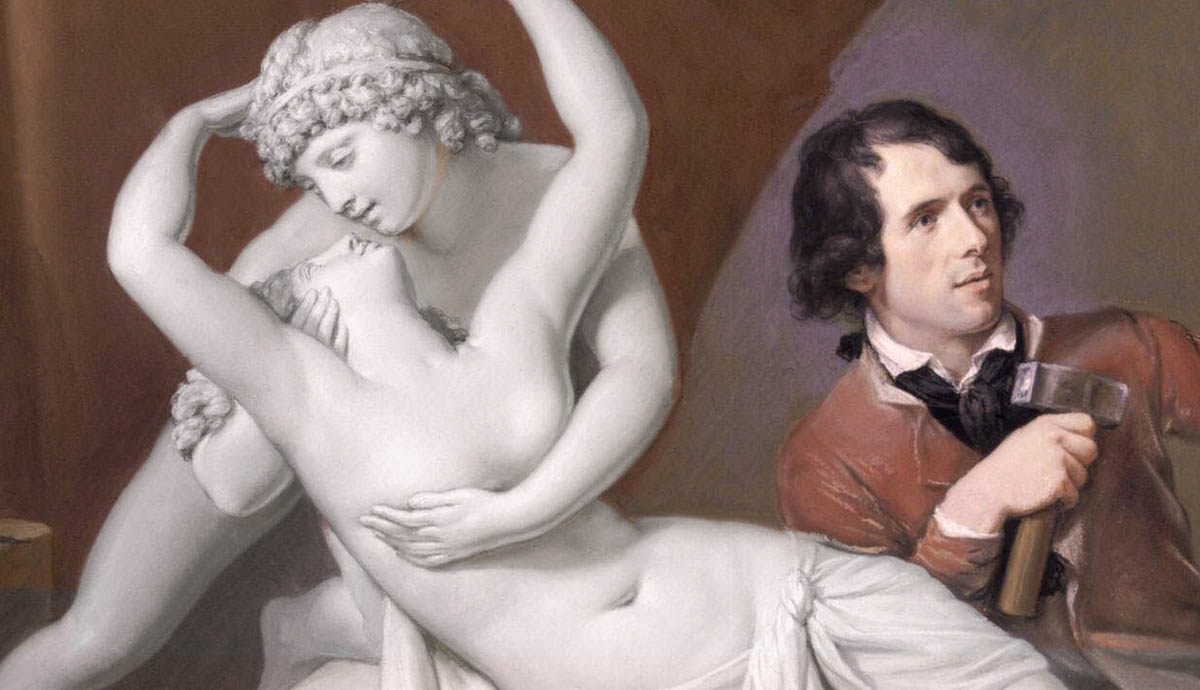

Antonio Canova was the first modern artist to have work in the Vatican Collections. He held the favor of both Napoleon Bonaparte and Pope Pius VII, served as a diplomat on behalf of the Papal States and saved the ancient art of his native Italy. Antonio Canova was a successful artist by any standard – beloved by the picky European public, showered with praise by the elites, and revered by his peers. When nascent Italian nationalism began to rear its head, it was Canova who created the Neo-Classical aesthetics that would later inspire Italian Revolutionaries fighting against Greater Powers. A Venetian to the core, Canova never truly understood the political idea of Italian unity. However, his impact on Italian state-building often remains underestimated. After all, Canova was not a politician nor a revolutionary philosopher; yet his story is about an artist creating a nation.

Antonio Canova and Art That Creates States

National affiliations are never fixed or predetermined. They do, however, always rely on a cultural or linguistic kinship that can shift depending on the period’s changing political trends. Thus, as an Italian in the 18th century, the idea of a unified nation-state with one dominant language and culture was still fresh and did not yet coincide with the Romantic notions of 19th-century Italy. The Romantic Revolutionaries of that era died with flags on the barricades, composed odes, and painted pictures to honor their Motherland.

Mere decades earlier, the exalted patriotism of the Romantic generation was non-existent. In Italy’s fractured history, it is almost impossible to draw a precise line between the birth of nationalism and the sentiments of unity that predated it. Yet, if the politics of Greater Powers framed nationalisms, then it was art that inspired and propagated it. Antonio Canova’s masterpieces serve as a prime example of art that promoted unifying ideals that later instigated waves of Italian nationalism. In this way, Canova was seen as one of the heroes of the nationalist movement even when the artist himself was long gone.

