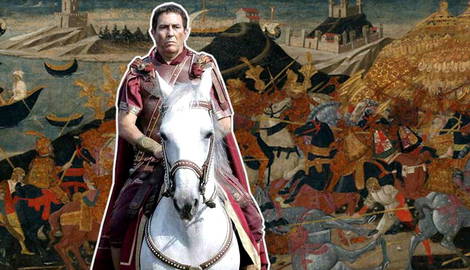

On August 9, 48 BCE, two massive armies faced each other. On one side, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus (also known as Pompey the Great) led an army numbering as many as 52,000 soldiers. They held the high ground and the numerical advantage over their rival. Facing them was the army of Gaius Julius Caesar outnumbered two to one.

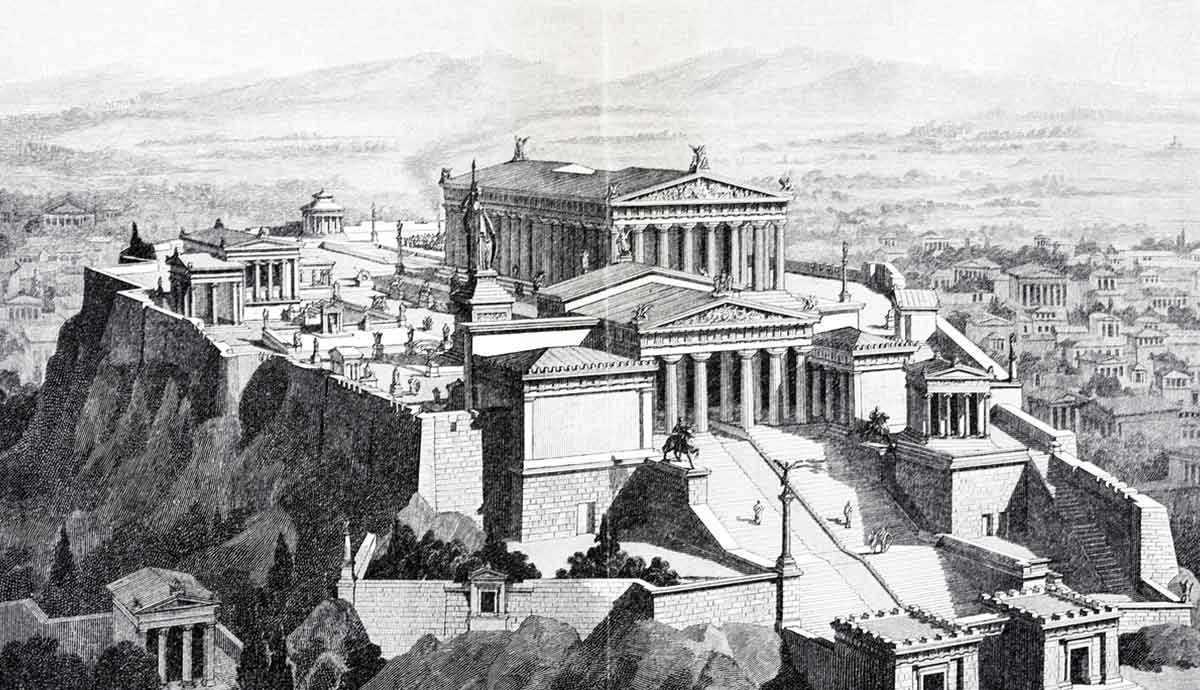

What followed would be one of the bloodiest days in Roman history as national compatriots slew each other, and the two generals, once friends, would seek to strike a final nail in the other’s coffin. The result of the Battle of Pharsalus, on the southern edge of the Thessalian Plain in Greece, would determine the future of Rome.

