Ashurbanipal ruled the Assyrian Empire from 669 BCE – 627 BCE and he is thought to be one of the last great kings of Assyria. As a younger son, he was never meant to inherit the throne. However, the young prince so distinguished himself that his father split his kingdom to ensure that Ashurbanipal would be his successor.

Records of Ashurbanipal’s reign depict a ruler who was both a ruthless warrior and a dedicated scholar. Although he had a significant impact on Mesopotamian history, he garners much less attention than other kings from the region and he is often referred to as one of history’s greatest forgotten kings.

The Assyrian Empire in the Time of Ashurbanipal

The Assyrian Empire originally began as a small city-state under the Akkadian Empire, which dominated Mesopotamia from 2334 – 2154 BCE. After the collapse of the Akkadians, Assyria gradually emerged as an independent political power around the 14th century BCE. Roughly 200 years later, Assyria would suffer a major administrative collapse and lose much of its territory. In the 9th century BCE, about 300 years after its collapse, the Assyrian Empire would re-emerge as a dominant power in Mesopotamia and reclaim its lost lands. By the 7th century BCE, it had reached the peak of its power, becoming the largest empire in the ancient world.

Although the Assyrian Empire began as an Akkadian society, it incorporated several ancient cultures into its social structure as it expanded. Subsequently, Assyria also became one of the most diverse empires in Mesopotamian history. To govern its many regions, the empire was split into designated provinces overseen by governors. In turn, these governors were accountable to the king.

The Assyrians were heavily reliant on military force to maintain control over their vassals and in order to continue expanding their borders. Consequently, the Assyrian Empire dedicated much of its resources to developing military innovations and perfecting the art of psychological warfare, developing into one of the most war-like civilizations in Mesopotamia, often referred to as the first military power in history.

The Younger Son and Heir

Ashurbanipal was born in 685 BCE to Esarhaddon, king of Assyria. Mesopotamian texts do not specify his place in the line of succession, but surviving records indicate that he likely had three older brothers, as well as one older sister, and several younger brothers. In 674 BCE, Ashurbanipal’s eldest brother and the crown prince of the Assyrian Empire suddenly died. Concerned that there would be competition over the succession, Esarhaddon decided to make Ashurbanipal heir to Assyria. Simultaneously, Esarhaddon decreed that his eldest surviving son would become heir to Babylonia. Although this effectively split his empire, Esarhaddon drew up a treaty to secure his plan for the succession. This treaty, often referred to as the Succession Treaty, compelled Assyrian vassals to swear oaths of fealty to both sons and to support their claims to their respective thrones.

Following Esarhaddon’s decree, Ashurbanipal underwent intensive training to be the future king of Assyria. Like other Assyrian kings, his instruction emphasized military skill and the young prince was educated in melee combat, archery, horseback riding, and chariot riding. To prove his military prowess, he was expected to hunt lions and the prince performed so well that he was referred to as the “hunter of lions” in Mesopotamian texts.

Unlike most Assyrian kings, he was also given an academic education by court scholars, who taught the prince to read and write. Ashurbanipal also received extensive political training and even helped to manage his father’s network of spies, which allowed him to increase his knowledge of the Assyrian Empire and to learn about his political enemies. When Esarhaddon left for his military campaigns, Ashurbanipal ran the court in his father’s absence.

The Warrior King

Esarhaddon died in 669 BCE, and the succession proceeded as he instructed. Esarhaddon’s eldest surviving son, Shamash-shum-ukin, ruled over the region of Babylonia while Ashurbanipal inherited control of the remaining Assyrian Empire. Soon after becoming king, he put an end to Assyria’s ongoing war with Egypt and added yet another region to his already massive empire. Following this victory, Ashurbanipal continued the expansionist efforts of his predecessors by waging war with a number of civilizations, such as the Phoenicians and Urartu. One of his most important victories was against the kingdom of Elam, with whom Assyria had battled for centuries until the great king conquered them. Early into his reign, he also put down a number of uprisings from regions that had been recently conquered by his father and still balked at Assyrian rule.