Antonio Canova was an Italian in a time of turmoil: cultural liaisons, political formations, and personal affiliations were all at odds. Born in the Republic of Venice, Canova saw his country become a Habsburg Province, then a Napoleonic kingdom and died in the Kingdom of Lombardy-Venetia. Canova was, in his essence, an “Italianata” – both a Venetian and an Italian, someone opposed to the undisputed French domination of Europe and simultaneously not an activist of the Italian unification.

In his book about Canova, Christopher John writes the following:

“Cultural nationalism unlike its political counterpart, was essentially not militant but sentimental, and needed only peace and political stability for the highest possible level of cultural production. The thought of a political movement to unify Italy, with its attendant civil wars, destruction, economic ruin, and threat to art and monuments, would have been utterly abhorrent to an individual of Canova’s sensibilities.”

While an artist could indeed be fascinated by the legacy of his native land, he did not necessarily support any political agenda related to that native land. Yet, in the case of Antonio Canova, Italian nationalism did indeed find its roots in his art because of two principal factors: Canova’s mind-blowing fame and the universal appeal of Neo-Classicism.

Neo-Classicism and Italian Nationalism

As a tapestry of conflicting legacies, the Venetian Republic was in a state of declining power when Canova was born in 1757. A stonecutter’s son, Canova began his life like so many Renaissance geniuses did before him: he was discovered at an early age by a worthy mentor, then taken in by powerful patrons. Despite all the similarities between the biographies of the sculptor and his illustrious predecessors, one detail sets Canova apart. While the Renaissance masters wanted to imitate and ultimately outshine Antiquity, the generation of Neo-Classicists was not just admiring and improving the past but partially appropriating it, claiming it as their own. This is how the first seeds of nationalism sprang from cultural admiration.

Canova’s life changed forever once he saw the casts of ancient works in the collection of Filippo Farsetti, for whom he also completed his first independent work, Two Baskets of Fruit. Ever since the early years of his apprenticeship, Canova pursued one passion – the Classical art of Ancient Rome.

As a young man, he set out on a Grand Tour around Italy before settling in the Eternal City in 1781. It was then that his first truly Neo-Classical work appears – Theseus and the Minotaur. Invaded by treasure hunters, archaeologists, artists, and onlookers, Rome was a place where one could not help but fall in love with the legacy of an Empire long gone. In an Italy that lacked stability, the pure and simple lines of marble sculpture and architecture spoke of an ideal beauty and a past that was more imagined than real.

The shared idea of a once-great legacy unified Italians and made Canova seek the language of Neo-Classicism. Venice differed politically from Rome or Naples; all they had in common was a cultural interest in the Romans as well as their legacy strewed across the peninsula. It was from that legacy that Neo-Classicism sprang, inspiring state-builders. If art and its perception were shared, a common language could be established. With a common language came a common political vocabulary and an idea of a shared government. But Canova thought about art, not nations. He simply had started promoting a style that was considered undeniably Italian, despite its popularity in Europe and beyond.

The Protector of The Past

Antonio Canova quickly rose to fame in Rome. Charming and well-liked, Canova completed commissions for the most prominent individuals of his time. In fact, his collaboration with the Popes Clement XIII and Clement XIV helped spread Neo-Classicism.

However, Canova’s obsession with Antiquity did not stop there. Soon enough, Canova became a protector of monuments. The French invasions of Italy and the establishment of the Napoleonic Empire did not intimidate the artist. Gathering support from his wealthy patrons, the sculptor led successful campaigns to protect the masterpieces he admired. He lay his pride aside to beg Napoleon to safeguard Italy’s ancient treasures. For Canova, art was as precious as human life. Ironically, such would be the attitudes of nationalists towards their past and shared culture of their respective states. Canova lay the framework for future nationalists while sculpting mythological deities and heroes, whose life-like faces reflected the Classical myths of pure harmony and calm beauty.

Canova was an artist whose patrons included the most famous men and women of his time. He was indeed renowned and very much sought-after. Canova’s choices dictated artistic tastes and determined regional sensitivities. He viewed himself and his fellow artists as the continuation of the Roman legacy that he cherished and promoted. Thus, he used Neo-Classicism as a language of power to convey a message about the significance of shared culture.

