The ancient Assyrians have been judged somewhat unfairly as brutal people whose only desire was to conquer their neighbors. Although this is true to some extent, it overlooks the important role the Assyrians played in the history of the Near East. Assyrian kings proved to be equally skilled in the arts of diplomacy and war and they also displayed a keen aptitude for business. The Assyrians used their wealth to build some of the world’s first libraries, which they stocked with religious writings, government records, and some of the most impressive historiographical texts of the ancient world. Also, the palaces of the Assyrian kings were adorned with some of the most inspiring and beautiful art of the ancient world.

Assyrian Merchants and the Old Assyrian Period

The story of ancient Assyria begins with what Assyriologists consider the Old Assyrian period (c. 2000-1800 BCE). It was during this time that the Assyrians established many of the hallmarks of their culture, building their capital city of Ashur on the west bank of the Tigris River. During this era, the Assyrians began to use their skills in commerce to build influence. Assyrian merchants established trade networks throughout the Near East and left behind a cache of written documents in the central Anatolian city of Kanesh. The Kanesh documents relate that Assyrian trade was quite organized, laying the foundation for the intricate trade networks that developed in the Late Bronze Age.

Middle Assyrian Empire

As the Assyrians progressed through the Bronze Age, they used their trade networks to fund the Middle Assyrian Empire (c. 1400-1050 BCE). This was the era when Assyria joined the “Great Powers club” of the Near East with Egypt, Babylon, Mitanni, Alashiya, and Hatti. Assyrian King Ashur-uballit I (ruled c. 1365-1330 BCE) led his people into the club. The Assyrian king wrote an Akkadian language cuneiform letter to the Egyptian king stating the following:

“I send my messenger to you to visit you and to visit your country. Up to now, my predecessors have not written; today I write you. I send you a beautiful chariot, 2 horses, and 1 date-stone of genuine lapis lazuli, as your greeting-gift.”

Assyrian geopolitical influence grew in the Near East, coinciding with Assyrian martial might. By the rule of Assyrian King Tutkulti-Ninurta I (ruled c. 1243-1207), the Assyrians had consumed the Mittanni Kingdom east of the Euphrates River. However, the Assyrian ascent in was temporarily halted by outside forces. Around the year 1200 BCE, the Near East was ravaged by a series of migrations that were led by the mysterious Sea Peoples. When the situation finally settled, the Assyrians and the Egyptians were the only people whose kingdoms would continue into the Iron Age.

Neo-Assyrian Empire

The Assyrians utilized their military prowess to establish what Assyriologists refer to as the Neo-Assyrian Empire (934-610 BCE). The Neo-Assyrian Empire carried on the religious and cultural traditions of the Middle Assyrian Empire, but it proved to be much more advanced on the military front. The Neo-Assyrians employed old yet brutal tactics that included wave attacks, intimidation, the humiliation of defeated peoples, and forced migrations along with a few new technologies. The Assyrians were among the first people in the ancient world to use cavalry, which was a major improvement on the expensive and often unwieldy chariotry. But perhaps the Assyrians’ greatest military innovations were their advanced siege weapons. Pictorial reliefs from Assyrian palaces depict siege towers and shielded, wheeled battering rams, a major improvement on simple ladders.

The Neo-Assyrian Empire fell in 610 BCE when a coalition of states finally managed to bring down the mighty kingdom.

The Assyrians and Israel

One of the greatest impacts the Assyrians had on the Near East, still felt today, was their influence on the Old Testament. Israel was among the many kingdoms conquered by the Neo-Assyrians, although they and many other subject peoples never accepted their subservient role. To reduce the power of the recalcitrant subject peoples, Assyrian King Sargon II (ruled 721-705 BCE) increased the number of provinces in the empire from 12 to 25. King Hoshea of Israel (ruled c. 732-722 BCE) did not like the reduction in his power, so he chose to rebel. The Israelites enticed Egypt to their side, but it was not enough to stop the juggernaut of Assyrian power. The Assyrian historical annals relate that the Assyrians defeated Israel (Samaria), taking many of its people captive.