In addition to his successes, Ashurbanipal’s military career was defined by the complete ruthlessness that he showed his enemies. After his armies conquered a region, the king subjected them to heavy plundering and taxation. Defeated populations were often forced to leave their homelands, relocating to other regions of the Assyrian Empire, where they were incorporated into the vast workforce that kept the empire running. Healthy men were also obligated to serve in the Assyrian army. Prisoners of war were subjected to brutal execution methods, such as having their tongues removed and being flayed alive. Some were even put through psychological torture such as being forced to grind the bones of their dead parents, which they believed would have kept their spirits from resting. The king was equally brutal to enemy leaders, subjecting them to public executions or humiliating punishments such as being chained up like a dog outside the gates of Nineveh, the Assyrian capital.

Battle of the Brothers

As planned by Esarhaddon, Ashurbanipal ruled over the majority of the Assyrian Empire. The region of Babylonia was excluded from his control, as Ashurbanipal’s older brother, Shamash-shum-ukin, ruled this portion of the empire. While the two kings appear to have cooperated initially, records indicate that the relationship between Ashurbanipal and his brother soured over time. The exact nature of the conflict is unclear, but records suggest that Ashurbanipal may have tried to control Shamash-shum-ukin’s administration, treating him more like a subordinate governor than a fellow king. In stark contrast, Mesopotamian texts indicate that Ashurbanipal perceived himself as a benevolent king who supported his brother by giving him resources, such as armies and vassals, that were essential to his kingdom.

Predictably, the mounting tensions between the two brothers eventually culminated into open conflict. In 652 BCE, Shamash-shum-ukin formed an alliance with several of Ashurbanipal’s discontent vassals and started a rebellion against his brother. Shamash-shum-ukin’s revolt lasted three years and almost all the southern Assyrian Empire joined the Babylonian army. Despite this, Ashurbanipal and his supporters drove the revolution back, and would eventually lay siege to the city of Babylon for two years. Records of the siege indicate that the situation inside Babylon became so dire that parents cannibalized their own children to avoid starvation. Shamash-shum-ukin died in Babylon when his palace caught fire, possibly in an act of suicide by the king, who would have known what fate awaited him if he was captured.

Revenge

Having lost their king, the Babylonians surrendered. As a king who was completely ruthless in dealing with his enemies, Ashurbanipal had even less mercy for traitors. In his own words, he said, “slit their tongues and brought them low. The rest of the people… I cut down… their dismembered bodies I fed to the dogs, swine, wolves, and eagles, to the birds of heaven and the fish of the deep.” Following the subjugation of Babylon, the king hunted down any surviving leaders who had supported Shamash-shum-ukin’s rebellion. Mesopotamian texts describe that the former rebels were so terrified of Ashurbanipal’s wrath that one king took his own life, while another was overthrown by his people who did not want to be associated with his treason.

Ashurbanipal reserved the most brutal of his punishments for the region of Elam, who had been one of Shamash-shum-ukin’s main supporters. Following his actions at Babylon, the Assyrian King marched on the kingdom of Elam. During the reconquest, his army cut down large portions of the Elamite populace. Those who were not killed were imprisoned, tortured, and forcibly relocated to other parts of the Assyrian Empire.

Many of these cities were also plundered and burned, and their valuables were taken back to the Assyrian capital of Nineveh. Next, the king waged war on Elam for the next decade, eventually raising their capital city of Susa to the ground and subjecting them to total destruction. By the time he was finished, the majority of the Elamite populace had been killed or enslaved, all their cities had been destroyed, and the earth was salted around the cities to prevent them from rebuilding their society.

Ruling the Assyrian Empire

As a result of Ashurbanipal’s military campaigns, the Assyrian Empire underwent significant expansion and added several new regions to the kingdom. These new provinces brought natural resources that were incorporated into Assyria’s economy as well as new citizens who were added to the workforce and army of the empire. Ashurbanipal maintained the administrative system established by his predecessors and ruled through appointed officials.

