Egypt had a longstanding interest in the Levant, where it had established several buffer provinces under the control of its vassals, possibly in response to earlier conflicts with the Hyksos. This region was, however, highly coveted by the “Great Powers” of the Near East. The Kingdom of Mitanni worked against Egyptian influence in the land of Amurru, near the Egyptian-Hittite border. Many of the local Canaanite rulers were induced to rise in revolt against the Egyptians with the support of the Mitanni. The new ruler of Egypt, Pharaoh Thutmose III, considered such a loss of Egyptian power and prestige unacceptable. As a result, the two sides would clash at the Battle of Megiddo (1457 BCE).

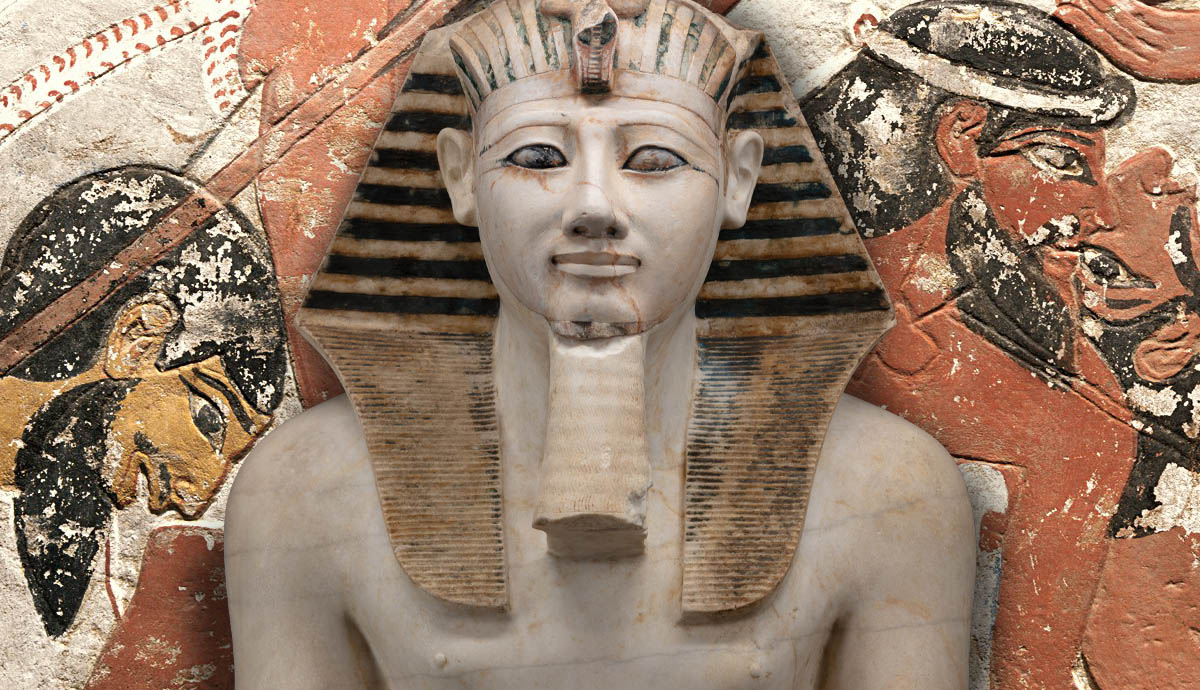

Hatshepsut & Pharaoh Thutmose III: Towards the Battle of Megiddo

At the time of the Battle of Megiddo (1457 BCE), Egypt was ruled by the Pharaoh Thutmose III, who had recently become the empire’s sole ruler. Thutmose III had, in theory, ruled Egypt since the age of two as his father Thutmose II had died in 1479 BCE. In reality, power had rested in the hands of Thutmose III’s stepmother and aunt Hatshepsut. A dynamic and powerful ruler in her own right, Hatshepsut developed Egypt’s trading networks, oversaw an extensive building program, and sent raiding expeditions into the Levant and Sinai. For nearly two decades, Hatshepsut served as regent and co-ruler with Thutmose III, who, in time, became the supreme commander of Egypt’s military. As a result, he became intimately familiar with the theory and practice of war so that as Pharaoh, Thutmose III became one of Egypt’s greatest military leaders.

