Baroque architecture originated in late 16th-century Italy. This architectural style developed until the 18th century in regions such as Germany and colonial South America. The baroque style was created with a clear purpose, namely to aid the Catholic Church in winning back the adepts of the Reformation. Because the teachings of most reformed Protestants aimed for a minimalist and clean architectural style, baroque architecture did precisely the contrary. Baroque architecture proposed a rich, fluent, impressive, and dramatic style to visually oppose reformed churches. The buildings take architecture to the next level, both visually and technically, and aim to introduce the viewer to a fantastic realm that evokes the sights of Heaven.

1. Key Elements To Look For In Baroque Architecture

Baroque architecture serves a known purpose, namely that of the aid of the Counter-Reformation. Therefore, it has a clear architectural program that allows for the identification of several characteristics. The main idea behind the baroque is the stimulation of the emotions and the senses. Because the Reformation promoted a rationalized and austere image, the Catholic Church responded by taking the opposite approach. This is why every form and shape from a baroque building targets the engagement of senses and ignites emotions.

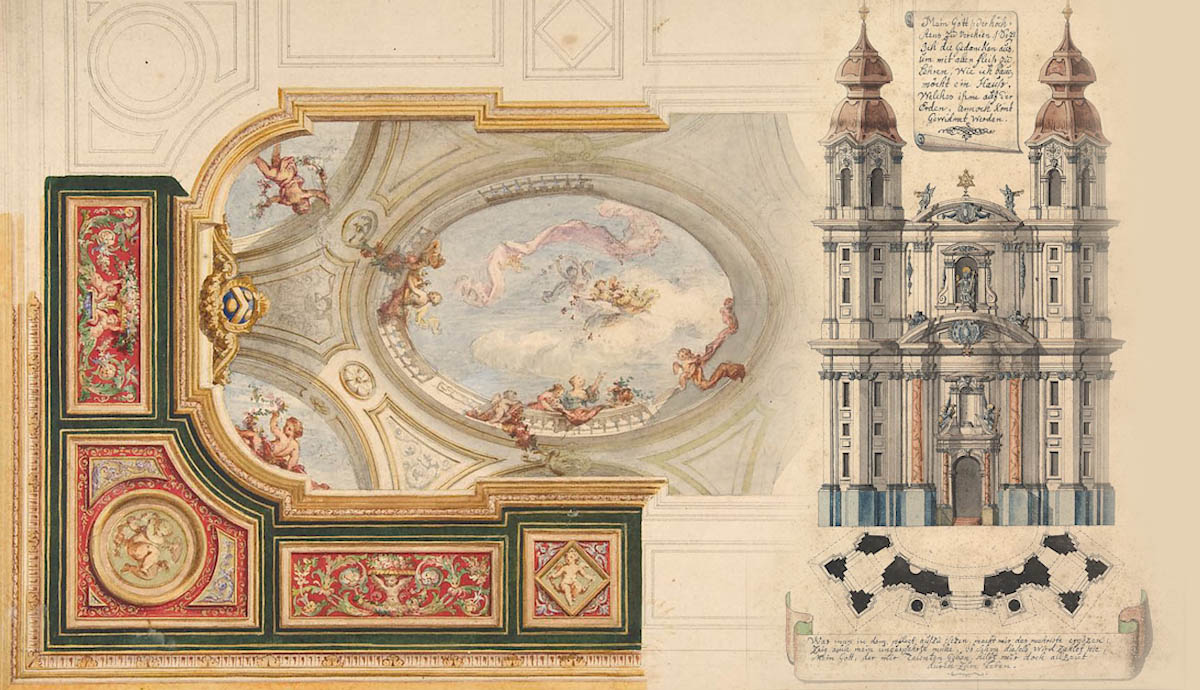

Engaging with the viewer’s emotions is no easy feat; therefore, architectural plans tend to rely on complex shapes: often an oval base and various oppositions of materials and forms that give the building a dynamic aspect. The combination of different spaces is a favorite way of emphasizing motion and sensuality. If the feeling of a building is grand, dramatic, full of contrasting surfaces, a multitude of curves, twists, and gilded statuary, it is likely a baroque building. The interior, in most cases, has a ceiling that is heavily painted, making the viewer believe there is no actual ceiling but rather that the roof is connected to the sky or a divine realm. These characteristics will be discussed in detail in the following points.

