Summary

- A Pivotal Clash: The Battle of Cynoscephalae in 197 BCE marked the Roman victory in the Second Macedonian War.

- Phalanx versus Legion: The battle exposed the weaknesses of the rigid Greek Phalanx against the flexibility of the Roman Legion.

- A Roman Legacy: The victory was the pinnacle of the career of the famous Roman general Titus Quinctius Flamininus.

Since the time of Alexander the Great (336-323 BCE), the Macedonians had dominated the eastern Mediterranean. Their heavy infantry phalanx rolled over the Greek cities and then the Persian Empire. To the west, Roman legionnaires had conquered Italy and were overwhelming Carthage. At the start of the second century BCE, a series of wars pitted these two military machines against each other. After almost two decades of indecisive combat, the first critical clash came in the early summer of 197 BCE at Cynoscephalae.

Before Cynoscephalae: The First Macedonian War

The First Macedonian War (215-205 BCE) was a sideshow to the war between Hannibal’s Carthage and the Romans. Philip V (221-179 BCE) had, by this point, reigned as the young King of Macedonia for six years. So far, he had managed to maintain his dynasty’s influence over Greece but was worried by the emerging Roman presence on the eastern coast of the Adriatic Sea and Macedonia’s western border. As Hannibal defeated Roman armies in Italy, Philip sought an alliance with the Carthaginians. In response, Rome went to war with Macedonia.

Both sides entered this conflict with limited ambitions. The Romans, fighting for their lives in Italy, had few resources to spare and sought only to prevent any assistance from reaching Hannibal. It is unlikely that Philip had ambitions in Italy but instead aimed at removing Roman influence from his borders. The course of this ten-year war reflects these limited ambitions. Philip made some gains in the north but could not expel the Romans. For their part, the Roman contribution was largely limited to their navy, with much of the fighting conducted by Greek allies. This was effective enough to achieve the Roman aim of preventing Philip from aiding Hannibal in Italy.

This first war was a defensive conflict for the Romans. A powerful state had allied with their most dangerous enemy, and they had acted to limit the damage. This war, though, deepened Roman involvement in the affairs of Greece and the Aegean.

Start of the Second Macedonian War

The Second Macedonian War (200-197 BCE) was a short and decisive conflict that saw a direct clash between the full Roman and Macedonian armies. Its origins lay in disputes that did not, and need not, have directly involved the Romans.

In 202 BCE, in what would be known as the Fifth Syrian War, Philip’s campaigns east of Macedonia in the regions of Thrace and Asia Minor (north-west Turkey) brought him into conflict with the Kingdom of Pergamon, a Roman ally, and the island of Rhodes. A seemingly minor incident of alleged religious sacrilege at Eleusis widened the conflict to Athens and prompted Macedonian raids on the city. While the King of Pergamum would deal a crushing defeat to the Macedonians at the Battle of Chios, the Rhodians, Pergamon, and the Athenians appealed to Rome. Initially, Rome would only send envoys to Greece to form a coalition against Macedon, which Philip took as a sign of weakness and license to continue his campaigns.

The year 200 BCE saw Philip inflicting heavy damage on the countryside around Athens while a Roman fleet raided the key Macedonian base of Chalcis on the island of Euboea. In the following year, Rome and its allies, now including the Aitolians and King Amynander of the Athamanians, pressured Macedonia’s borders without making a breakthrough. With no change in Philip’s behavior, despite some reservations from a war-weary populace, the aristocratic Roman Senate called for war. And so, Rome’s second war against Philip and the Macedonians began. The Romans could claim this was to defend their allies, but the rulers of Rome embraced the opportunity for war.

Enter Titus Quintcius Flamininus

The war turned with the appointment of Titus Quinctius Flamininus to the command of Roman forces. Ambitious, capable, and energetic, Flamininus had risen to Rome’s highest office, the consulship, before the age of 30. He was born into an aristocratic family active in politics since at least the 4th century BCE. His grandfather had been a famous flamen Dialis, or head priest, of the principal Roman god Jupiter, earning his family the prestigious cognomen Flamininus.

