At the turn of the 3rd century CE, China descended into civil war as the court of the Han Dynasty was torn apart by factionalism. As central authority melted away, ambitious warlords competed for power in the name of a puppet emperor. By the time the last Han Emperor was forced to abdicate in 220 CE, three claimants remained, marking the beginning of the Three Kingdoms Period. The Battle of Red Cliffs, fought in the winter of 208-209 CE, was a decisive moment in bringing about the tripartite division.

The Battle for China

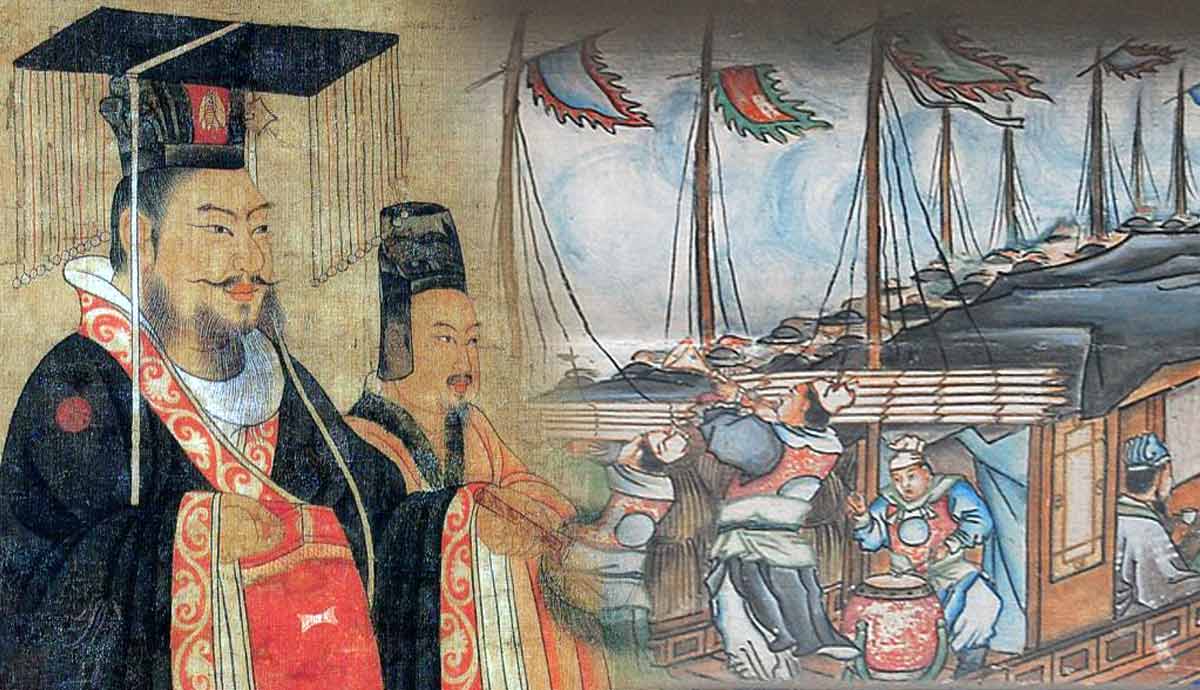

In the summer of 208 CE, a large Chinese army marched south across the Yangtze River into Jing Province (modern-day Hubei and Hunan). Their commander was Cao Cao, a statesman and general in his mid-fifties. He was recently appointed imperial chancellor and controlled northern China in the name of the young Emperor Xian of Han.

Cao Cao’s campaign was prompted by the death of Liu Biao, the governor of Jing Province. He soon secured the surrender of Liu Zong, the late governor’s second son and designated successor. Liu Biao’s elder son, Liu Qi, disputed the succession and refused to submit. Liu Qi was supported by Liu Bei, a charismatic warlord who claimed to be related to the imperial Liu clan despite his humble birth.

Liu Bei had already been forced to retreat down the Yangtze River in some disorder, though his general Guan Yu was able to take control of part of the Jing fleet and sail it downriver. The two Lius faced an uphill task with only 10,000 men each, considerably smaller than Cao’s invasion force. Their only hope was to secure an alliance with Sun Quan, the ruler of the Wu region to the east, who had been a bitter enemy of Jing Province.

Liu duly sent his advisor Zhuge Liang to Sun Quan’s headquarters at Chaisang to negotiate. As Zhuge argued that 30,000 Wu troops were enough for the allies to defeat Cao Cao’s exhausted army, Cao Cao sent an intimidating message claiming to have 800,000 men under his command. While many of his generals advised him to submit, Sun Quan’s commander Zhou Yu considered this figure greatly exaggerated and believed it possible to defeat Cao Cao.

Acting against the advice of most of his officials, Sun Quan agreed to join the anti-Cao alliance.

In late December, Zhou led 30,000 men to join Liu Bei and Liu Qi, and the allied force moved upstream to a place called Chibi or Red Cliffs, which may have been located at the confluence of the Yangtze and Han rivers in modern-day Wuhan. The ensuing battle would decide the fate of China.