Neo-Classicism and Propaganda

When Antonio Canova depicted Napoleon as Mars the Peacemaker, it was not simply by chance. This sculpture is an allegorical portrayal of a 19th-century man within the context of Antiquity. A brilliant military leader appeared as a god of war, yet, ironically, he also intended to bring peace. As an outstanding diplomat, Canova surely realized that the Neo-Classical shell of his pieces could carry significant political weight.

Canova used the same approach when executing his statue of George Washington requested by Thomas Jefferson. Presenting the first US president as the Cincinnatus of his time, a hero of the Republic, was an effective way to use Neo-Classicism to deliver another political message. Canova’s works herald the start of folk hero worship that would eventually become the mark of nationalism. With its regularized forms, Neo-Classicism turned out to be a suitable style for presenting folk heroes by likening them to Greek and Roman deities.

Canova did not bide his time while the French confiscated major artworks from the Vatican Collection. He once again used art to deliver a message about Italian legacies and power, but this time he used Neo-Classicism in a different manner. He wished to visualize la gloria d’Italia at a time when the peninsula faced despair and destitution, which he did in the form of a Pantheon commemorating the greatest geniuses of Italy.

Antonio Canova’s Pantheon

Canova’s Pantheon (Tempio Canoviano), much like the famous Walhalla Temple near Regensburg, marked the debut of nationalism in Europe. If previous monuments celebrated the achievements of certain outstanding individuals, the Tempio Canoviano was a testament to brilliant people all hailing from the same nation. In the end, without Antonio Canova and Ludwig of Bavaria, modern-day national commemoration in Europe could have acquired a very different style.

In 1808, Canova asked students in his workshop to sculpt herms of illustrious Italians for the Pantheon in Rome. In 1820, Canova’s collection was transferred to the Capitoline Museums. Canova’s Pantheon focused on great artists and scientists, combining the Renaissance adoration of genius and the modern Neo-Classical aesthetics. The Pantheon exuded power and unity. However, that power and unity did not come from military victories or politics like in the case of Napoleon and Washington. Canova argued that Italy could be nurtured by brilliant artists as well as politicians. Unhappy with the French occupation, Canova forged a dream of Italian identity through art – through his own works and the works commissioned from others.

When in 1816 Canova managed to return some of the art Napoleon had whisked away back to Italy, he once again installed himself as a figure for the rising Italian nationalism movement to behold. Between producing and protecting art, Canova’s life was filled with travels and research. His health, however, soon gave way, and, in 1822, he died. In sum, Antonio Canova aided Italian nationalism in ways he, himself perhaps never fully understood.

A Life After Death: The Promotion of Antonio Canova

Antonio Canova’s Neo-Classical works were perfect manifestations of Italian nationalism. Copies multiplied, and vendors opened their doors to welcome the influx of tourists that craved to see his eye-pleasing pieces. Canova became a household name already during his lifetime, but after his death, his sculptures’ perfect proportions and sheer brilliance could leave very few people indifferent. Before rebellious Romanticism became the leading style of European nationalism, Neo-Classicism set the stage. Canova’s Cupid and Psyche, Perseus with the Head of Medusa, or Theseus and Centaur all promoted myths which came from Antiquity’s vast legacy that Canova claimed for his fellow Italians.

In the mid-1870s, the famous playwright Lodovico Muratori started creating plays about great Italians, shaping the folk heroes for a new nation. As he was the subject of numerous posthumous biographies and at one time arguably the most famous artist in Europe, Antonio Canova could not avoid becoming the hero of Italian nationalism. After all, he did save Italy’s legacy from invading forces, created a Pantheon of national heroes, established and promoted a new artistic language that was Roman in nature, demonstrated how one could use past legacies and connect them to present-day sensitivities, and, above all else, was incredibly famous and successful.

Antonio Canova made for a brilliant brand, both professionally and in his personal life, that attracted young people on their Grand Tours to Italy, igniting their imaginations. Muratori’s play tells a story of Canova’s romantic love for his maidservant, something which really could have happened or could have simply been a beautiful legend. Regardless of the truth, it can hardly be denied that one of Canova’s truest loves was always the heritage and art of his native Italy.

Canova was far from an Italian nationalist in our modern sense. But without him, early Italian nationalism would have been a very different movement with a very different set of heroes. In a way, Canova’s story is one of art that creates nations, and artists who outgrow their limitations, for better or worse.