2. Famous Baroque Buildings And Artists

Some of the most notable baroque buildings are, as expected, in Italy. St. Peter’s Square in Rome is a popular and partly baroque attraction. Other examples from Rome include the façade of the Il Gesú, the building of Sant’Ivo alla Sapienza, the well-known San Carlo alle Quattro Fontane, and the Trevi Fountain.

From around Europe, some notable examples are the Belvedere Palace, Schönbrunn Palace, and St. Charles Church in Vienna; the Cathedral Santiago de Compostela and Plaza Mayor in Spain; and the Cathedral of St. Paul in London.

Besides these famous buildings, the names of Italian baroque artists Gian Lorenzo Bernini, Carlo Maderno, Francesco Borromini, and Guarino Guarini ought to be mentioned as they were the trendsetters of this style. Moreover, outside Italy, it is worth noting the works of Austrian architects Johan Bernhard, Fischer von Erlach, and English architect Christopher Wren.

3. Everything Flows In Baroque Architecture

With architectural plans that go beyond traditional geometric shapes and often use other inspirations such as letters or combinations of forms imitating a natural element, Baroque architecture is very diverse. Because of the complexity of the plan, there are more opportunities for the architects to play with shapes and forms, all for the sake of visual movement.

Because Baroque architects wished to do the impossible, namely to create movement in the most static form of art, they resorted to curves. Curves and counter-curves became thus the dominant motif of all Baroque architecture and art. Just as in Renaissance architecture, columns were still the main element for the façade of a building. Because of this, artists like Bernini quickly understood that they should make undulating columns in order to give off a dynamic appearance. Bernini’s famous Baldacchino from St. Peter in Rome is an excellent example of this dynamic effect. To go even further in the pursuit of movement, Guarino Guarini began using an undulating order which stood for a system of undulating elements that would create the final appearance of continuous curving.

4. Step Into The Heaven Of Color

Not all historic architecture comprises stone and dull elements, which is especially true for Baroque architecture. Color and painting played an influential role in the complex realization of a building. If Renaissance artists began painting ceilings for patrons, the Baroque took it to another level. During the Renaissance, this was an optional feature; for the Baroque movement, it became a standard. However, painting wasn’t the only type of ceiling decoration used. Wooden ceilings were still in use from the Renaissance but now featured painted or gilded cavities, becoming lacunar ceilings as they would feature an interplay of empty and filled spaces.

When the ceiling was not made out of wood, a rich variation of stuccoes would be used to offer depth. Stucco was made out of plaster with finely powdered marble and which was then modeled and applied on the ceiling, creating a tri-dimensional aspect. Stuccoes were often highly decorated with wreaths of different leaves and plants, geometric forms, and occasionally some human figures such as cupids. What must be stressed here is that the Baroque was a very diverse style that didn’t mind combining different techniques in order to obtain the desired effect. Therefore, a painted ceiling will most likely feature wooden and stucco decorations.

5. The Devil Lies In The Details

If there is an architectural style that thrives in details, that surely is the Baroque. Baroque architecture made extensive use of details its principal mission. Because of this, baroque buildings are often perceived to be overwhelming and otherworldly. One cannot grasp all the details in one view. Everything is assembled to look as divine as if you stepped into Heaven and left the mundane behind.

This dedication to detail is visible everywhere: on the walls decorated with beautiful wooden, marble, and stone sculptures, on the ceiling often vaulted, arched, and painted, and in the small adorned decorations. Baroque architecture makes use of all available materials. The artists and architects employed materials as appropriately as possible in the sense that they used wood for very intricate designs, stone for elements that had to be durable, and marble for the most expensive pieces. Because now the buildings are seen by architects as a single and coherent mass, the decorations played a crucial role in uniting the different parts of a building. Architectural sculptures and vegetal and ornamental motifs become critical elements for helping the eye of the viewer flow from the floor to the walls and up to the ceiling without perceiving them as dislocated from another.