Cao Cao: Master of the North

As he prepared to battle with the Sun-Liu alliance, Cao Cao was the most powerful man in China. He had been an influential court official since the 180s and had distinguished himself by leading government troops to suppress the Yellow Turban Rebellion of 184 CE. In the early 190s, he served in the coalition against Dong Zhuo, the tyrannical warlord who had taken control of the court and deposed Emperor Shao in favor of his younger brother, Emperor Xian.

By the time Dong Zhuo was assassinated by his subordinate and adoptive son Lü Bu in 192 CE, the anti-Dong coalition had already collapsed. Over the following years, Cao Cao gradually built up his power base in central China at the expense of local rivals and recruited large numbers of former Yellow Turbans to his cause.

In 196 CE, Cao became the latest in a line of warlords to take control of the young emperor and moved him to his power base at Xuchang in present-day Henan province. Under a thin veneer of imperial legitimacy, Cao Cao secured the submission of minor warlords.

In 200 CE, Cao faced an invasion by Yuan Shao, his powerful rival to the north. While Cao Cao is believed to have been outnumbered by his enemy, he defeated him at the Battle of Guandu after launching a surprise night attack against the latter’s extended supply lines. Defeat at Guandu broke Yuan Shao’s power, and his death in 202 brought about a ruinous civil war between his sons Yuan Tan and Yuan Shang, enabling Cao Cao to take control of northern China by 204.

Sun Quan: Ruler of the East

While Cao Cao was consolidating his power in northern and central China, the Sun family was in the process of conquering the Jiangdong region in eastern China south of the Yangtze River, which had once been ruled by the ancient kingdom of Wu.

The patriarch of the family, Sun Jian, had served in the anti-Dong coalition and, in early 191, led a vanguard column to occupy the imperial capital of Luoyang, which had been abandoned by Dong Zhuo. Later that year, he launched an invasion of Jing Province to the west on the instructions of his overlord Yuan Shu and was killed in an ambush.

Sun Jian’s elder son, Sun Ce, took over his father’s territories and quickly gained a reputation as an excellent military leader, subduing his local enemies and conquering the whole of the Jiangdong region in less than a decade. In 197, when Yuan Shu declared himself the emperor of the new Zhong dynasty, Sun Ce broke away and remained nominally loyal to the Han emperor.

In 200 CE, Sun Ce was assassinated at the age of 25 after a private dispute and succeeded by his 18-year-old brother Sun Quan. Although he lacked his father and brother’s military prowess, Sun Quan could count on a body of talented generals and advisors, including veterans Cheng Pu and Huang Gai of his father’s generation and younger officers, including Lu Su and Zhou Yu, his brother’s closest friend.

Liu Bei: Imperial Kinsman

Unlike his rivals, Liu Bei was a man of humble birth who grew up selling shoes and straw mats with his widowed mother. However, his claim to be descended from the Han imperial family won him a small but loyal band of followers, including Guan Yu and Zhang Fei, who joined him as he organized a militia against the Yellow Turban Rebellion in 184.

Liu Bei and his motley crew of warriors fought with distinction and were rewarded with official appointments by the Han government. In the early 190s, he joined Gongsun Zan in the far north of China, but the volatile situation saw him serve several masters. By 197, he was allied to Cao Cao and appointed to the office of General of the Left with orders to attack Yuan Shu.

Although he remained loyal to the Han dynasty, Liu Bei recognized that Cao Cao was controlling the emperor and was afraid that Cao himself would usurp the throne. In 199, he turned against Cao Cao but was defeated and forced to flee to Yuan Shao, while his subordinate Guan Yu was taken prisoner and briefly entered Cao Cao’s service.

Liu Bei served as Yuan Shao’s cavalry commander during the Guandu campaign and launched raids behind enemy lines. He was then sent to request military aid from Liu Biao in Jing Province. After Yuan’s defeat at Guandu, Liu Bei remained in Jing and garrisoned a frontier town but became an important influence at Liu Biao’s court by the time of the latter’s death in 208.

A Change of Wind

The 30,000 troops under Zhou Yu increased the anti-Cao coalition’s numbers to 50,000. Even though Cao Cao’s boast of 800,000 men is generally discredited by historians, Zhou Yu’s more realistic estimate of 250,000 still ensured Cao Cao enjoyed a significant numerical advantage, though most of his were northerners unaccustomed to amphibious warfare, and a large number of men succumbed to disease in the damp conditions.

While the main historical source for the Battle of Red Cliffs is the Records of the Three Kingdoms, written by Chen Shou at the end of the 3rd century CE, the battle is better known from the Romance of the Three Kingdoms by Luo Guanzhong in the 14th century CE near the beginning of the Ming Dynasty. The Romance offers a more dramatic account of the battle by incorporating other sources as well as myths and legends that emerged over the centuries, making it difficult to separate fact from fiction.