Falamininus was serving in Tarentum in southern Italy under his uncle in 205 BCE, a city that had been fortified because it had previously defected to Hannibal. When his uncle died the same year, despite being just 25 years old, command of the garrison was transferred to Flaminimus. During his three years there, he became familiar with the Greek language and culture. In 201-202 BCE, he was one of a commission of ten men charged with settling Scipio Africanus’ veterans in Southern Italy, which gave him the opportunity to enhance his reputation with the Roman people.

This fueled Flamininus’ successful run for consul in 199 BCE to hold the position in 198 BCE. The official ages set out by the Roman cursus honorum had not yet been defined, but running before the age of 30 was still highly unusual. Even the famous Scipio Africanus first earned the consulship at the age of 31. His candidacy was initially vetoed by two Tribunes of the Plebs on account of his youth, but the Senate forced them to remove their veto and allow him to stand. He was elected in second place after his colleagues Sextus Aelius Paetus Catus, but due to Catus’s lack of military experience, the Second Macedonian War was assigned to Flamininus.

Wasting no time, Flamininus set off to take command at the first opportunity. Speaking Greek and presenting himself as a lover of Greek culture, Flamininus was able to win friends and dispel the fear of the Romans as barbarians that had built up following some brutal Roman acts in recent years. Soon Philip’s key Greek ally, the Achaians, defected, leaving the Macedonians with few remaining friends.

A first attempt at peace in 198 BCE failed as Philip could not accept Roman demands, which would have severely reduced Macedonian influence. Flamininus inflicted a defeat on Philip at the river Aous, significantly damaging the Macedonian army and forcing the king to retreat. Meanwhile, Roman and allied forces continue to pressure Macedonian positions in the Peloponnese and on Euboea. By the start of 197 BCE, the war was going badly for Philip, but he was far from defeated. The matter would have to be settled in a head-to-head battle.

The Campaign of 197 BCE

In the spring of 197 BCE, the Roman and Macedonian armies moved towards each other. With its Greek allies, the Roman army was probably around 30,000 strong. Of these, around 18,000 were Roman legionnaire infantry, including veterans of the Punic Wars. In addition, the Romans boasted a force of 20 war elephants.

Philip’s army was likely a bit smaller, at around 25,000. The resources of his kingdom seem to have been stretched by the recent wars. For this campaign, he had been forced to call up teenagers and those older than 55 to fill in the gaps. In contrast to the Roman force, Philip was leading an army with a considerable number of inexperienced soldiers.

The early summer saw these two armies manoeuvring in southern Thessaly. Aware that Philip’s resources were at their limit, Flamininus’ moves aimed at blocking his access to supplies by cutting the road to the Macedonian base of Demetrias on the coast. After an inconclusive skirmish, Philip headed west to seek supplies around the town of Scotussa. Flamininus followed to prevent Philip from resupplying. Both armies were now marching west to the same destination.

A range of hills separated the two armies, making them unaware of each other’s presence. A storm and low, thick mist reduced visibility further. When scouts from the two armies started coming across each other in the mist around the hills known as Cynoscephalae (dog heads), few expected that the day would bring the decisive and long-awaited clash between the Macedonian phalanx and the Roman legion.

