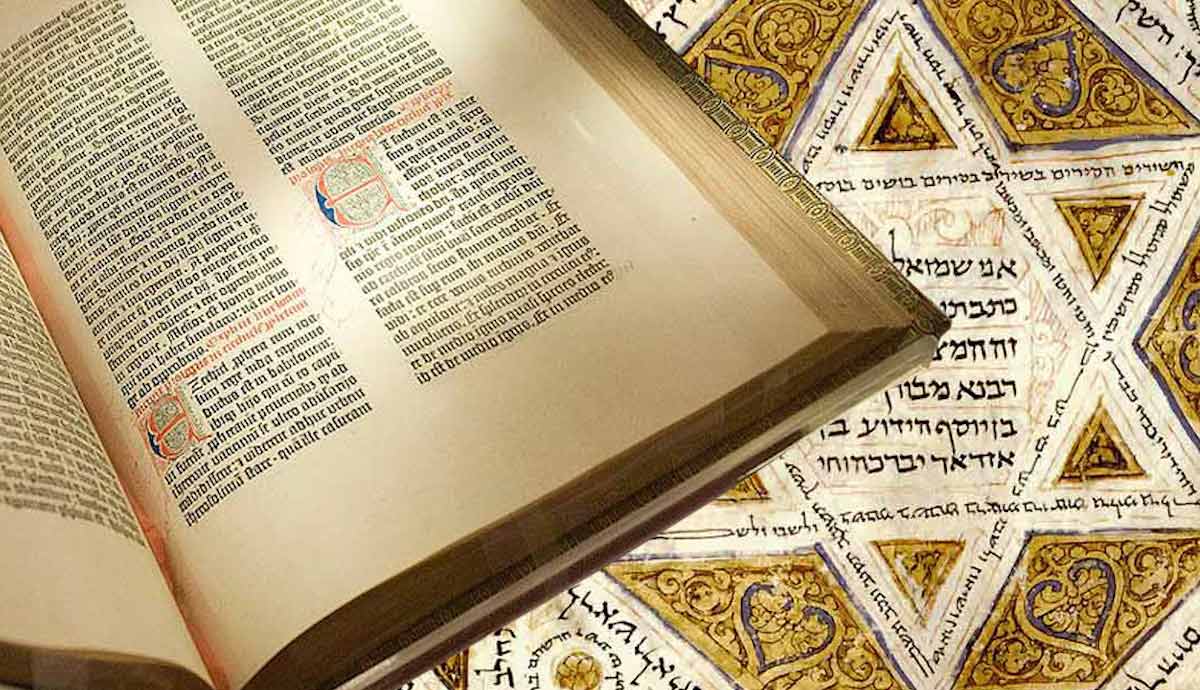

Many skeptics believe that some books have been purposefully omitted from Protestant Bibles. They claim these omissions lead to manipulation of teaching in mainstream churches and were nefariously done to hide knowledge. As proof, they point to the lack of apocryphal books in Protestant Bibles after the 1800s. To them, the omission of the Apocrypha served a nefarious purpose. So, were books nefariously omitted from the Bible?

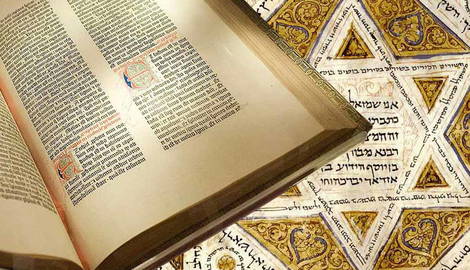

Apocrypha and Bibles

The term Bible means book. The Bible refers to the compilation of works that the Holy Spirit inspired the authors to write. They are useful for teaching and suitable for the development of doctrine. The Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Protestant Bibles do not have the same books. The Protestant Bible has 66 books. The Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Bibles have 73 and 81 books respectively. The difference comes in with the Deuterocanonical books. Is this evidence of manipulation? Or are there less nefarious reasons for these differences?

Why Differences in the Number of Old Testament Books Exist

It all started with the Septuagint. The Septuagint is the Greek translation of notable literary works of the Jews. Ptolemy II Philadelphus wanted to preserve significant works from various cultures. He wanted a Greek copy of the Hebrew Bible for his library in Alexandria. He thus requested that Jewish scholars translate some works of significance to them. Supposedly, 72 scholars traveled from Jerusalem to Alexandria to work on the translations. They translated the Hebrew Bible and several other books common to Jewish culture. We know the compilation of these translated books as the Septuagint. Scholars also refer to it as the LXX in reference to the 70-odd translators who worked on it.

The Septuagint became popular among Jews during the diaspora. They were more familiar with Greek and could often no longer speak or read Hebrew. The Septuagint also became more popular in Palestine. Aramaic and Greek became the common language there, rather than Hebrew. The New Testament quotes from the Greek Septuagint, not the Hebrew Old Testament. Early Christians also often preferred the Septuagint over the Hebrew Old Testament. They were more familiar with Greek than with Hebrew.

The Septuagint contained books the Jews considered as part of the Hebrew Bible canon. The word canon means reed or measuring stick and implies that books that are part of a canon set an authoritative standard for believers. The Septuagint also contained non-canonical books referred to as apocrypha. The term apocrypha comes from the medieval Latin word apocryphus which means secret. In turn, apocryphus comes from two Greek words apo (away) and kryptein (to conceal or hide).