According to the Romance, which has a tendency to magnify the role of Liu Bei and his subordinates, the coalition strategy was devised jointly by Zhuge Liang and Zhou Yu. They planned to send fireships into the midst of Cao Cao’s fleet before taking advantage of the ensuing disorder to rout the enemy’s forces on land, with Zhou Yu leading the main assault and Liu Bei cutting off Cao’s retreat.

In an apocryphal tale from the Romance, the allied army was short on arrows, and Zhuge Liang agreed to provide Zhou Yu with 100,000 arrows within ten days or face execution. On the eve of the 10th and final day, Zhuge sailed a flotilla of boats covered in straw towards the enemy lines under cover of darkness. Cao Cao’s archers could not stop themselves from firing their arrows at the ships, and Zhuge Liang was soon able to return to base to present Zhou Yu with hundreds of thousands of arrows.

In another tale from the Romance not mentioned in the Records, as the designated date of attack dawned, Zhou Yu noticed that the wind was continuing to blow eastwards, away from the enemy. In these circumstances, any attack using fireships would not only do no damage to the enemy but threaten to destroy Zhou’s own fleet. Claiming an ability to control the weather, Zhuge Liang requested an altar to be built so he could perform the appropriate Daoist ritual, which would enable the wind to change direction after three days, just in time for the battle.

The Flaming River

Whether as a result of Zhuge’s supernatural methods or otherwise, the wind was blowing westwards when the veteran Wu general Huang Gai approached Cao Cao with a false offer of surrender. When this was accepted, Huang filled a squadron of ships with flammable material and sailed towards enemy lines.

As he approached Cao’s fleet, Huang Gai and his men set fire to the ships, jumped into the small boats they towed behind them, and rowed to safety. In order to provide his northern soldiers with a more stable fighting platform, Cao Cao ordered his ships to be chained together. With the wind carrying the fireships towards them, Cao Cao’s men struggled to untangle the ships, and the whole fleet was soon in flames.

Taking advantage of the disorder in Cao’s ranks, Zhou Yu launched his main assault on land and shattered the northern army. Cao Cao’s disorderly men were bogged down as they retreated along the muddy Huarong Road.

In a famous episode from the Romance of the Three Kingdoms, Guan Yu had set up an ambush to block the Huarong Road but was persuaded to let the chancellor escape as a mark of gratitude for the generosity Cao Cao had shown him while he was in his captivity a decade earlier. In reality, Liu Bei did not launch a determined pursuit, and Cao Cao was relieved that his retreat remained open.

Three Kingdoms

Defeat at Red Cliffs left Cao Cao with only a foothold in Jing Province at Jiangling, which he entrusted to his cousin Cao Ren. While Zhou Yu advanced to fight Cao Ren, Liu Bei took the opportunity to seize the southern half of Jing Province. In 213-214, Liu Bei used Jing Province as a base to conquer Yi Province to the west (modern-day Sichuan and Chongqing), also known by its ancient name of Shu. Since Liu Bei claimed the legacy of the Han dynasty, the state that he ruled from his capital of Chengdu came to be known as Shu Han.

Although the Sun-Liu alliance was strengthened by the marriage of Liu Bei to one of Sun Quan’s sisters in 209, tensions ran high over the possession of Jing Province. When Liu Bei set out on his conquest of Yi Province, Lady Sun returned to her brother’s court. In 219 CE, while Guan Yu was attacking Cao Cao’s forces at Fancheng, Sun Quan’s general Lü Meng invaded Jing Province, capturing and executing Guan Yu in the process.

While Cao Cao and Sun Quan continued to skirmish in eastern China, Cao Cao focused most of his energies in the west, incorporating Liang province and securing the submission of Zhang Lu, the ruler of Hanzhong, which was lost to Liu Bei in 219.

While Cao Cao remained the power behind the throne, he refused to usurp Emperor Xian’s throne, settling for the title of King of Wei in 216 CE. Following his conquest of Hanzhong, Liu Bei declared himself King of Hanzhong in 219. Sun Quan, who had submitted to Cao Cao in 217, proclaimed himself King of Wu in 221 and reasserted his independence the following year.

Cao Cao’s death in 220 CE saw the formal end of the Han empire, as his son Cao Pi proclaimed himself Emperor Wen of the (Northern) Wei dynasty. Liu Bei assumed the imperial dignity in 221 as Emperor of Shu Han, ruling from Chengdu. Sun Quan made himself Emperor of (Eastern) Wu in 229, with his capital in the city of Jianye, modern-day Nanjing.

These three self-proclaimed empires continued to fight for dominance over China for the next half-century. Although Northern Wei gradually triumphed over its rivals and conquered Shu in 263, the Cao family was soon overthrown by the influential Sima family, who founded the Jin Dynasty in 266 CE and extinguished the remnants of Eastern Wu in 280.