Phalanx Versus Legion

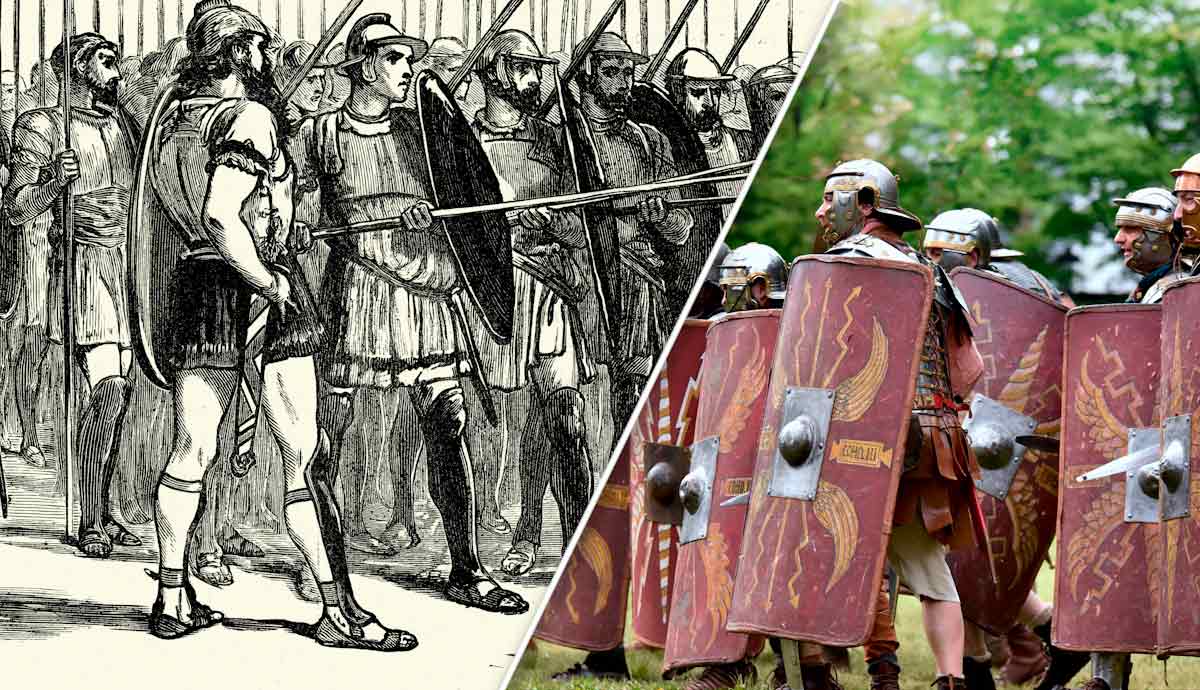

For a hundred and fifty years, the Macedonian phalanx had crushed everything before it. Philip II of Macedon had created an army that his son, Alexander the Great, used to conquer the Persian Empire. At its core was the phalanx, a densely packed body of soldiers wielding an 18-foot pike known as a sarissa. The length of the sarissa allowed five spear points to project out in front of the first rank of soldiers, presenting the enemy with moving walls of spear points. Massed in formations 16 men deep, this wall of spears was virtually unapproachable and unstoppable once it got moving. This collective was extremely strong, but the individual soldier (a phalangite) was weak. The length of the sarissa meant the phalangite could only carry a small shield and sword or dagger. If their formation was broken, they were dangerously vulnerable. Therefore, the phalanx had to be deployed on suitably level ground.

The Roman legion of roughly 4,500-5,000 men was highly organized and divided into a variety of sub-sections rather than deploying as a single mass. They often went into battle in three lines, organized according to each rank’s experience. Each legionnaire was heavily armed and armored with a large shield, javelins, and a short stabbing sword. In contrast to the phalangite, a legionnaire could defend himself and would not be daunted by being divided into smaller groups.

The two armies stumbling toward each other in the mist at Cynoscephalae would finally bring about the direct confrontation of these two different systems.

The Battle of Cynoscephalae

Though long anticipated, the battle that took place surprised both commanders. The first scouts confronting each other in the hills gradually drew in more units, creating a significant skirmish. As Philip reached the top of the range of hills, he was presented with a problem.

The Cynoscephalae hills, described at the time as “rough, precipitous and of considerable height” (Polybius 18.22), were not the smooth level ground suited to the phalanx. Nor was Philip’s army in position. Not anticipating a battle, part of his force had been sent out to look for supplies. The king was assembling a powerful force around him, but to his left, his units were still marching up. However, if Philip did nothing, he risked losing the forces currently engaged, which would weaken his already smaller force.

