Do not touch. These three small words likely make up the most spoken sentence in any museum or gallery, and for good reason. The effects of an inability to resist temptation can be seen in every institution; from shiny-nosed busts in The National Trust manor houses, to the rubbed heads of Roman marble hounds in Italian museums. But has this stringent museum policy negatively affected the way we interact with art? Does some art actually need to be touched to really be experienced? English Modernist sculptor Barbara Hepworth certainly thought so.

Barbara Hepworth And The Importance Of Touch

For Barbara Hepworth, touch was a pivotal part of her practice. Her inspiration came in part from a childhood spent in the vast and dramatic landscape of West Riding, Yorkshire. The artist writes, “All my early memories are of forms and shapes and textures…the hills were sculptures, the road defined the form. Above all, there was the sensation of moving physically over the contours of fulnesses and concavities, through hollows and over peaks – feeling, touching, through mind and hand and eye.” Hepworth always believed that sculpture was at its most essential, a physical, tactile medium. This understanding of what form could be was in the artist almost from birth.

Barbara Hepworth’s life-long belief that sculpture needs to be touched to be experienced was likely strengthened by the Italian sculptor Giovanni Ardini, an early mentor of hers. Meeting him by chance in Rome in her early twenties, he remarked to her that marble “changes color under different peoples’ hands.” This fascinating statement assumes touch as one of the ways a person might be able to experience marble. It also seems to gift equal power to artist and audience (perhaps Hepworth, a committed Socialist, found this unusual stance of equality on such a revered medium a source of inspiration).

Many years later, in a 1972 filmed interview with British Pathe, Hepworth states, “I think every sculpture must be touched…You can’t look at a sculpture if you are going to stand stiff as a ramrod and stare at it. With a sculpture, you must walk around it, bend toward it, touch it, and walk away from it.”

The Direct Carving Technique & The Italian Non-Finito

Since the very beginning of her career, Hepworth, along with her first husband John Skeaping and their friend Henry Moore, pioneered the ‘direct carving’ technique. This technique sees the sculptor work on their block of wood or stone with a hammer and chisel. Each mark made remains very obvious, and highlights rather than hides the original material. The technique was at the time seen almost as a revolutionary act, coming at a time where art schools were teaching their would-be sculptors to model in clay. Works are created that have the very physical presence of the maker left on them.

Hepworth’s Doves, carved in 1927, was made using the direct carving technique. Here, Hepworth is like a magician revealing her tricks. We see the rough-cut marble block and understand the doves as an illusion. But instead of detracting from the magic, this transformation from unyielding stone to smooth and gentle bird is even more astounding. It is hard to resist the temptation to touch, to further understand quite how she has managed this.

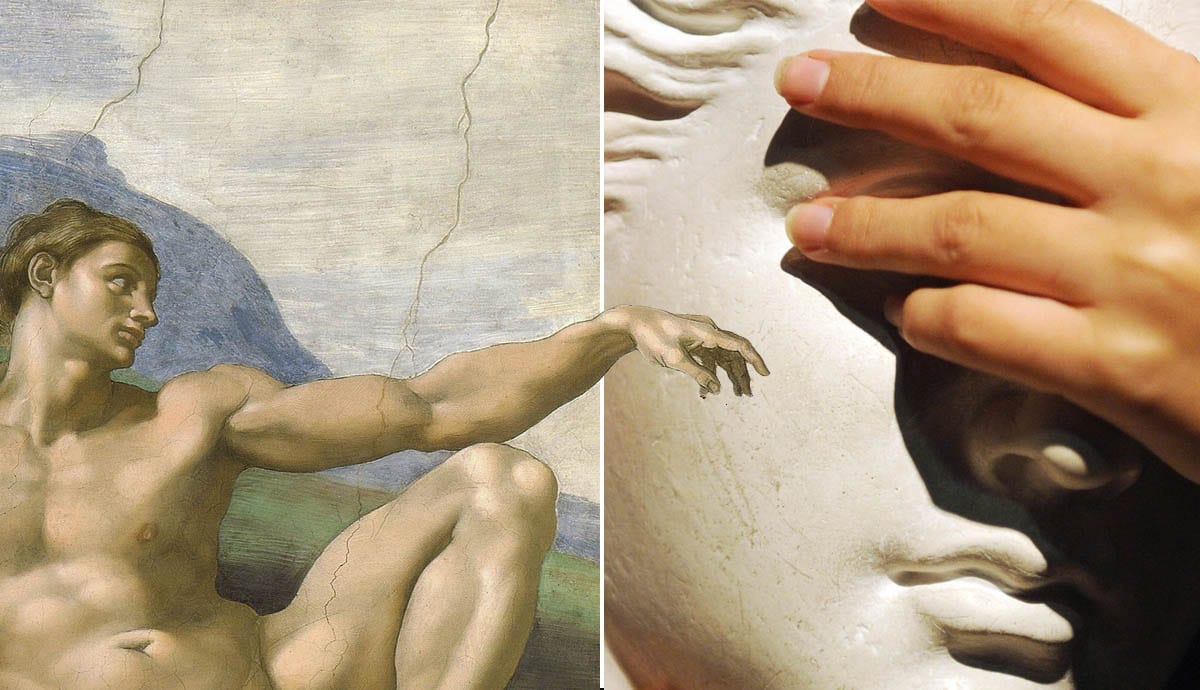

This conscious decision to reveal to the viewer the process, as well as the finished article, lies in the Italian Renaissance, in the practice of non-finito (meaning ‘unfinished). Non-finito sculptures often appear as if the figure is attempting to escape from the block as if they have been waiting inside all along. In the words of Michelangelo, “The sculpture is already complete within the marble block, before I start my work. It is already there, I just have to chisel away the superfluous material.”

