Natural catastrophes often prove epochal, providing a structure to our collective sense of history and identity. It is telling that in the mid-fourth century, Ammianus Marcellinus was all too aware of the devastation wrought by the Antonine Plague in the second half of the second century: it “polluted everything with contagion and death, from the Persian frontiers to the Rhine and Gaul”.

This pestilence that wracked the Roman Empire was one of antiquity’s worst pandemics and it had a profound impact on the course of Roman history.

A Golden Age? The Roman Empire on the Eve of the Antonine Plague

On the eve of the Antonine Plague, few would have foreseen that the Roman Empire was about to face a reckoning. Stretching from the frontiers in northern Britain through to the Arabian Peninsula, the empire was at its apogee. Although not as expansive as it had been following Trajan’s conquests, it was in a period of sustained stability. The transfer of power from one emperor to another — for so long a competition fraught with intrigue and outright conflict — had been passed, rather benignly, from one nominated successor to the next. Even the accusations of interference that swirled around Hadrian’s succession did little to disrupt the prevailing political calm.

It was in this environment that Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus emerged. Childless, the emperor Antoninus Pius had adopted his nephews, Marcus Aurelius and Lucius Verus, to succeed him. When Antoninus Pius died in 161 CE, imperial power duly passed to Marcus and Lucius, with the former very much the senior, more experienced partner. There were signs from the start, however, that all was not right in the Roman world. Rome was wracked by a deadly flood in 161-2 CE, as the Tiber burst its banks, causing significant death and destruction in the city.

Further afield, trouble was also brewing on the empire’s eastern frontiers.

The Antonine Plague and the Roman-Parthian War

Shortly after the death of Antoninus Pius, the Parthian Empire made a move against Rome. Vologases IV, the king of Rome’s imperial rivals in the east, marched into Armenia in late 161 CE and expelled the Roman client king. The attempt at immediate Roman retribution was a disaster. The governor, Marcus Sedatius Severianus, led his army into a trap in which it was massacred (though not before the governor had killed himself). Lucius Verus was dispatched eastward at the head of an army to restore Rome’s authority. In 163 CE, the Roman forces drove deep into Armenian territory, recapturing the capital, Artaxata, for which Verus was emblazoned with the title Armeniacus (‘conqueror of Armenia’).

At the same time, however, the Parthians countered. This time they launched a campaign against Osroene, one of Rome’s client kingdoms in Mesopotamia. Two Roman armies were duly dispatched to restore Roman control. By 165 CE, the first army had re-taken the Osroene capital of Edessa and re-instated the former king. The second army, led by the future rebel Avidius Cassius, advanced down the Euphrates River into Parthian territory, eventually sacking the city of Ctesiphon and compelling the citizens of Seleucia to open their gates to the invaders.

Any Roman exultation at their successes was short-lived. Despite their victories, Cassius’ army was deep inside enemy territory and the depredations of war and beginning to feel the strain. Worse was to follow. Soon, the Roman forces were wracked by an unknown and devastating pestilence. Whatever this sickness was, it stuck to the Roman forces and traveled back up the Euphrates with them, infecting more and more people. In the years that followed, the sickness was likely responsible for the sudden death of an emperor. Traveling back to the Danubian frontier where Marcus had been campaigning, Lucius Verus suddenly fell ill and died. Although some sources attribute his death to an attack of ‘apoplexy’, the emperor was quite possibly a victim of the devastating sickness that his soldiers had carried back to the empire with them from the scene of his greatest triumph.

What Was the Antonine Plague?

When looking through the annals of Roman history, pestilence and plague are most commonly attributed to the anger of the gods. According to Livy, as early as 399 BCE, the Romans had introduced a ceremony (the lectisternium) to appease the gods, with the fledgling city the victim of an oppressive pestilence. The Antonine Plague was also attributed to divine retribution. The Historia Augusta (always to be used with caution…) claims that the illness was a punishment for Cassius’ sack of Seleucia, which had willingly opened its gates to the Romans. Notably, this was also the story echoed by Ammianus Marcellinus some centuries later, indicating the longevity of the tradition of divine wrath.

