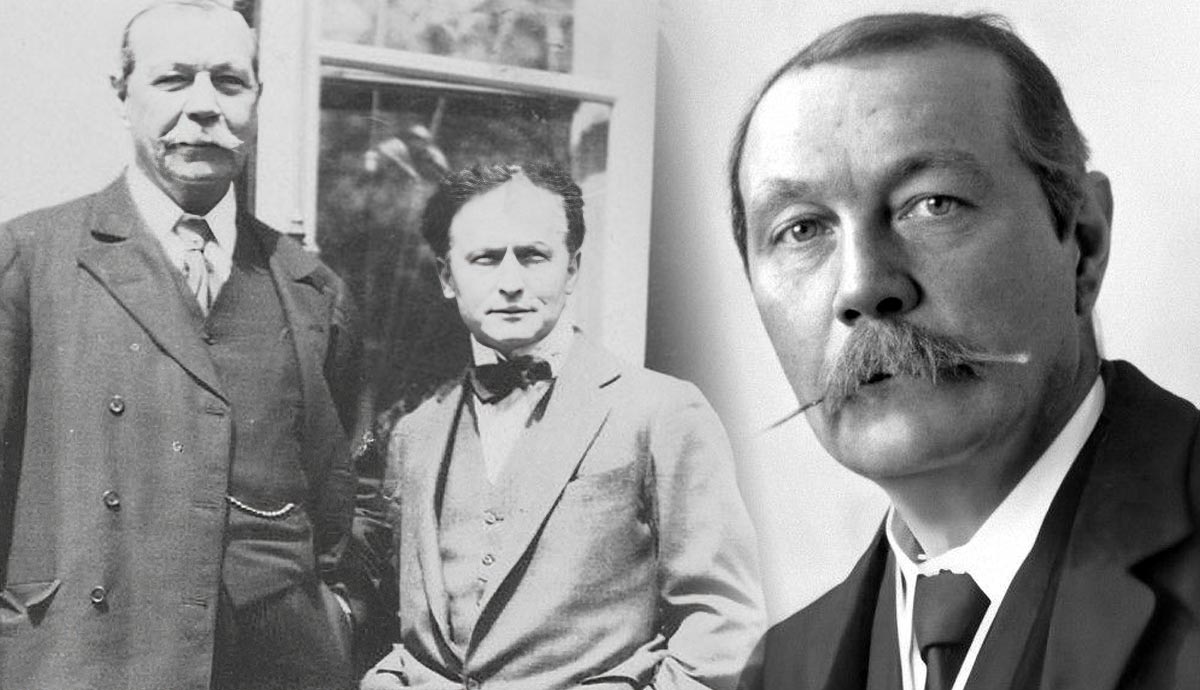

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the author of the Sherlock Holmes series, might seem like the most rational man ever who was capable of coming up with such a logical method of crime-solving. His literary pursuits were not limited to detective stories. Among his other published books were horror stories, history novels, and science fiction pieces. For decades, the writer was also a staunch believer in occult forces, repeatedly stating he was willing to give up his literary reputation for the goal of promoting spiritualism to the masses.

Arthur Conan Doyle & Spiritualism

Before he became a famous writer, Arthur Conan Doyle worked as a well-educated middle-class ophthalmologist. Parallel to his career, he focused on his hobby of studying paranormal phenomena and attending spiritual seances. In itself, this hobby was not entirely unusual for his era. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the Western world lived through a string of mass-scale tragedies, wars, and epidemics that affected almost every family. Doyle himself lost eleven family members near the turn of the century. The desire to connect to the afterlife and see your loved ones at least one more time was understandable.

The demand almost immediately created the supply, with thousands of mediums, telepaths, and fortune tellers ready to provide their services. Numerous psychic societies emerged to study and promote such phenomena. Of course, there was a fair share of skeptics, unwilling to accept the occult explanation, but Arthur Doyle was never one of them.

The famous writer published pamphlets and toured Europe with lectures on the benefits of spiritual knowledge and practice. Raised as a Catholic, he did not see any contradiction in his beliefs, promoting a Christianity-based model of occultism. He participated in several research societies, was a Freemason, and even a member of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, the secret society for occult practitioners. Doyle’s faith in his cause was adamant and stubborn, sometimes landing him in uncomfortable social situations and creating a highly controversial reputation for the writer.

The Cottingley Fairies

Among the most puzzling and ridiculous events in Doyle’s spiritualist life was his role in the infamous Cottingley Fairies Hoax. In 1917, two girls from Yorkshire, England, presented a collection of photographs that supposedly illustrated their communication with fairies. Arthur Doyle was immediately drawn to the case, publishing a series of reports and even an entire volume on Yorkshire fairies. The book The Coming of the Fairies describes the creatures’ social rituals, eating habits, and personalities.

Doyle was absolutely convinced of the existence of the Cottingley fairies, even though the photographs looked revealing enough. The “fairies” looked completely immobile with their wings frozen against naturally moving substances like streams and plants. Doyle became a laughing stock amongst the rationally inclined public and the Catholic church, who accused him of supporting demonic forces.

