Antiochus VI, in a typical decisive fashion, launched an invasion, the speed of his response surprising the Egyptians. In the course of his campaigns in Egypt, Antiochus reduced the rival dynast’s kingdom to little more than the city of Alexandria itself. Nearly victorious, it was only the intervention of the Romans, with whom he had strove to retain good relations, that stopped him.

The Office of the High Priest in Jerusalem

In 175 BCE, a dispute had broken out between the Seleucid local authorities and the High Priest Onias III. Newly crowned, Antiochus IV could not afford dissent or a disruption in the stream of tax revenue. Jason, the brother of Onias, made overtures to Antiochus involving a substantial bribe if he were given the position. The bribe came in the form of a bid, or tax harvesting contract, through which he would raise the funds to pay Antiochus by raising a specified amount of revenue in the form of taxation on his prospective subjects.

It should be remembered that Antiochus III granted the Judaeans special fiscal dispensations after his conquest of the area in the Fifth Syrian War. This act was meant as a way to build loyalty with a people that occupied a strategic area of land between the Seleucids and the Ptolemaic dynasty in Egypt.

Jason also promised that additional taxes would be levied if Antiochus were to accept the construction of a gymnasium in the city, effectively reorganizing the city as a full-fledged Greek polis. Dr. Franz Mittag suggests that this served the purpose of both increasing tax revenue and counterbalancing against the older, traditionalist elite represented by Onias III.

According to 1 Maccabees, Jason’s program of Hellenization took hold, and “they sacrificed to idols and profaned the Sabbath.” Altars were built and animals were sacrificed upon them in a manner that did not adhere to the Judaean practice, including the sacrifice of “pigs and other unclean animals.”

As abhorrent as the acts are portrayed in Maccabees, there is nothing to suggest that there was widespread dissension amongst the wider populace. Jason’s problems did not come from an unruly populace but from his inability to hold up his end of the financial deal struck with Antiochus.

The Temple Treated as a Treasury

Three years after his initial ascendancy in 172 BCE, Jason was deposed by yet another claimant to the office. A man named Menelaus, 2 Maccabees tells us, bribed Antiochus for the post of High Priest. Eager to receive the money promised to him, Antiochus had Jason deposed.

There is no evidence to suggest that Menelaus was any less influenced by Hellenization than his predecessor. In fact, 2 Maccabees reports that his brother Lysimachus regularly desecrated the Temple by entering it and removing objects from the treasury.

Word spread of Lysimahcus’ sacrilegious actions and a mob formed. To make matters worse, it was believed that the new High Priest was complicit in his brother’s transgressions. Lysimachus called up 3,000 men to put down what had quickly become a riot. Stones, bits of wood, and even ashes were flung at the soldiers as they approached. Some were wounded, others were killed. Soon the soldiers broke and fled in panic. Lysimachus himself was not spared from their wrath; he was killed near the steps to the same treasury which he defiled with his presence.

Receiving reports of unrest, Antiochus stopped in the city on his way from Tyre. A delegation of three men had brought charges against Menelaus and sought the King to arbitrate. Proven to be reliable and effective, Menelaus offered the King another bribe to be found innocent. Rather than answering for his transgressions, he was found innocent and the Judaeans who had brought such charges against him were executed.

Much like the earlier episode with Lysimachus, Antiochus, at this time, entered the Temple to extract 18,000 talents of silver – presumably as a form of payment for back taxes owed to him. For a Greek, seizing funds from a temple was not unprecedented; for a Judaean this was inconceivable.