Sometime after WWII, Barbara Hepworth embarked on a series of wood carvings, using “the most beautiful, hard, lovely warm timber,” Nigerian guarea. They highlight, more than any other work, Hepworth’s preoccupation with form and play, between inside and outside, between shapes and different textures and tautness. There is something in the contrast between the burnished exteriors and rough, chiseled insides, and the taut string interconnecting both surfaces, that seemed to beg an audience to touch them.

You see, sculpture is a tactile, three-dimensional thing, its very presence demands more of us as viewers than any painting. Henry Moore is another example. One almost wants to curl up with his softly reclining figures. The two rooms in Tate Britain dedicated to the sculptor feel filled with, more than inanimate bodies of stone, relaxed tourists on a beach. You feel as if you have walked into that contented quiet that comes after a long and enormous lunch. There is something in the intimacy of the room that makes it seem alien to be unable to touch them.

Why Is It So Tempting To Touch?

It is important to remember that art and touch isn’t just a 20th-century phenomenon. Ancient talismans, believed to be imbued with particular powers were artworks made to be held and kept close for safety. We still see the importance of touching artworks and objects in religious practice today. Revered icons of Catholic saints are kissed by thousands, the stone carvings of Hindu gods bathed in milk. Superstition also plays a part. The above image shows tourists and new students queuing up to touch the feet of John Harvard, supposedly bringing about good luck.

We know we’re not allowed, so why are there still so many of us who can’t resist the temptation to touch? Fiona Candlin, a professor of museology at Birkbeck College in London and author of Art, Museums, and Touch, cites the following reasons. She argues that touch can enhance our educational experience. If you want to learn about the finish of a surface, or how two pieces are joined together, or what the texture of something is, the only way you can do this is by touch. Touch can also bring us closer to the hand of the maker, and confirm authenticity.

When interviewed by CNN journalist Marlen Komar, Candlin says, “There can be a real blur between museums and experiences and theme parks and wax works. Often if you have really big objects on display — if you think about going into the Egyptian galleries in the British Museum or the Met. Some people can’t believe you would put real things on display without glass around them. They’re not quite sure and they figure if they touch it, they can make an assessment.”

Art touching has undoubtedly gotten worse in the age of the selfie (or if not worse, certainly better documented). There are countless photos floating about on the internet of tourists with their arms over the shoulders of famous figures, patting the heads of marble lions or jokily groping a naked bottom. The latter, in fact, has a historical precedent. The Aphrodite of Knidos by the 4th century BC sculptor Praxiteles was one of the first sculptures of a completely nude female. Her beauty made her one of the most erotic pieces of art in the ancient world. And she caused quite the stir. Ancient writer Pliny tells us that some visitors were quite literally ‘overcome with love for the statue.’ Take from that what you will.

Why Do We Need This Museum Policy?

So, is museum policy selling us short, by not letting us touch the artworks? Realistically, of course, this is an impossible ask. How long would Michelangelo’s David last if every one of those thousands of visitors to Florence laid a hand on his muscular body? You can be sure that that peachy round bum of his would be the first thing to go. Yep, we can look but not touch in this case. For more bumspiration, search up the hashtag best museum bum (#bestmuseumbum). It was trending earlier this year as furloughed curators competed during Covid-19 Lockdown.

But back to the important subject of museums collections care. This primarily focuses on the preservation of artwork and notable objects for years to come. It is done by putting procedures in place to prevent damage and slow the rate of deterioration of artwork and objects. Unfortunately for us, the most common way that works in a collection can get damaged is through human error. However, even without incident, simply by handling and touching, we can easily damage a work. The natural oils and excretions from our skin (however much we wash our hands) are enough to stain the pages of a book, or an antique print or drawing.

Will We Ever Experience Museum Art Like Barbara Hepworth’s Sculptures?

Despite the risks, it is important that collections are handled. Both for the practical purpose of moving items around a museum, but also as a further tool for education. With this in mind, many museums now hold sessions with the objective of handling (some of the less delicate) objects in their collection.

Museums and museum policy are vital in preserving our human and natural heritage. And it’s sometimes too easy to forget that we also have a part to play. So in conclusion, in general, no, we should not touch the art. But when we are looking, we should also never forget that some art was, and sometimes still can be, appreciated by more than just one of the senses.