Several photography experts examined the fairy photographs and proved their authenticity. And they were partially right—indeed, the images had no photomanipulation of any sort. The girls worked with a much more primitive method, simply cutting out fairy figures from a storybook and gluing them to blades of grass. Only in the 1980s, one of the girls, already in her eighties, confessed to the fraud and explained how Doyle’s book made it impossible to stop the hoax from blowing up. Initially, they created the fairy photographs to prank their family, but their mother took it too seriously, launching a series of events that made it impossible for the young girls to reveal the truth without embarrassing themselves.

Doyle and the Greatest Archaeological Hoax

Doyle’s obsession with spiritualism made him the suspect in one of the most scandalous hoaxes in the history of archaeology—the Piltdown Man fraud. In 1912, archaeologist Charles Dawson claimed to have discovered the missing link between apes and humans. In Piltdown, England, Dawson found a human skull with a jaw similar to those of large apes. Dawson’s discovery was met with great enthusiasm since it finally proved Darwin’s theory of evolution. Only in the 1950s could the scientists prove the forgery, stating that the skull was a puzzle made from the remains of three different beings: a medieval human, an orangutan, and a chimpanzee. During the quest for the forger’s identity, Doyle’s name and his occultist affiliations soon attracted suspicion.

Like many Victorian gentlemen, Doyle was an amateur archaeologist and fossil collector. His keen interest found an expression in the novel The Lost World which dealt with a fictional expedition to a South American plateau still inhabited by dinosaurs. In fact, The Lost World was one of the indirect clues to Doyle’s possible involvement in the Piltdown Man hoax.

In the novel, the characters discuss bone forgery several times. This led some investigators to see it as the author’s discreet confession. The writer also lived near Piltdown, played golf nearby, and occasionally drove Dawson to excavation sites in his car. Doyle even had a motif for playing a cruel trick on the scientists. In the years preceding the hoax, he engaged in a bitter feud with researchers who exposed mediums and felt deeply offended. Although Doyle’s involvement in the case hasn’t been proven, some experts see it as an illustration of his staunch and somewhat aggressive pro-spiritualist position.

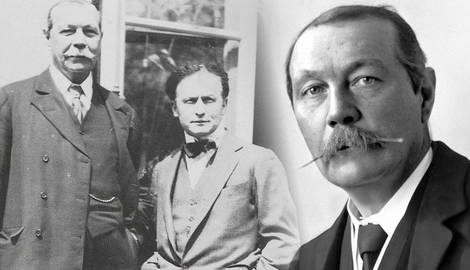

Doyle and Harry Houdini: A Friendship Ruined

Arthur Conan Doyle’s stubbornness in the context of his spiritualist beliefs best revealed itself in his relationship with the famous performer and illusionist Harry Houdini. Houdini was a skeptic, highly critical of spiritualist practices, yet interested in them. He believed that mediums were preying upon the grief and pain of families who lost their loved ones, and he aimed to expose as many of them as he could.

The friendship between Doyle and Houdini was based on rivalry and keen interest in each other. For a while, Houdini saw Doyle as a smart yet confused man and attempted to guide him back to rational thinking. Doyle, curiously, believed Houdini had spiritual powers he preferred to hide from the public. He aimed to expose the illusionist and make him another important asset in his battle to legitimize spiritualism.

Their unlikely friendship came to an end after Doyle’s wife, a self-proclaimed medium, attempted to contact the ghost of Houdini’s mother. In the state of trance, the medium produced fifteen pages of written text, supposedly sent from mother to son. Houdini was not convinced since the letter was completely meaningless and superficial and it contained numerous Christian blessings, despite the fact that his mother lived her entire life as a follower of Judaism.

The incident grew into a public feud, with both sides attacking each other in the press. Houdini became the anti-spiritual activist who called Congress to ban fortune-telling in the USA, and frequently exposed famous mediums. Even after Houdini’s tragic and mysterious death in 1926, Doyle did not stop referring to his deceased friend as a hypocrite who was hiding his mystical power. Perhaps, as a spiritualist, Doyle came to see death as a minor inconvenience rather than a tragedy that put an end to one’s existence.

Arthur Conan Doyle’s Crusade to Legalize Spiritualism

In 1922, Doyle found himself amidst yet another scandal. A group of psychic researchers exposed a fraudulent spirit photographer William Hope by providing evidence of his method of capturing “spirits” on camera. Unwilling to accept this, Conan Doyle flew into a rage and even threatened the researchers by suggesting they might meet the same fate as Harry Houdini. In fact, some historians believe that Houdini’s death was a murder arranged by offended spiritualists.

In 1926, Arthur Conan Doyle published a two-volume book The History of Spiritualism. Dealing with the most remarkable and influential ideas of the movement’s history, it conveniently omitted any research that could have planted a seed of doubt into readers’ heads. At the end of his life, he became increasingly political and aggressive, finally rejecting his Catholic faith and inviting anti-spiritualist theologists to heated debates. He had an ambition to legalize spiritualism as a full-blown and legitimate religion, later turning it into the official religious doctrine of Great Britain. He never came close to realizing his plans. He died in 1930 from a heart attack, with his last notes expressing a concealed yet evident hint of doubt in his life-long beliefs.