Background to the Battle of Pharsalus

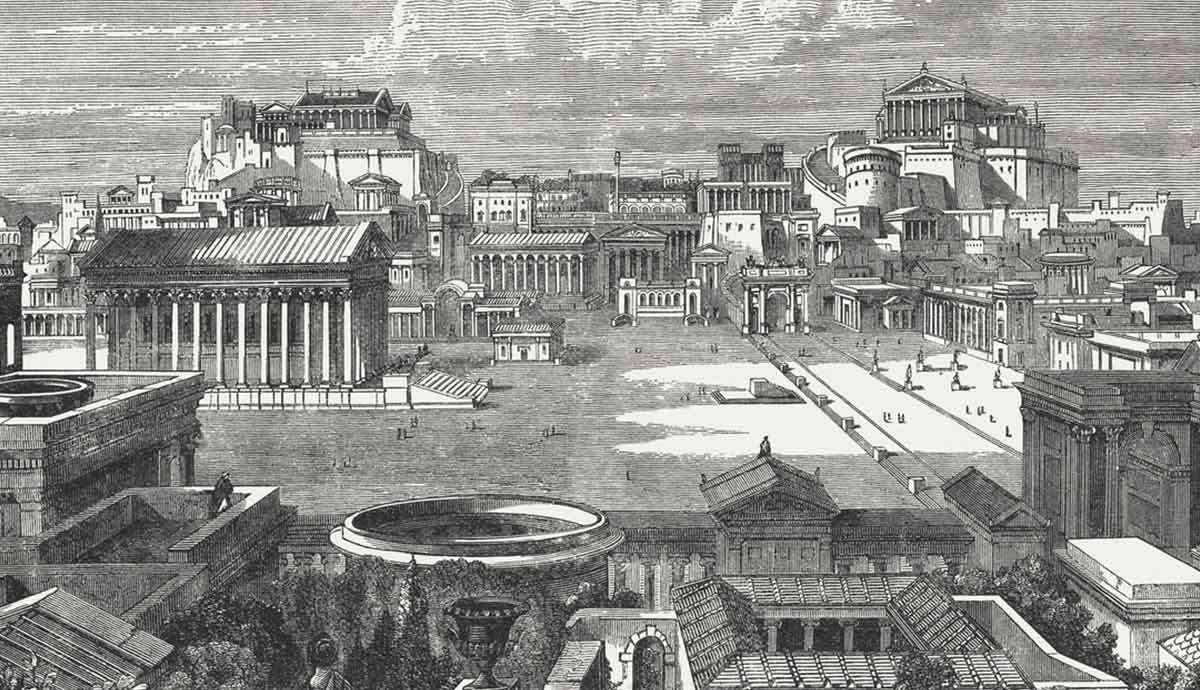

During the time of the Roman Republic, Rome was traditionally ruled by two consuls, with considerable power also lying in the hands of the senate. In 60 BCE, Rome was unofficially ruled by a triumvirate. Consulship lay in the hands of three extremely powerful men: Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, Marcus Licinius Crassus, and Julius Caesar.

The alliance would not last long, however, as political ambition and the vagaries of fortune changed the dynamic of the three consul’s relationships to each other. In 54 BCE, according to Roman historian Seneca, Caesar was in Britain when he heard the news that his daughter Julia, the wife of Pompey, had died in childbirth.

Caesar’s conquest of Gaul, and his familial ties to Pompey had helped keep the two men from plotting against each other, but with the end of the Gallic campaign and the death of Julia there was little in the way to inhibit disagreements from turning into life or death struggles between the two consuls.

A year later, Crassus was removed from the coming power struggle as he was killed at the Battle of Carrhae on the eastern edges of the Roman Republic.

With a powerful force of many legions under his command, Caesar was well positioned to use force to take control in Rome, and as his campaign came to an end the senate wrestled with how to reintegrate him into the political scene of Rome, especially since his victory had brought him incredible popularity among the populace.

From 55 BCE to 52 BCE, a breakdown in order fueled by political tension caused anarchy to reign in certain portions of the city of Rome. Pompey invested much time and effort into meeting these challenges. The casus belli for Julius Caesar, however, came when the senate elected Pompey as the sole consul, and made plans to strip Caesar of his legions.

This move was too much for Caesar, and at this point on, war was inevitable. Neither Pompey nor Caesar wanted to go to war with the other, but personal pride and the political climate propelled them toward an inescapable vortex of conflict.

