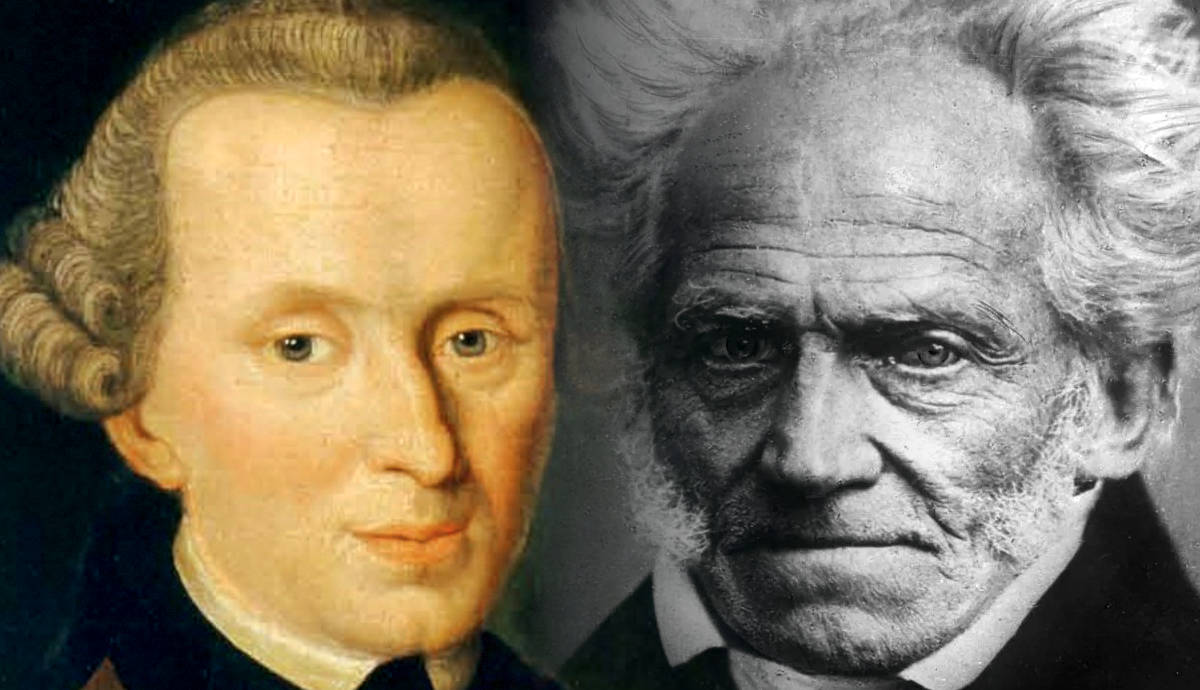

Arthur Schopenhauer is usually mentioned alongside Fichte, Schiller, Kant, and Hegel, his most known contemporaries at the time. However, Schopenhauer bears the greatest likeness to Immanuel Kant. Although Kant was a great inspiration, Schopenhauer still found certain limitations in his tutor’s philosophy. As a result, Schopenhauer came up with an original philosophy. Learn more about how Shopenhauer followed the same path as his tutor, Kant, but arrived to a different destination, and how their philosophies differ.

1. Similarities and Differences in the Metaphysics of Schopenhauer and Kant

As one of the followers of German classical idealism proceeding after Kant’s transcendental philosophy, Schopenhauer strives to understand the world not just from a phenomenological perspective (like Kant did), but also to understand the noumenal world as well.

He accepts Kant’s idea that the world and the whole of reality split into two: the world of phenomenon (how things appear) and the world of noumena (how things are). In this sense, he says that the way we see the world is actually just the human perspective of the way the world really is. He stated that the human mind is “programmed” (relatively speaking) to see and understand the world in a certain way. For example, we cannot perceive a certain object if it is not situated in space and time and if it’s not suffering the cause-and-effect relationship. From this, it does not follow that the things we perceive are as they are in themselves, but it implies that there is some connection between the phenomena and the things in themselves—the noumena.

Although Kant was strongly opposed to rejecting the concept of things in themselves, he still believed that we can know nothing about the nature of such things. According to Kant’s understanding, all human knowledge is limited to the world of phenomena. On the other hand, Schopenhauer aims at identifying the thing in itself, as best as possible.

It is important to remember that for Kant, as for Schopenhauer, the empirical world and the phenomenal world are one and the same and that the forms of such a world are subject-dependent. The phenomenal world is also the world with which science deals. Hence, Schopenhauer accepts Kant’s idea but continues with the investigation of what are the correlations between the world in itself and the world as it is presented to us.

Schopenhauer also accepts Kant’s conception that the “first world,” the world in itself, cannot be known directly. However, he believed that with a detailed analysis of the world of phenomena, we can come to know what the world in itself actually is because, after all, the phenomenal world is a manifestation of the world of noumena. In this way, Schopenhauer indirectly examines the nature of the thing in itself, and this is an important way in which he parts ways with his tutor.

Contrary to Kant, who believed that there is a plurality of things in themselves, Schopenhauer held the view that there can be only one principle as the basis and support of the world of reality. He does this in the following way. He starts analyzing the forms of time, space, and causality. He, like Kant, saw them as extremely dependent and situated in the world of phenomena. However, he comes to the realization that there is no need to separate and distinguish one thing from another since the distinction of things is valid only within the phenomenal world. Such a distinction is only possible thanks to the forms of time, space, and causality, he says.