“I besieged and conquered Samaria, led away as booty 27,290 inhabitants of it. I formed from among them a contingent of 50 chariots and made remaining (inhabitants) assume their (social) positions. I installed over them an officer of mine and imposed upon them the tribute of the former king.”

The Old Testament book of 2 Kings 18:9-11 also relates the siege, although it states that Shalmaneser was the Assyrian king who led the charge. Assyriologists now know that the Assyrian and biblical accounts corroborate instead of contradict each other. It is believed that the siege was initiated by Shalmaneser V (ruled 726-722) and then completed by his successor, Sargon II. The circumstances surrounding the transfer of power remain mysterious, although many believe Sargon II came to power through a coup d’état.

Assyrian Art

Somewhat juxtaposed to the Assyrians’ brutal efficiency on the battlefield and their ruthless diplomatic tactics was their appreciation of art and beauty. Detailed pictorial reliefs discovered in the ruins of Ashur, Nineveh, Nimrud, and other Assyrian cities detail how the Assyrians knew and respected the natural world. In addition to detailed scenes of warfare, many of the reliefs depict large gardens and many animals, especially lions. In many of the scenes, the lions are being hunted and killed by the Assyrian king, but one relief from the North Palace of Nineveh demonstrates that Assyrian artists were not solely obsessed with violence. The scene in question, which is now in the British Museum, in London, depicts a lion and a lioness peacefully relaxing in a garden. Behind the well-detailed lions are equally detailed trees and flowers, giving the viewer a sense of serenity.

Mythological motifs were also common in Assyrian art. Protective spirits were a common theme in Assyrian reliefs, with creatures known as ugallu and urmahlilu serving as the king’s spiritual bodyguards. The ugallu had the body of men and the heads of lions, while the urmahlilu was a human from the torso up and a lion below the waist, similar to the Greek centaur. The Assyrians also depicted mythological motifs, with the winged, human-headed lion creature known as a lamassu being quite popular.

Finally, the Assyrians inherited the Mesopotamian tradition of royal statuary and improved on it. A forty-four-inch high statue of the Assyrian King Ashurnasirpal (ruled 883-859 BCE) is a perfect example of this. The Assyrian love of art and beauty was followed by the Neo-Babylonians who applied many of the same styles. In fact, in The Mystery of the Hanging Garden of Babylon (2015), the British Assyriologist Stephanie Daly argued that Nineveh’s gardens were the true Hanging Gardens of Babylon.

Assyrian Literature

Finally, the Assyrians helped create a culture of learning and literature in the ancient Near East. Although these cultural elements existed before the Assyrians and the Assyrians inherited writing from the Akkadians, they developed religious literature and historiography to a new level. The Assyrians kept thousands of religious cuneiform tablets written in the Akkadian language. The reason why Assyriologists today know so much about Assyrian literature is because the Assyrians were such meticulous record keepers. When modern archaeologists excavated Nineveh, one of the greatest discoveries was the library of Ashurbanipal (reigned 668-627 BCE). The archaeologists found 5,000 cuneiform documents that detailed the affairs of state, religion, and historiography.

In the Assyrian religious texts, the king played a central role as the keeper of the universe’s order. However, even though the king was divinely appointed, he was not divine. The king was a conduit for the gods and goddesses to do as they pleased. The texts relate that the king’s duties ranged from performing common rituals to carrying out war on behalf of the gods. A text from the rule of Ashurbanipal notes:

“(This is) the palace of Ashurbanipal, the high priest of Ashur, chosen by Enlil and Ninurta, the favorite of Anu and of Dagan (who is) destruction (personified) among all the great gods – the legitimate king, the king of the world, the king of Assyria.”