He distributed his commands through a massive communication network that spanned the entire Assyrian Empire. Mesopotamian texts indicate that Ashurbanipal would also incorporate vassal leaders into his politics, most often by marrying the daughters of leaders who willingly submitted to the Assyrian king. During his reign, the capital city of Nineveh was the largest city in the world, and it is estimated to have been populated by 120,000 people.

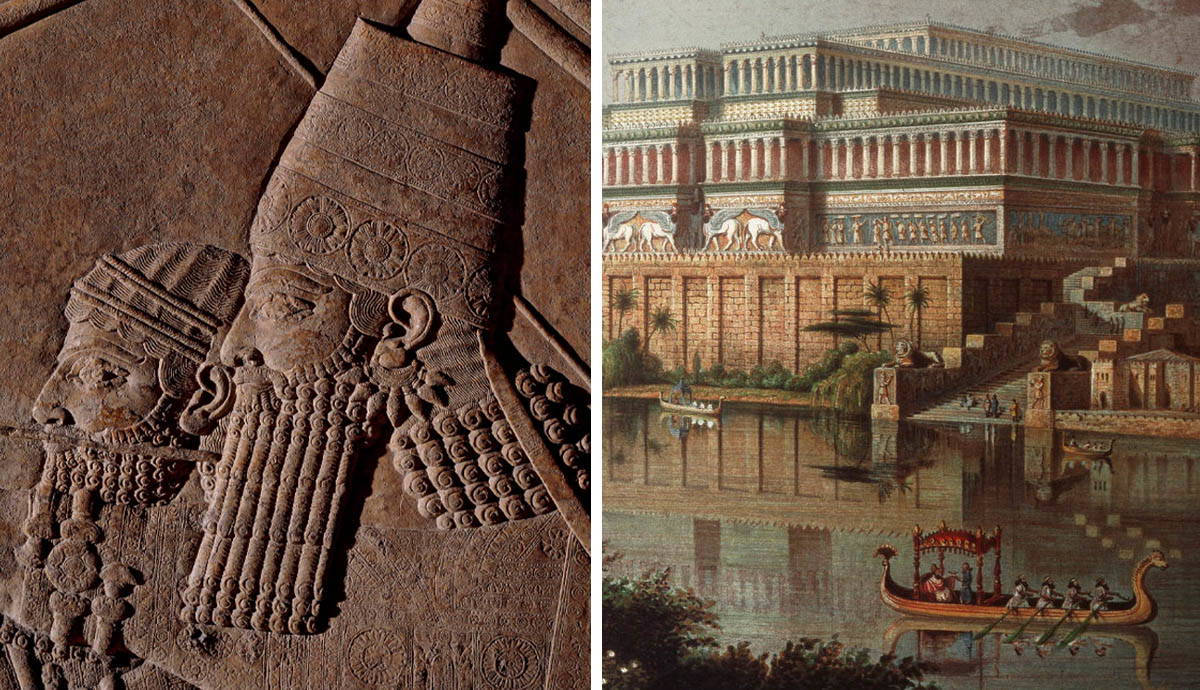

Ashurbanipal was also a patron of religion and the arts during his reign. Several surviving records detail how he dedicated resources to maintaining the shrines of Mesopotamian deities. Ashurbanipal paid particular attention to the main gods and goddesses, such as Ashur, the patron deity of Assyria. However, he also maintained the shrines of lesser deities and even dedicated resources to restoring temples in the regions he conquered. In addition to his support of Mesopotamian religion, the king encouraged the production of art. He combined his support for art and his desire to chronicle his life by commissioning several reliefs and sculptures that depicted various events throughout his reign. Many of these artistic renderings cultivated his reputation as a lion killer and depicted the king in various acts of hunting.

The Scholarly King

In addition to his military career, one of the primary accomplishments that Ashurbanipal is remembered for is his support of academic learning and the preservation of knowledge. Ashurbanipal differed from other kings of Assyria in his ability to read and write, and the education he received as a child appears to have made a lasting impression on him. The king continued his scholarly studies throughout his life, and even commissioned reliefs that depict him carrying a stylus in his belt right next to his sword. As part of his ongoing studies, Ashurbanipal began to collecting clay tablets that contained written stories and information from every corner of his empire. When his collection grew large enough, he created the first library in human history to provide an organized way to store and preserve the knowledge he had collected.