The Case Against Antiochus: The Siege of Jerusalem and the Issue of the Decree

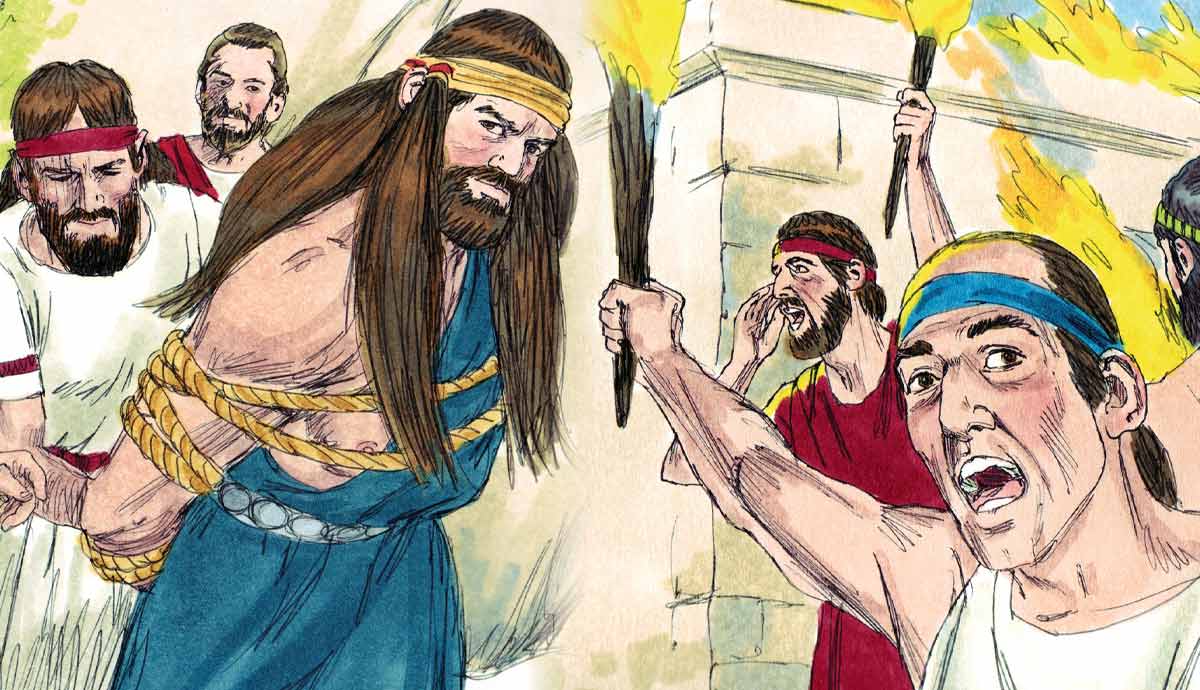

Having extracted the necessary funds, Antiochus set off on another campaign in Egypt where it was rumored that he had fallen in battle. Seizing the opportunity, the deposed Jason returned to Jerusalem. Menelaus sought refuge in the Temple while the populace was subjected to the rapaciousness of Jason’s men, who began slaughtering them “without mercy” or regard for kinship.

Hearing of the unrest, the local Seleucid commander, who resided in Samaria, moved quickly to quell the revolt. The city was retaken and a new stronghold was built next to the Temple called the Akra. Both Josephus and the author of 2 Maccabees tell us that Antiochus IV was there himself, giving the order to sack and plunder the city, which resulted in the deaths of “80,000 people.” The walls were torn down, the city was plundered, and many of the able-bodied inhabitants were enslaved.

Sources such as the Book of Daniel, 1 and 2 Maccabees, and Josephus report that in 167 BCE an edict was issued by Antiochus IV which suspended the worship or practice of native beliefs. They tell us that Jewish holy law was suspended, circumcision was prohibited, daily sacrifices were banned in favor of impure ones, violations of the Sabbath, the construction of foreign altars, and the worship of foreign deities such as Zeus was conducted.

The two most egregious reports of religious suppression come from 2 Maccabees and tell the story of Eleazar the Mother and Seven Sons. In both stories, the Judaeans are threatened with death to eat unclean food. Their piety and refusal to eat the food eventually results in their torture and death. In the latter episode, Antiochus is personally on hand and the cruelty shown to the local populace is spurred by his ire.

Antiochus in Jerusalem: Fact vs. Fiction

The siege of Jerusalem and the reported slaughter of the populace can, in all probability, be taken as factual. Purging a local populace through death and enslavement was not uncommon amongst victorious Hellenistic generals. Judaean sources report the deposed High Priest Jason doing the very same thing. It is entirely possible that Antiochus took the discord caused by Jason re-entering Jerusalem as a more general revolt and moved to put it down quickly.

However, the stories of him forcing Judaeans to eat pork in front of him upon the threat of death are reported nowhere else and almost certainly embellished. There would be no incentive for him to single out the Judaeans amongst the many other religious groups in the empire for persecution. This would only sow the seeds of civil unrest; something Antiochus could ill afford with the Syrian Wars raging. His fear of even minor rebellions is demonstrated by his swift and heavy-handed reaction to Jason’s re-entry into Jerusalem.

The next issue surrounds the existence of the edict that is cited in Josephus and Maccabees. What is troubling about these sources is that they are often inconsistent on the exact circumstances of their stipulations. Taken in tandem with the fact that there are no other sources that cite this “decree,” it is dubious that such an edict was issued in this manner, especially on an empire-wide scale as 2 Maccabees claims.

The introduction of foreign cults would not have been a strange consequence for a victorious Greek king, especially in the neighborhood of Akra where Greek troops were now permanently stationed. We know that other elements of Greek culture had already been introduced to the city (and even adopted by some of the populace), so their presence there does not inherently prove the suppression of native beliefs.

Antiochus IV and Seleucid Rule in Judaea: Conclusion

The exact event that sparked the beginning of the Maccabean Revolt is not clear. Was it the economic burden (increased levels of taxation), civil strife between the two factions of presumptive High Priests, or Antiochus’ excessive cruelty?

The issues the Judaeans experienced in the years leading up to the Maccabean Revolt were certainly not helped by the internal sectarianism present amongst the populace, most notably in the form of the dispute over the office of the High Priest between Jason and Menelaus. The consequences of their respective ambitions were exacerbated by the interference of a cultural outsider who did not fully understand the intricacies of Judaea himself, nor did he have the time to focus solely on it. Wars with Ptolemaic Egypt, dissension in Bactria, and the other administrative duties of running a huge, multi-ethnic empire would have consumed his days.

The strategy of controlling local authority by displacing older elites was not new. In Ptolemaic Egypt, priestly families were often replaced and, as Dr. Honigman points out, Antiochus IV had already supplanted ruling elites in Uruk. “The Seleucids’ attempt to control the appointment of the Jerusalem High Priests was indeed an innovation introduced by Antiochus IV, who exploited his appointees’ weakness—their lack of dynastic legitimacy—to extort sharp tax rises from them.”

There was a fundamental difference in philosophy that the “gentiles” never quite squared. To the Judaeans, the state’s political apparatus was the means to perpetuate their faith. Many in the Greco-Roman world would have held the inverse to be true. While the Julio-Claudians styled themselves as the descendants of Venus, deifying their own deceased family members, the people of Judaea could never truly accept any head of state that put themselves in between the mortal and divine realms in such a manner. It was a divergence in perspective at the most basic philosophical levels.