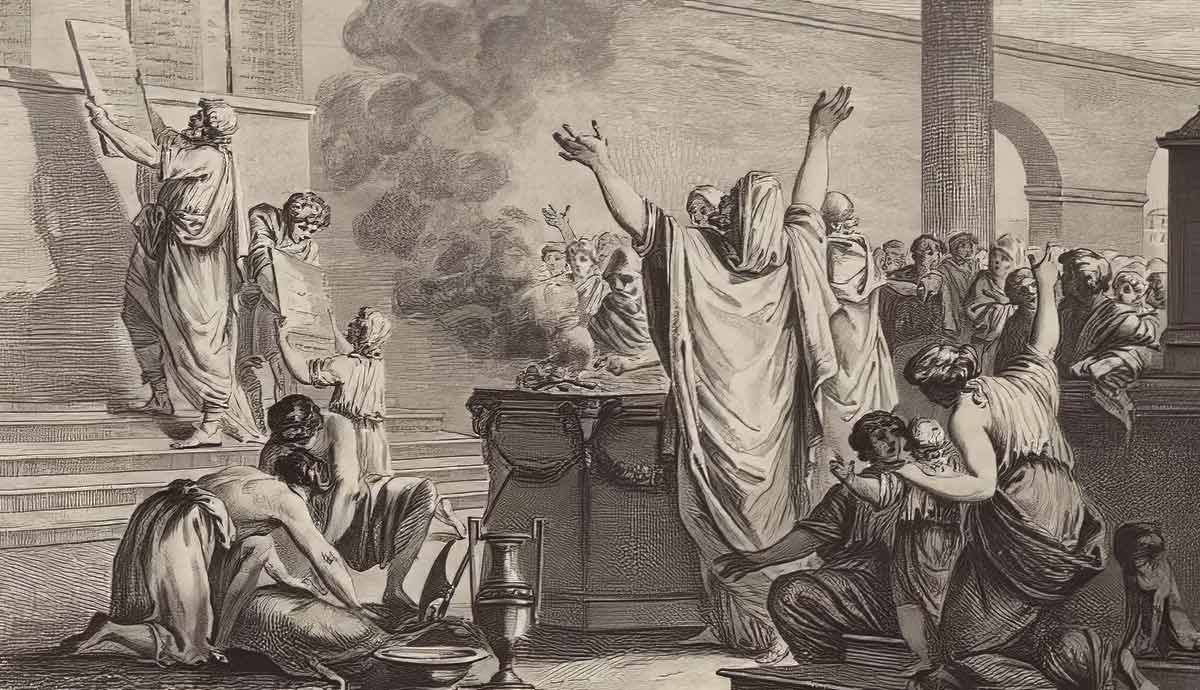

The Assyrians generally followed the same gods as the other Mesopotamian peoples, giving them Akkadian names. With that said, the Assyrians gave prominence to the deities who most closely matched Assyrian values. Foremost in the pantheon was Ashur, the patron god of the eponymously named city, but close behind was Ishtar, the goddess of fertility and war. Other important deities related in Assyrian religious texts include Shamash, the sun-god, and Nabu, the god of wisdom. The texts relate how the king would give offerings to these deities after successful battles as he paraded his captured enemies.

As important as Assyrian religious literature was, the development of Assyrian historiography was even more important. Although historiography (the recording of historical events) was practiced by other Near Eastern cultures before the Assyrians, Assyrian historical records were more detailed and accurate. The Assyrian historical annals were written from the perspective of the king giving a detailed year-by-year account of his military campaigns. The annals were first written during the reign of Tiglath-pileser I (ruled c. 1114-1076 BCE) and continued until the end of the Neo-Assyrian Empire.

In fact, Assyrian annal writing influenced the later Babylonian historiography, namely the Babylonian Chronicle. Assyrian influence can also be found in the Achaemenid Persian historical inscriptions. It should be pointed out that Assyrian historiography was very different than modern historiography. The annals were written as letters from the king to the gods as a theocratic history of a state that properly follows divine laws.

Another genre of historiographical writing that the Assyrians excelled in was king-lists. In the ancient Near East, king-lists were simply ordered listings of the kings of a particular dynasty or kingdom. King-lists were used as far back as the Sumerians and as far away as Egypt, but the Assyrians wrote more complete lists. The earliest of the three Assyrian king-lists began with a semi-mythical king named Tudiya and ended in 722 BCE. Modern scholars, though, are divided over who was the first true Assyrian king. The Assyrians cited Shamsi-adad I (ruled c. 1808-1776 BCE) as their first historically king, although he was an ethnic Amorite and not from Ashur. Some notable modern historians believe that Sulili, who ruled in the late third millennium BCE, was the first true Assyrian king.