Furthermore, if such forms are completely extracted from the noumenal world, it becomes a world in which everything is one. In other words, the noumenal world is completely transcendent with respect to the forms of time, space, and causality. Thus the plurality or multiplicity of things is present only in the world of phenomena. From here, he concludes that whatever lies behind the world of representations must be one and undifferentiated.

2. Similarities and Differences in the Epistemology of Schopenhauer and Kant

In identifying the one—the thing-in-itself—Schopenhauer follows Kant’s analysis of how we come to know things. Namely, Kant claims that all knowledge about objects comes to us through the senses, which is further “arranged” by reason, ending in the mind.

At this point, Schopenhauer points out that for each of us individually, there is one object of knowledge to which this conception cannot be fully applicable, and that is our own body. Namely, we obtain knowledge of our body through our senses. However, in addition to this, we have another kind of knowledge that is of a different nature and which does not follow the previous order. Each of us has a large amount of knowledge about this object that does not pass through the senses at all. We actually know that object directly from the inside. Such direct, nonsensuous knowledge of this object of knowledge that comes from within serves as a path to knowledge of the inner nature of things in general, Schopenhauer says. That, he says, is the will.

According to Schopenhauer, every movement of the body is an expression or manifestation of a desire, drive, or impulse of some kind. Although we usually refer to bodily movements as acts of the will, according to Schopenhauer, this is a mistake. There is no such thing as an act of the will that causes or results in a bodily movement. The thought or voice of the will is not the cause of the movement of the body, but the movement of the body is the instant manifestation of the will. Will and physical movement are one and the same thing.

The same applies to other objects in the universe, not only to ourselves, says Schopenhauer. The universe consists of matter in motion, and the matter is actually space filled with energy. Matter necessarily transmutes into energy. What is fundamental and absolute in the phenomenal world is energy, and that is the will. The unknown noumena must be something through which the phenomenal world is manifested. In this sense, the noumenal world manifests itself as energy or rather will, using Schopenhauer’s terminology.

Here, it’s important to point out that on several occasions, Schopenhauer mentions that his use of the term “will” has nothing to do with the conscious activity of man, his life, or his character. There is the same amount of will (energy) in the fall of the stone as there is in the movement of the human body. The whole universe of inorganic nature is a manifestation of will, and the task of physics is to discover the laws, rules, and principles of such movements.

3. A Pessimistic View of the World and Life

Looking through the prism of Schopenhauer’s philosophy, one might come to the conclusion that the world is a horrible place, full of evil, injustice, repression, horror, torture, and eternal suffering. He characterizes the will as a kind of force, an energy that is constantly in motion and action, and which has no purpose or an end goal. That’s why the world we live in is like that, just like life itself. His pessimism comes fully to the surface with the assertion that it would be better for the world not to exist at all than for it to exist as such.

Looking at his pessimistic philosophy as we’ve presented it above, it’s inevitable and almost impossible not to ask ourselves how one can cope with the world of the will. How can we achieve true happiness and bliss? Is such a life even possible? Well, yes. And the answers to those questions lay in the world as representation.

Indeed, despite his pessimistic view of the world and his understanding of life as meaningless, worthless, and filled with constant pain and suffering due to the evil nature of the will, we should still remember that Schopenhauer gives us the world of representations. That is the world in which we attribute meaning to things. Therefore, within this world, Schopenhauer offers a way of occasional escape from constant pain.

That is possible, says Schopenhauer, through aesthetic contemplation of art, creating art, or simply enjoying it. Through art, in fact, we free ourselves from the shackles of the will, from its incessant movement and action that have no purpose at all. Schopenhauer describes the experience of art as an experience in which time stops flowing for a moment, and at that moment, we feel beauty because we are freed from the burden and constant suffocation of the normal state of life.

Among the arts, he values music the most. That’s why he explicitly says: “It is difficult to find happiness within oneself, but it is impossible to find it anywhere else.” (The World as Will and Representation, 1818)

Schopenhauer also mentions another way of coping with the world and dealing with our sufferings in life. That is the concept of turning one’s back on the world and the will or denying the will. This is achieved by complete asceticism or the practice of self-mutilation, which is preached and practiced in several religions. The asceticism of which Schopenhauer speaks consists of passing through several levels or series of levels leading to what Schopenhauer interprets as the complete rejection of the will, the complete extinction of desires and wishes, and the denial of the will to live.

What Schopenhauer has in mind as a form of asceticism is not suicide, but something similar and conceptually close to the idea of Nirvana in Buddhism. The final result of the process of constructive and productive self-denial, as far as we can know, is the negation of being and the experience of a state of non-being or nothingness.

4. An Overview of the Differences Between Schopenhauer and Kant

Schopenhauer, although he followed the tradition of German classical idealism, and specifically Kant, is the only great thinker of Western philosophical thought who draws a parallel between Western and Eastern traditions. We can see that in his concept of the denial of the will.

He is also the first great thinker of Western philosophy to openly state that he is an atheist. He was also one of the great authors of German prose. Many of his sentences are written in such an aphoristic style that they are often taken out of context and published separately in the form of small books as epigrams. Intellectually this is a disaster because it minimizes and completely ignores the fact that Schopenhauer has built a whole system whose philosophy can only be understood as a whole. That’s why a parallel between his philosophy and the philosophy of his “tutor” Kant was essential.

Although it is almost impossible to understand his philosophy completely separated and detached from the philosophy of Kant, in the end, he still built a philosophy of his own, and thus he contributed greatly to the philosophical richness.