The origins of the plague remain as much a mystery as the question of what the disease actually was. Of course, ancient epidemiology is a difficult task, with the absence of available evidence making the identification of millennia-old pathogens a particular challenge. The prevailing theory among historians, however, is that the Antonine plague was an outbreak of smallpox. Because this disease offers some immunity to survivors, this may explain why, after the initial peak of the Plague during Marcus’ reign, there was a brief interlude before the re-emergence of the pestilence during Commodus’ reign several years later. The mortality of the disease, whether smallpox or another contagion, had a profound impact across the empire. Diverse sources, brought together, allow historians to understand these impacts. In Egypt, in particular, the valuable testimony of papyrological evidence presents a bleak view of life during the Antonine Plague, including reductions in leases of farmland and reduced numbers of taxpayers. An overall reduction in evidence of typical imperial administration — the bureaucracy of power — also indicates a significant disruption (and probable population reduction), during this time.

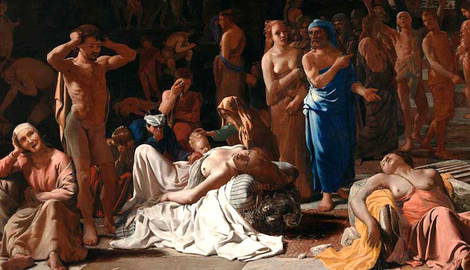

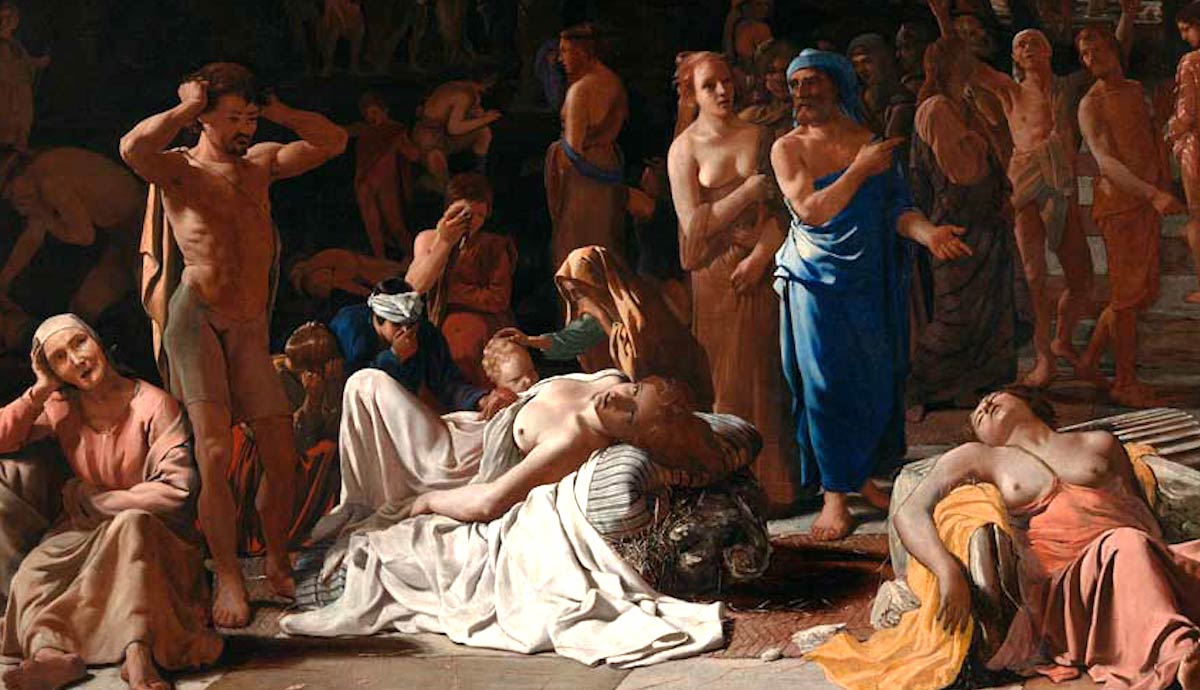

Rome’s Most Famous Doctor: Galen and the Antonine Plague

For other plagues in the ancient world, historians are lucky to have access to substantial narratives of the devastation wrought by these diseases. Centuries before the Antonine Plague, for instance, the Greek historian Thucydides presented a graphic account of the carnage that engulfed Athens during a plague, likewise during that city’s golden age. Unfortunately, no such narrative exists for the Antonine Plague (in fact, there is a striking absence of contemporary historiography for this period full stop). However, one of the most valuable sources for the plague, its symptoms and its effects, fortunately, comes from one of the ancient world’s most celebrated physicians: Galen. In fact, such is the association of the doctor with this pandemic, that it is sometimes referred to as the Plague of Galen (the doctor has usurped the emperors!)