The Library of Ashurbanipal is estimated to have contained 20,000 – 30,000 clay tablets. Although this library was not accessible to the public like modern libraries are, Ashurbanipal did create an organized system to catalog and track everything in his library. Records indicate that he collected the history of past Mesopotamian societies, such as the Sumerians and Akkadians, as well as information about topics such as law, science, and religious dogma.

Some scholars have theorized that Ashurbanipal’s interest in collecting knowledge was also politically motivated, as the information he collected would have given him knowledge and tactics for how to rule that he would not have learned on his own. Additionally, other scholars have pointed out that collecting the written knowledge of the societies he conquered could have been a subtle way to assert his dominance over them as well.

Politics and Propaganda

At first glance, we appear to be presented with opposing perspectives on Ashurbanipal. Records of the way he dealt with his enemies, and even his own brother, arguably portray him as a bloodthirsty tyrant. Written accounts of Ashurbanipal, as well as autobiographies written by the king himself, go into great detail about the horrors he inflicted on anyone that dared to oppose him. Many Assyrian artworks also provide vivid imagery showing how the king crushed his enemies and the punishments he inflicted on them. At the same time, we are presented with a version of Ashurbanipal that respected religious traditions, encouraged the production of art, and advocated for the preservation of knowledge. Correspondingly, the same written accounts that detail the king’s atrocities also describe him as a benevolent and forgiving king.

Rather than providing conflicting accounts of Ashurbanipal, it could be argued that these dualistic perspectives were meant to promote him as a dynamic ruler and solidify his greatness to his subjects. Ashurbanipal consistently described himself as “king of the world” and as being “formed by Assur and Ishtar” to rule. In doing so, he associated his existence with some of the most important deities in Mesopotamian society and, arguably, deified himself to his subjects. Similarly, he used writing and art to portray himself as a ruler who was generous to his supporters and merciless to his enemies. Coupled with imagery that displayed his strength as the “hunter of lions”, the king created an image of himself that was meant to support his claims of greatness by inspiring fear and awe in anyone who knew about him. Similar to his library, the persona that Ashurbanipal cultivated could have been a political tactic to inspire loyalty in his subjects through propaganda.

Ashurbanipal’s Legacy

Although Ashurbanipal successfully expanded his empire and maintained Assyrian dominance during his reign, his methods arguably contributed to his empire’s downfall. Ashurbanipal died in 627 BCE, and within a decade the internal structure of his empire began to collapse. Simultaneously, the Assyrian empire was attacked by a rebellious alliance of Babylonians and Medes. While scholars believe there were several factors involved in Assyria’s fall, the fear that Ashurbanipal inspired in his conquered subjects during his reign could have encouraged them to rebel after his death. In addition, the combined decades of constant war along with the significant expansion of the Assyrian Empire likely put a strain on the internal structure of the civilization. By 609 BCE, less than 30 years after the death of Ashurbanipal, the Assyrian Empire permanently collapsed and would never rise again.

While the great king had failed to ensure the permanence of his empire, he left an indelible mark on Mesopotamia and the rest of human history. Proceeding Mesopotamian civilizations would derive many of their military and political tactics from the Assyrians. Similarly, military innovations and tactics that were first used by the Assyrians, such as professional armies and psychological warfare, would be repeatedly employed by later civilizations such as the Romans and the Mongols.

He also had an impact on modern society, particularly the modern study of history, as many Mesopotamian texts, including the Epic of Gilgamesh, were discovered in the remains of Ashurbanipal’s library. Without these texts, we would know far less about the earliest eras of human history than we do today. As a result of his far-reaching influence on history, Ashurbanipal has come to be known as one of the last great kings of the Assyrian Empire. Arguably, it is poetic that the man who propagandized himself as the warrior “king of the world” made his greatest contribution to the world as a scholar.