At various points in his career, Philip had acted courageously and decisively, and after some hesitation, he decided he had to act now. He ordered his phalanx to deploy and to double its ranks from the usual 16 deep to 32, creating a tightly packed and powerful attacking force. The Macedonian left flank under Nicanor was ordered to come up as quickly as possible. Flamininus brought his main forces into position to prepare for the attack.

Both sides charged at each other on the right-hand side of the battlefield. With sarissas lowered and coming downhill, the Macedonians began to push back the Roman left. Seeing his forces retreat, Flamininus reacted by switching attention to the other side of the battlefield. The Roman right, led by 20 war elephants, attacked the Macedonian left and caught them before they were prepared. Upon the hills, the phalanx could not deploy correctly, and the whole Macedonian left wing was defeated.

The day so far had been two separate battles. On the right, Philip was winning. On the left, Flamininus was equally triumphant. What swung this delicate balance was an unnamed Roman officer. Seemingly on his own initiative, a Roman tribune led 20 maniples (small units of around 120 men) from the advancing Roman right and turned on Philip’s soldiers. Having pushed up the hills in pursuit of the Macedonian left these Romans now attacked downhill into the vulnerable flank and rear of the phalanx. On the verge of victory shortly before, these phalangites were now practically defenseless, unable to turn their sarissas around or change formation. The Romans cut them down mercilessly.

Philip, seeing his soldiers cut down in front of him and his left wing defeated, pulled together what survivors he could and fled the field. 5,000 Macedonians were reported captured, and around 8,000 killed. The Romans are said to have lost about 700 men. The long-awaited clash between legion and phalanx had resulted in a decisive victory for the Romans.

Aftermath of the Battle of Cynoscephalae

Reflecting on this battle, and the decisive Battle of Pydna between the Romans and Macedonia in 168 BCE during the Third Macedonian War, the Greek historian Polybius sought to understand the result (Polybius 18.28). After all, the Macedonian phalanx had dominated the battlefield for more than a century. The Greeks were shocked that it could be defeated in open battle, while Philip himself seems to have believed in the power of his army right up until the day of battle.

Polybius found that the vulnerability of the phalanx was its inflexibility. It was a powerful method of warfare, but one that could only work on certain battlefields. The Roman army, by contrast, was more flexible. It was not a dense mass, only able to move in one direction. Its units could split up, change direction, and deal with obstacles thrown up by the ground. A legionnaire could fight on his own. A Macedonian phalangite could not. As was seen in the battle, Roman officers were able to use this flexibility to take the initiative. Without orders from his commander, a lower-ranking Roman officer won the battle and the war. By contrast, the Macedonian left was disorganized and quickly defeated in the absence of Philip.

Cynoscephalae could be seen as an event decided by contingent factors. The vagaries of weather, terrain, and individual decisions resulted in a Roman victory. But as Polybius recognized, the result was made possible by the contrasting systems of the Macedonian phalanx and Roman legion. This would be proven again in the coming decades as the Macedonian wars continued.

The wars would continue, but in the aftermath of Cynoscephalae, Philip was given relatively lenient terms due to the help he offered the Romans during the Roman Seleucid War in 192-188 BCE. Nevertheless, the Macedonians were constrained to their traditional borders and stripped of all Greek possessions, but the kingdom of Macedonia remained intact. Philip would slowly and skillfully rebuild his strength over his remaining years. Flamininus solidified his favorable position in the eyes of the Greeks by declaring them free from their long Macedonian captivity.

That freedom, though, was strictly limited, and it would not be long before Roman legions were once again marching in Greece and Macedonia. The Third Macedonian War raged between 171-168 BCE, ending with the decisive Battle of Pydna and seeing Macedon and its territory divided into client kingdoms. The Fourth Macedonian War of 150-148 BCE saw Macedon annexed directly as a province. Following the Achaean War in 146 BCE, the rest of mainland Greece was annexed as a Roman Province.