The War

In January of 49 BCE, Julius Caesar and his legions invaded Italy which was poorly prepared for such an undertaking. Caesar met with easy triumph, and spoke with Pompey over what course to take next. Agreements between the two fell through and the war continued. As Caesar’s legions saw victory in the Italian Peninsula, Pompey was forced to withdraw and seek victory elsewhere.

Caesar then set out to Spain to take control of the province which had been under the consulship of Pompey. He scored several victories against the Pompeian forces there and took control of the province before returning to Rome whereupon he was named dictator, giving him significantly more power than the title of consul.

With Spain subdued, Caesar sought to put an end to Pompey by pursuing him across the Adriatic, and thus beginning the Macedonian campaign against forces controlled directly by Pompey.

Crossing the Adriatic was a risky maneuver, and a fleet under the control of Pompey’s ally Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus managed to capture many of Caesar’s transports returning to Brundisium on the eastern coast of Italy.

Caesar, as a result, was stranded on the western coast of the Adriatic with just seven legions and limited supplies. If he could not defeat Pompey there, the entire war would be lost. He was, however, later reinforced by another legion, although he was still vastly outnumbered by Pompey’s forces.

The campaign did not get off to a good start for Caesar, and he failed to secure the vital supply town of Dyrrachium from Pompey’s forces. Caesar was forced to withdraw from Thessaly, and his situation became critical.

Pompey decided to finish the war and use his superior position and advantage in numbers to deal a final crushing defeat of Caesar. He met up with reinforcements from Syria and pressed Caesar into battle.

Pharsalus

On August 9, the two armies met on the southern edge of the plains of Pharsalus in Thessaly. According to Caesar’s own account, he had a total of 22,000 men which included roughly 1,000 cavalry. Facing him, the estimates of Pompey’s forces vary through historical records, which give estimates of between 36,000 to 45,000 infantrymen, bolstered by around 7,000 cavalry, easily giving Pompey a two-to-one advantage.

The two leaders deployed their army with a river protecting their flank. For Caesar, the Enipeus River protected his left flank, while for Pompey, it protected his right. Both generals set up their cavalry facing each other on the other flank.

Pompey’s cavalry, vastly superior in number, was strengthened by virtually the entire army’s contingent of archers and slingers. This gave Pompey a massive advantage on his left flank from which he intended to weaken and roll up Caesar’s right flank. This is also where Pompey positioned himself to make sure this vital part of his strategy would go according to plan. From Caesar’s left flank to his right, his generals Mark Antony, Domitius and Faustus Cornelius Sulla (the son of Lucius Cornelius Sulla) took up their positions. Caesar took up position with Sulla on the right.

Caesar’s legions, severely outnumbered, were arranged in just three lines (sections), six men deep. When Caesar saw the size of Pompey’s army, especially the cavalry, he ordered his lines to be thinned to create a fourth line to support his cavalry which would have no chance of being outnumbered seven to one by the enemy.

Caesar was far from confident, but his troops were battle-hardened and would not break easily.

The two armies stood motionless and waited for the other to make the first move. Pompey controlled the initiative and Caesar was forced to order his army to advance first. His left flank under Mark Antony and the center under Domitius advanced in good order and engaged Pompey’s right and center.

Opposite Caesar’s right flank, Pompey’s cavalry advanced and began the attack. Caesar’s right flank began to fall back and Pompey’s mounted troops peeled off in sections and prepared to outflank Caesar’s right flank.

Their success was short-lived, as Caesar’s forth line received the order to attack Pompey’s cavalry. Their assault was furious beyond expectation, and the Pompeian cavalry, in shock from the attack, began to withdraw under pressure. The fourth line pressed their advantage and the Pompeian archers and slingers, without support from their fleeing cavalry, were cut to pieces.

After the success of the fourth line was secured, Caesar ordered the third line under the command of Sulla to advance, providing vital support to the beleaguered first and second lines who were by now tiring.

The collapse of Pompey’s left flank, however, filled his forces with despair, and the battle did not last much longer, as they began to quit the field rather than be subjected to the roll-up of their left flank under the efficient advance of Caesar’s fourth line.