Scholars have long thought that the relationship between Hatshepsut and Thutmose III was strained and that Thutmose III hated her for exercising power for so long. This theory is largely based on the later erasure of Hatshepsut’s name from many public monuments. In recent years this theory has been questioned as the tombs of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III were built next to each other and the erasure occurred late in Thutmose’s reign, meaning that as commander of the military, Thutmose III could have just seized power. Instead, it is thought that Thutmose III was trying to weaken the power and influence of Hatshepsut’s family and relegate her to a role more in line with what was traditionally expected for Egyptian women.

The “Great Game” in the Ancient Near East

At the time of the Battle of Megiddo, the Ancient Near East was dominated by a number of powerful kingdoms and city-states that vied with each other for power and influence. The most powerful of these were the Hittites, Mitanni, and Kassites. These states were ruled by Indo-Aryan military elites who had taken over from the local dynasties. Closely tied to each other, the Hittites, Mitanni, and Kassites nonetheless struggled to rule the ethnically diverse lands of the Ancient Near East. However, although many of the city-states in the region were powerful, none could truly challenge the might of these great powers.

The only non-Indo-European state capable of challenging the Hittites, the Mitanni, and the Kassites was Egypt. Recently emerged from a period of weakness after expelling the Hyksos, the Egyptians campaigned extensively across Syria and the Levant. These campaigns brought trade and riches to Egypt as the local Canaanite city-states were reduced to the status of vassals. As Egyptian influence spread north, the Mitanni were also engaged in expanding into the region. This resulted in growing competition between the two powers. Initially, many city-states in the Levant had surrendered to the Egyptians without resistance but now the prospect of support from the Mitanni made resistance possible.

Canaanite Coalition

With support from Mitanni, Egypt’s Canaanite vassals waited for the right moment to rise in revolt and shift their allegiance. They did not have to wait long, for Hatshepsut died in late 1558 BCE and was succeeded by the largely untested Thutmose III. There were many advantages in launching their revolt during the interregnum as the transition would slow the Egyptian response. According to the Egyptian sources, the driving force behind the revolt was the powerful Canaanite king of Kadesh. The king of Kadesh gathered an allied army of 10-15,000 Syrians, Arameans, and Canaanites. However, his most important ally was the Canaanite king of Megiddo.

The city of Megiddo was of great strategic importance for the Canaanite coalition. It was located along the southwestern edge of the Jezreel valley just beyond the Mount Carmel ridge in modern Israel. From this position, Megiddo dominated the Via Maris (Way of the Sea), which was the main trade artery between Egypt and Mesopotamia. The city also possessed strong fortifications and overlooked a fertile valley making it an ideal spot to concentrate a large army. Simultaneously the Canaanites were also able to severely restrict Egyptian trade while shielding the allied cities to the north from the Egyptian army. The Canaanites had certainly done very well choosing their position for the Battle of Megiddo.

The Roads to Armageddon

In Greek, “Megiddo” was rendered as “Armageddon,” which due to its theological importance, has become a byword for the end of the world. The road from Egypt to Armageddon and the Battle of Megiddo was in 1457 BCE a long and treacherous one. After assembling an army of some 10-20,000, Pharaoh Thutmose III marched from Egypt to Gaza and then to the city of Yehmen. At Yehmen, Thutmose III sent out scouts to determine the best route forward. According to their reports, there were three routes forward from Yemen to Megiddo. The northern and southern routes were deemed suitable for the army to traverse, although they added more time and distance to the march. There was also a central route through a ravine which, while considerably shorter, was also exceedingly narrow. According to the scouts, it was so narrow that the soldiers would have to march single file. If the Canaanites caught Egyptians marching through the ravine, there was a real danger that the whole army could be destroyed.

Meeting with his generals to discuss their options, Thutmose III made the decision that would win the Battle of Megiddo. Since his generals had advised taking the safer routes, Thutmose III assumed the Canaanites would also deem the central route unsuitable for an army. As such, he decided to do the unexpected and risk his army by marching through the central route. The king of Kadesh had indeed arrived at just such a conclusion and split his forces to cover the northern and southern routes. By comparison, the central route was covered by no more than a handful of sentries.