Born in around 129 CE in Pergamon, Asia Minor, Galen arrived in Rome in 162 and quickly gained prominence among society. He eventually became the emperors’ physician, serving not only Marcus and Lucius, but also Commodus, and later Septimius Severus and Caracalla, indicating that Galen was evidently held in such high regard so as to avoid the internecine civil war of the early 190s CE.

As an observer of the plague, Galen is, unfortunately, scattered and rather brief. However, it is through his writings that the clearest impression of the disease and its symptoms come to light. These included fever, vomiting, ulcers, and catarrh, giving some indication as to the way the population of the empire suffered during the plague years. The plague also afflicted Galen’s household, causing the death of a number of his slaves. Certain snippets of Galen’s writing also support the identification of the disease as smallpox. The ancient doctor noted when he was traveling with the imperial household at Aquileia in 168-9 CE that the impact of the plague coupled with the harsh winter months was doubly deadly; harsh winters are known to be especially beneficial to the spread of smallpox thanks to more modern outbreaks of the pestilence.

Rome, China, and the Antonine Plague

Although travel was slower and more arduous, the ancient world was very much a connected world. Civilizations were connected by trade routes, one of the most important of which were the Silk Roads, linking Europe with Asia. Unfortunately, these routes also provided the means for diseases to travel, too. Describing the devastation wrought by the Plague of Athens, Thucydides described how it was commonly held that the sickness had arrived in the polis from overseas: “first of all from Ethiopia… and from there if fell on Egypt and Libya”, before arriving in the Piraeus, the Athenian port, and then ravaging the city itself.

There is a similar possibility that the plague that struck Rome during the Antonine period also originated in distant lands, further even than the lands of the Parthian Empire. During the middle of the second century, the Han Dynasty in China was also afflicted by a virulent plague. The ancient Chinese doctor, Ge Hong, described the symptoms of the sickness afflicting his homeland, and it has been argued by historians that Han China — like the Roman Empire — was being ravaged by smallpox. The Silk Roads would have connected China to the Parthian Empire, as well as Rome, meaning that the sickness may have originated in Central Asia before afflicting the two empires. Further supporting this hypothesis is the fact that, in around 166 CE, a delegation of people claiming to have been sent from Rome, arrived at the court of Emperor Huan. Archaeological evidence has indicated the connections between the two civilizations, particularly in terms of trade.

The Antonine Plague and the End of Rome’s Golden Age

The Roman Empire would be devastated by plagues again in the future, including the Plague of Cyprian in the mid-third century and the Plague of Justinian in the sixth century. The ravages of the Antonine Plague left deep scars on the imperial psyche, however, as we saw with Ammianus’ recollection of the pestilence. Worse still, the death of the emperor Lucius Verus was not the end of the empire’s suffering under the sway of the Antonine plague. Although the pandemic waned in severity for several years, it returned with a vengeance in the 180s, reaching a devastating crescendo in around 189 CE. The return of the pestilence to Rome is dramatically described by Cassius Dio, the senatorial historian. An eye-witness to the reigns of emperors from Marcus Aurelius to Severus Alexander, Dio was in Rome when the imperial capital was again struck by the pestilence. He describes an outbreak of a disease more deadly than any of which he knew, with two thousand people dying in a single day in Rome!

Worse than the disease, however, according to Dio at least, was the empire’s fate in having to endure the depraved reign of Commodus. The son of Marcus Aurelius had taken control of the empire in 180 CE and slowly sunk into megalomania, including masquerading as a gladiator in the arena and likening himself to Hercules! Cassius Dio’s history had pithily remarked that with the transition from Marcus’ reign to that of his son, the empire itself had passed from an age of gold to one of iron and rust.

Commodus could not be blamed for the ravages of the pestilence, but it was the Antonine Plague that had terrorized his father’s reign and certainly took the luster of Roman power in the later decades of the second century, helping to bring the curtain down on Rome’s Golden Age.