Pompey quit the field and his forces fled to the security of their camp. Caesar’s legions followed and attacked the camp, forcing Pompey’s troops higher up into the mountain. Without the expectation of respite or water, they threw down their arms and surrendered.

According to Caesar’s own account, he showed mercy to these tired soldiers and pardoned them all.

After the Battle

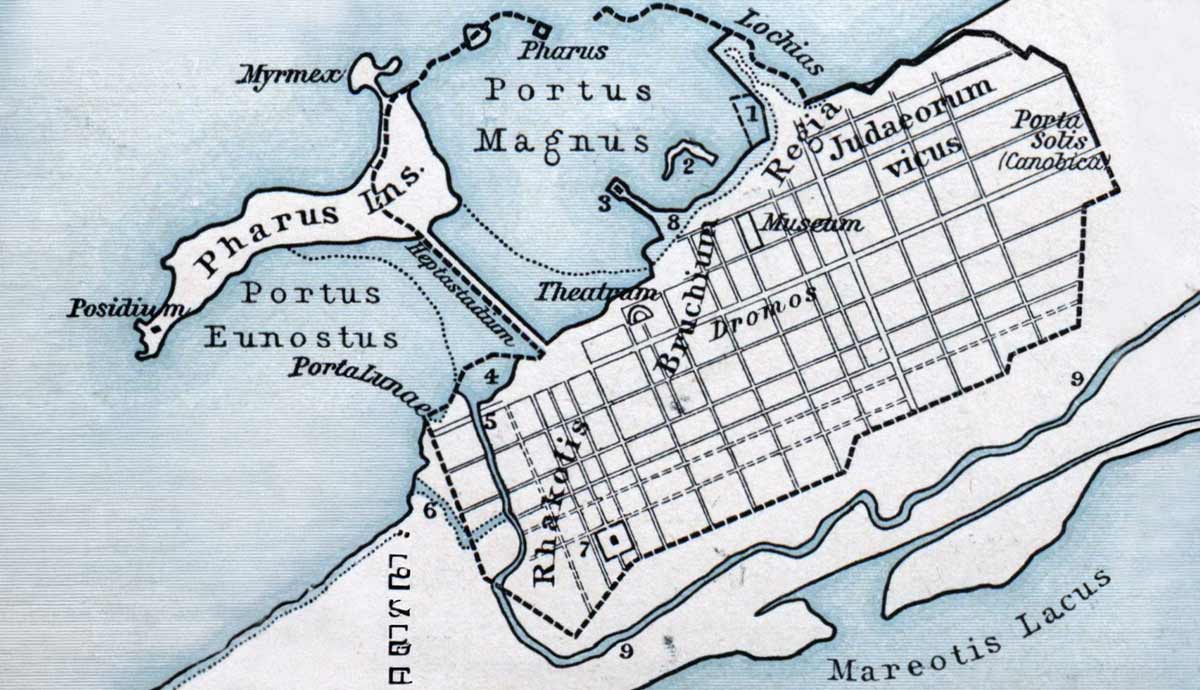

Pompey fled to the port of Larisa with a small number of men and boarded a transport. He expected to rally support on the other side of the Mediterranean, and although the war lasted for another three years, Pompey did not live to see it. He made for Pelusium on the coast of Egypt, hoping to win support from his former client, Ptolemy XIII Theos Philopator, the king of Egypt. His expectation was, however, rewarded with treachery, and he was struck down when he set foot ashore.

Although the Battle of Pharsalus did not end the war, it was a decisive victory and legitimized Caesar’s power. Until the battle, most of the Roman world had supported Pompey, but after Caesar’s victory and the assassination of Pompey, it was only a matter of time before support for the Pompeians would completely crumble.

The casualty count was completely lopsided. According to Caesar, he lost only 200 soldiers, but this number is probably closer to a thousand. Those who fought alongside Pompey, however, sustained an estimate of 6,000 to 15,000 killed, and around 24,000 captured.

Conclusion

Pharsalus was a great victory for Caesar and it served as the military foundation from which he could assert his power over the Republic. Despite this, however, August 9, 48 BCE was a sad day for Rome, as legions were set upon legions in an episode of fraternal slaughter.