6. The Keyword Of Baroque Architecture: Illusion

Grandeur is the universal word that can describe any baroque building, which brings us to another key feature: illusion. To bring the divine into one’s palace or church, one has to have ample funds that can cover the most expensive materials. However, not everyone could cover the expensive costs of constructing grand Baroque monuments. This is where illusion would come into play: it was a feature that could cut some of the expenses and thus make construction somewhat more budget-friendly. There is a reason why Baroque is jokingly considered among art historians to be a sort of kitsch.

Marble, gold, silver, pearls, and so on were expensive materials one couldn’t always afford to invest into a building. Baroque architecture is highly ingenious as it uses illusion to give the impression of costly materials. For example, at the main altar of a baroque church, there would most likely be a set of grand columns. At a closer look, the viewer would think that they are made out of marble, but in truth, the columns would actually be made out of wood and painted over to offer the visual illusion of marble. This was done so skillfully that the viewer was easily and quite often fooled. Elements of decorations were painted in gold color to give the appearance of real gold, ceilings had painted frames that would give the impression of authentic tri-dimensional frames, and so on. The Baroque played with one’s sight and senses.

7. Trompe L’Œil And Life-Like Appearances

The set of illusions discussed above wouldn’t be enough if the person viewing them would see them as such. Painting techniques, such as trompe l’œil, were used to fool the eye to the point that the person viewing them would wonder: are my eyes deceiving me? The effect of the illusion is absolute if the affected person cannot be certain that what they are looking at is an illusion or not. Indeed, this was the desired outcome. How to win over a guest if not by presenting him with something that will most likely fascinate and baffle him?

The technique of trompe l’œil was a continuation of the Renaissance fascination with perspective. By mastering perspective and developing it to its full potential, painters could uncover new methods to create illusions. The meaning of the technique itself translates to: to deceive the eye. The human figures depicted in a scene using the trompe l’œil technique will offer the sensation that they are getting out of their painting. Trompe l’oeil painting is the type of painting that depicts an object and makes the viewer want to touch it to see if it’s real. Combined with a high interest in life-likeness, the Baroque movement used painted decorations to make buildings become open spaces that reached the heavens.

8. Playing With Light

In theater, light plays an essential role. It can indicate to the spectator if the setting is joyous or ominous, depending on how it is set. Baroque architecture made no exceptions as the style aimed at a dramatic delivery in all of its art forms. How to obtain a dramatic character if not by the manipulation of light?

But how can one direct light in a building? After all, light is not a static painting nor a sculpture. It could be done by the juxtaposition of strong projections, which are complemented by abrupt and deep recesses. Another way of doing this would be by breaking the surface, making it irregular. The main architectural elements that aided in this were the small carved decorations that would shelter both light and shadow in their carvings, giving off from afar the sensation of movement. Another way of accomplishing light manipulation would be by the simple combination of different materials that would create the breaking of surface. Each material takes on light and shadow differently. Therefore, through the use of multiple materials, the architect could create a play of light and shadow with high contrast, just like a Caravaggio painting.

9. Baroque Architecture: Mastery Of Everything

In many ways, Baroque architecture is a culmination of all the existing styles up until its birth. This is why it can be said that it implies a manifestation of ultimate mastery. To be a baroque artisan means to have absorbed all the lessons of ancient, medieval, and Renaissance art in order to deliver something that has its root in their practices yet surpasses their results. Aesthetically, it is hard to dispute what style is more pleasant. After all, this is up to the viewer. However, Baroque architecture offers visual excitement and wonder.

If words are not enough to convince, then the artworks themselves will do it. It is enough to look at the works of Bernini, both in architecture and sculpture, to understand what true mastery means. The Baroque artist can use materials to their utmost potential, becoming a true master of technique. The artistic products of this period make you wonder whether something is genuinely made out of stone or actually alive.