summary

- Bayard Rustin was a key organizer in the Civil Rights Movement who advocated for nonviolent tactics.

- Gay Rights Activist: Rustin was openly gay and had ties to the Communist Party, which led to him being less recognized than other civil rights leaders.

- Rustin & Malcolm X: In 1962, Rustin debated Malcolm X on the topic of integration versus separation of the Black community.

- March on Washington: Rustin met Martin Luther King Jr. during the Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1954. He became Martin Luther King’s advisor and helped organize the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

- Bayard Rustin’s Later Years & Legacy: After the March on Washington, Rustin continued to advocate for racial equality and economic justice. He died on August 24, 1987, and received the Posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom Award for Activism in 2013.

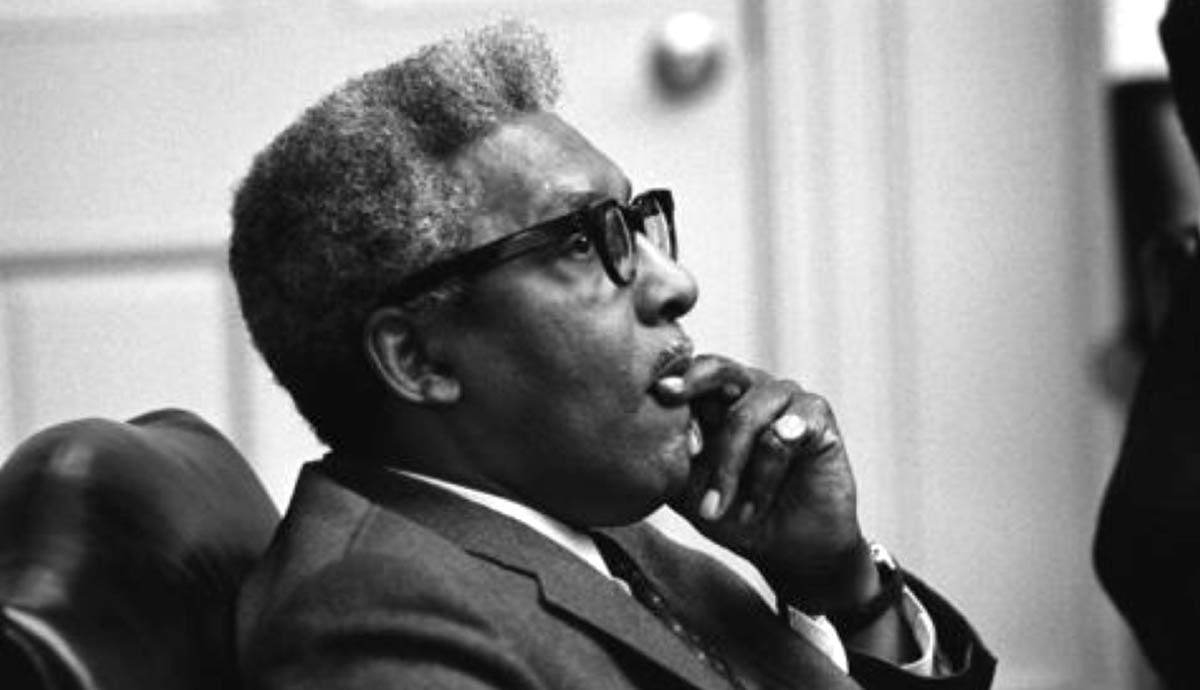

Bayard Rustin was a civil rights activist who advised Martin Luther King Jr. as the Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court ruling sparked the beginning of the long battle of the Civil Rights Movement. He was deputy director for the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Bayard Rustin became a leading figure in the Civil Rights Movement through his teachings of nonviolent civil rights tactics. He was also a prominent member of several civil rights organizations.

Early Life of Bayard Rustin

Bayard Rustin grew up in West Chester, Pennsylvania, where he was raised by his grandparents, who were Quakers. His religious faith influenced his beliefs in nonviolent practices in the Civil Rights Movement and his strong opposition to the war.

During his childhood, Rustin had the opportunity to meet with civil rights activists, such as W.E.B. Du Bois, because his grandmother was a member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

After high school, Rustin attended Wilberforce University on a music scholarship, as he was an excellent singer. However, after organizing a protest against the poor-quality cafeteria food, he lost his scholarship and left the university in 1932. Rustin then continued his studies at Cheyney State Teachers College before moving to Harlem, where he attended the City College of New York in 1937.

While attending City College, Rustin joined the Young Communist League (YCL) since the Communist Party supported the emerging Civil Rights Movement. Shortly after World War II broke out, communists shifted their attention toward the war, leading to Rustin ending his commitment to the YCL. Despite Rustin pulling out of the organization, his involvement with the Communist Party would continue to be frowned upon by others throughout his career.

Another reason others did not highly favor Rustin as a civil rights leader was his homosexuality. He was openly gay in a time period that heavily discriminated against individuals who were homosexual. His homosexuality and participation in a communist organization are often attributed as the reasons why Bayard Rustin is not discussed as much as other prominent civil rights figures. However, Rustin is still recognized as a major influence on the Civil Rights Movement due to his nonviolent approach.

Bayard Rustin’s Involvement in the Civil Rights Movement

In the 1940s, Rustin joined a number of civil and human rights organizations, such as the Fellowship Reconciliation (FOR) and the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). Rustin was a key organizer for various campaigns and workshops for the organizations. A few years later, in 1953, Rustin was asked to resign from his position as race relations director of FOR due to being caught performing sexual acts with another male in Los Angeles, as it was illegal to do so at the time. However, this did not stop Rustin from continuing to expand his career as an exceptional organizer for civil rights programs and organizations.