The meaning of the word apocrypha changed over time. Originally, it referred to texts meant for private reading. Christians only read from canonical works at gatherings. Later, during the Reformation, apocrypha came to mean esoteric, heretical, or even false. The change was due to the attitude of Reformers toward apocryphal books.

Use of the Septuagint in the early Church was common but the Septuagint also contained books not included in the Hebrew Bible canon. Different Christian communities considered some of these apocryphal books as authoritative. Yet, there was no consensus on the issue in broader Christianity. The Council of Carthage, held in 397 CE, decided to accept some of these books as authoritative. This meant that the Church recognized a second canon. Books that were considered apocryphal before, now became known as Deuterocanonical books. The change means these books now had authority and clergy could use them in the liturgy. It also meant they could use them for teaching and to establish doctrine.

Different views on the canon emerged before the Great Schism. By the time of the Great Schism in 1054 CE, two primary views on the Bible canon were dominant. The Eastern tradition considered all the books in the Septuagint as canonical. The Western church accepted only some of the apocryphal Septuagint as Deuterocanonical.

The Deuterocanonical books of Eastern Orthodoxy are also called the Anagignoskomena. They contain books not included in the Roman Catholic canon. They are books, or portions of books, such as 3 Maccabees, 1 Esdras, and Psalm 151.

Protestants rejected the canonicity of all Septuagint books outside of the Masoretic canon. They regarded these books as apocryphal. Yet, they included them under the apocryphal section of their Bibles. The apocrypha do not carry the same authority as canonical books in Protestantism. This is because these books are not considered “inspired.” Thus, they are not used for teaching or to establish doctrine.

The Council of Trent lasted from 1545 to 1563. During the council, the Roman Catholic Church evaluated the New Testament canon again. They reconsidered it in response to the Protestant Reformation’s stance. During the 1546 session, the council reaffirmed the canonicity of their Deuterocanonical books. They asserted that these books had equal status with the other books of the Old Testament.

So, the Eastern Orthodox Church accepts all the books of the Septuagint as canonical. The Roman Catholic Church excluded some of the books of the Septuagint in their canon. Protestants, in turn, accept only the books of the Hebrew Masoretic Text for their canon.

The Compilation of the New Testament Canon

Early Christians wrote many gospels and epistles. Some of these contained information that was not reliable or truthful. Others even contained false teachings. The Church Fathers had to determine which books should be part of the New Testament canon. To become part of the canon of the New Testament canon, a book had to meet certain criteria.

The first had to do with apostolic authority. Only works by an apostle or a close associate of an apostle would suffice. The author did not have to be an eyewitness but had to have a close connection with someone who was. Luke is a good example (See Luke 1:1-4).

A second factor was orthodoxy of doctrine and theological consistency. Books that did not align with accepted theology could not become part of the New Testament canon. As an example, the Book of Enoch (1 Enoch) was well known to the Church Fathers. It contained views that were incompatible with accepted teachings. As such, the Church Fathers could not accept it as canonical.

A third criterion was community acceptance and liturgical use. Works that were not used by the greater Christian community could not qualify as Bible canon. When a book was widely used in liturgical practice and worship, it was more likely to become part of the canon.

The oldest known list of the 66 books of the New Testament appears in Athanasius of Alexandria’s Paschal Letter of 367 CE. It took more than 250 years to establish the canon of the New Testament.

The Eastern Orthodox, Roman Catholic, and Protestant churches have the same New Testament. They consider the same 27 New Testament books canonical. Scholars have discovered more than 30 different gospels. Only four appear in the Bible. Those excluded did not meet all the set criteria.

A vast minority of churches have more than 27 books in their New Testament canon. The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church, for example, has a larger New Testament canon. They added the Sirate Tsion, Tizaz (The Book of Herald), Gitsew, Abtilis, and the Book of Clement among others. They have 35 books in their New Testament canon.

Inclusion in Print vs Inclusion in the Canon

Protestant Bibles included the apocryphal books of the Septuagint until the 19th Century. The British and Foreign Bible Society were very influential in the 1800s. They removed the apocryphal section from the Protestant Bible. They did so to save on the cost of printing Bibles. It led to most British and American Bibles excluding the Apocrypha from then on. They published only the 66 canonical books of the Protestant Bible. In Europe, the 14 apocryphal books often remained in editions of the Bible. It resulted in a Bible of 80 books in three sections: Old Testament, New Testament, and Apocrypha.

Conclusion

With this background in mind, we can consider the claim made in the beginning of this article. To Christians, the Bible is a book containing the canon of Scripture. To Eastern Orthodox believers, their whole Bible is canonical. To Roman Catholics, their Bible is canonical, but some of the Eastern Orthodox Bible books are not. To Protestants, many Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic Bible books are apocryphal.

It is true that some books are no longer included in the Protestant Bible. The omitted books are apocryphal. They were never part of the Protestant canon, nor of the Hebrew Bible canon. Their omission does not impact the authority or sufficiency of the Protestant Bible. There was no malicious or nefarious intent in omitting the apocryphal books. They do not contribute to the establishment of Protestant doctrine or teaching. The inclusion of the apocrypha in the Protestant Bible in the past was due to the use of the Septuagint in the early church. It was the result of tradition rather than the legitimacy of these books. The claim of nefarious intent in omitting these books is thus false.