Battle of Megiddo

In order to maximize his chances of success, Pharaoh Thutmose III opened the Battle of Megiddo by leading a picked force through the narrow central route. The Egyptians caught the Canaanite sentries by surprise and quickly overwhelmed them. With the route now secure, the rest of the Egyptian army followed and marched into the Jezreel valley, where it set up camp. The way to Megiddo was now open and the Canaanite forces were far away to the northwest and southeast. Caught by surprise, the king of Kadesh rushed his forces back towards Megiddo, where they began to take up position on some high ground near the fortress. During the night, Thutmose III left a small guard at the Egyptian camp and marched his army close to the Canaanite position. The following morning, the Battle of Megiddo began in earnest.

It is unclear whether or not the king of Kadesh was able to fully prepare his army in time for battle, though they did enjoy the advantage of holding the high ground. Thutmose III arranged his army in a concave formation consisting of three divisions. This allowed the Egyptians to threaten both flanks of the Canaanite army. At this stage of the Battle of Megiddo, both the Egyptians and Canaanites are estimated to have had around 1,000 chariots and 10,000 infantrymen. Thutmose III commanded the center division of the Egyptian army which launched an immediate and ferocious attack on the Canaanites just as the Egyptian left division enveloped the Canaanite flank. This was too much for the Canaanites, who were quickly overwhelmed after a short but sharp engagement. In the fighting, some 4,000 Egyptians were killed and another 1,000 wounded, while Canaanite losses amounted to 8,000 killed and 3,400 wounded. Those closest to the city of Megiddo rushed inside and shut the gates, trapping the rest of the Canaanite army outside. The Egyptians had won the battle of Megiddo, but their victory was not as decisive as it could have been.

Aftermath of the Battle of Megiddo

With the Canaanite forces in full retreat, the Egyptian soldier quickly began to loot the Canaanite encampment. This allowed many of the Canaanites to escape into the city. Many, including the king of Kadesh, were hoisted into the city on ropes lowered over the walls. By not pursuing the Canaanites more closely in the aftermath of the Battle of Megiddo, the opportunity to capture the city and inflict a more decisive defeat was lost. The Egyptians were forced to lay siege to Megiddo for seven months, during which time the king of Kadesh managed to escape. When Megiddo finally capitulated, its king and citizens were spared, but they had to render tribute to Pharaoh Thutmose III. The temple walls at Karnak record the booty taken at the Battle of Megiddo as consisting of 924 chariots, 200 suits of armor, 502 bows, 340 prisoners, six stallions, 2,041 mares, 19 foals, 1,929 head of cattle, and 22,500 sheep, along with the armor, chariot, and tent of the king of Megiddo.

The Egyptian victory at the Battle of Megiddo brought all of northern Canaan under Thutmose III’s control and the Canaanite and Syrian princes were obligated to send tribute to Egypt. They were also forced to send their sons as hostages, who were raised and educated to have pro-Egyptian sympathies. Other great powers in the Ancient Near East, such as the Hittites, Kassites, and Assyrians, sent Thutmose III gifts of congratulations for his great victory in the Battle of Megiddo. However, since the king of Kadesh had escaped, Thutmose III still had to fight him and the Mitanni for many years. Although the Egyptians were able to conquer large swathes of Syria and ravage the lands of both the Mitanni and Kadesh, they were never able to completely destroy either.

Battle of Megiddo: The Legacy

Thanks to Pharaoh Thutmose III’s victory in the Battle of Megiddo, the Egyptian Empire was able to reach its greatest extent. The threat to Egypt’s territory, prestige, and influence, though not completely eliminated, was severely diminished. This brought untold wealth into Egypt through both booty and trade, which helped ensure that the Egyptian “New Kingdom” was one of the most prosperous periods in Egypt’s history.

Today all of the details concerning the Battle of Megiddocan be found in the hieroglyphics decorating the walls of the Hall of Annals in the Temple of Amun-Re at Karnak where they were recorded by the military scribe Tjaneni. During the campaign that resulted in the Battle of Megiddo, Tjaneni served as Thutmose III’s personal scribe and appears to have kept a daily journal. The Battle of Megiddo was recorded in at least somewhat reliable detail. This was also the first battle for which there is a recorded casualty list and the first recorded use of the composite bow in war. The Battle of Megiddo also eventually helped give us the word “Armageddon,” which took its root from Megiddo. For the Canaanites and their Mitanni allies, the Battle of Megiddo must have undoubtedly felt like Armageddon.