In 1941, Rustin and civil rights activist A. Philip Randolph planned to organize a March on Washington to protest segregation within the armed forces. Randolph, however, canceled the march after President Franklin D. Roosevelt implemented the Fair Employment Act, which outlawed discrimination in the military.

In the following years, Rustin sought to expand his knowledge of nonviolence philosophies. In 1948, he took a trip to India to study Gandhi’s philosophy of nonviolence for seven weeks. He also spent time working with independence movements in Africa.

Different Perspectives: Bayard Rustin vs. Malcolm X

The values and beliefs of Bayard Rustin varied greatly from those of Malcolm X. Malcolm had more radical views and did not agree with Rustin that peaceful protest would be an effective tactic for gaining civil rights. Rustin believed that the people of America needed to work together in order to succeed. He called for the integration of Blacks and whites to accomplish social justice goals, while Malcolm X wanted separation as opposed to segregation.

On January 23, 1962, at the Community Church in Manhattan, the two had a chance to voice their different perspectives in a debate. Malcolm X explained that the new Black man did not want integration or segregation but separation. His view was that Black and white communities should operate in their own world and have control over their own society, economy, and politics.

Rustin made a moving argument in the debate, stating:

“As we follow this form of mass action and strategic nonviolence, we will not only put pressure on the government, but we will put pressure on other groups, which ought by their nature, to be alive with us and they will have to stand up and be counter in their own interest.”

There were supporters for both sides. The Black community was rightfully angry towards whites and the government for mistreating African Americans since the time of slavery. Some wanted to peacefully fight for justice, while others agreed that taking more radical and violent actions was necessary to achieve the goals of the civil rights agenda.

Bayard Rustin Becomes Martin Luther King’s Right-Hand Man

Rustin and Martin Luther King Jr. met in Montgomery, Alabama, during the bus boycott of 1954, a protest organized after Rosa Parks’ refusal to give her seat to a white passenger.

Prior to meeting Rustin, King was not very familiar with nonviolent civil rights strategies. Rustin encouraged King to resort to nonviolent practices to fuel his civil rights campaigns. While serving as MLK’s advisor, Rustin helped King write speeches and worked as his campaign organizer and nonviolence strategist.

In 1956, Rustin suggested the establishment of the nonsectarian agency Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to King, and the two became co-founders of the organization along with others. Rustin also organized the Prayer Pilgrimage for Freedom and Youth Marches for Integrated Schools alongside Randolph.

Rustin drafted several memos for King. He gave King an outline of events for the March on Washington and advised what topics King should discuss in his speech at the event. Rustin also drafted King’s memoir Strive Toward Freedom, an account of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Rustin educated King on the importance of nonviolence, and in return, King valued Rustin’s knowledge and beliefs. The two made an unstoppably great team that hurled their civil rights agenda to the forefront of the movement.

The 1963 March On Washington For Jobs & Freedom

Bayard Rustin was appointed deputy director of the 1963 March on Washington. He was in charge of organizing the march in just two months. Rustin had 200 volunteers who helped him put it together and two offices in Harlem, New York, and Washington DC. The Lincoln Memorial Program outlined the events for the demonstration.

The March on Washington, which took place on August 28, 1963, is recognized as one of the largest peaceful protests in US history. A number of organizations, such as the NAACP and the National Urban League, sponsored the march. During the event, prominent civil rights figures, including A. Philip Randolph, John Lewis, and Roy Wilkins, made several remarks. Malcolm X was also in attendance despite his disagreements with peaceful protesting.

Some of the goals of the march included the integration of public schools, voter rights protection, and a federal works program. Over 200,000 people attended the demonstration, and people became inspired by the famous “I Have a Dream” speech made by Martin Luther King. The protest was successful in some of its goals, as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 were the direct outcomes of the event.

After the March

Despite its success, Rustin felt there was still much work to be done after the march. African Americans were still suffering economically. Although the Second World War helped reduce unemployment rates, Rustin wanted to see the gap in racial and economic disparities close. In 1966, Rustin and Randolph attempted to develop the “Freedom Budget,” which would have guaranteed work for those willing and able to work. The budget was designed to benefit all people, but it was never passed.

For the next decade after the march, Rustin continued to advocate for racial equality and fight for economic justice. He moved into a Manhattan apartment in 1962. He also became involved in the gay rights movement.

Rustin met Walter Naegle 15 years later while strolling through New York City. Bayard and Walter immediately hit it off, started dating, and later lived together. In 1987, Rustin suffered from a ruptured appendix and was taken to the hospital. He went into cardiac arrest during his operation, which led to his death on August 24, 1987.

Commemoration of Bayard Rustin

Although Bayard Rustin’s story is not discussed as commonly as other prominent civil rights leaders, he is still recognized for his work in the Civil Rights Movement.

Rustin has been commemorated for his work through several posthumous awards and honors. In 2013, he was awarded the Posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom Award for Activism and the United States Department of Labor Hall of Honor Recipient.

The following year, he was an honoree in the San Francisco Rainbow Honor Walk. In 2019, Rustin was inducted into the National LGBTQ Wall of Honor at the Stonewall National Monument. In 2020, California Governor Gavin Newsom pardoned him for his 1953 conviction.

Bayard Rustin worked behind the scenes of the Civil Rights Movement by using his knowledge of nonviolent philosophies. He was an intellectual individual with tremendous ideas and organizational skills. His passion for civil and human rights helped fuel key protests, campaigns, and organizations that pushed the civil rights agenda forward. Many viewed Rustin as an outsider during his time due to his early involvement with the Communist Party and homosexuality. Despite others’ judgments, Bayard Rustin continued to focus on what mattered the most: justice, peace, and equality for all. This led him to become one of the most quietly influential civil rights leaders in history.