Film Noir got its name from the French word for dark or black film. The name was given to distinctively bleak and fatalistic U.S. crime movies of the 1940s and 1950s. So distinctive in fact that you can tell in the first five minutes that you’re seeing one. It’s black-and-white, naturally, and the setting is almost always a city at night which features a lone man on the verge of falling into a maelstrom of crime, transgression, and violence.

Film Noir Basics

Who is this protagonist, this fated outsider? You may see his story told in flashbacks, past events cued by his (or another character’s) voice-over narration. Last, but certainly not least, there is a woman. Invariably that femme is fatale to the hero.

Now, all Noirs don’t fit this crooked groove, there are plot variations, but this one is archetypal. So archetypal that it has been replicated in many modern neo-noir movies like Body Heat (1984) with Kathleen Turner playing femme fatale to William Hurt as her gullible, libidinal prey. Such powerful and sexualized women have long caught the eye of feminist film academics, for noir is a rarity in old Hollywood in that it starkly portrayed women as independent agents who live outside the law (both legal and patriarchal) and use their sexuality as a devious means to an end. That they usually are punished for such behavior is also well-known, but then again nearly all illicit actions by either sex were punished in moralizing, heavily censored classic Hollywood.

The christening of Film Noir came late, not from Hollywood itself, but from the French critics who first noticed a unique wave of dark, downbeat, stylistically remarkable crime movies landing in Europe in the years after World War II. A look back at cultural history tells us that noir didn’t magically fade in during the 1940s, but rather has a tangled web of roots. There was the popular 1930s gangster film, of course. Add in the American hard-boiled crime and detective fiction of Raymond Chandler, James M. Cain, and Dashiell Hammett.

Further back, there’s the 1920s German Expressionism, highly influential not only for its shadowy and nightmarish imagery but for portrayals of male protagonists victimized by dark forces that were out of their control. It’s no accident that several of the best U.S. noirs were directed (and photographed) by German or East European émigrés who moved to the West with the rise of Hitler. They not only brought with them their filmmaking talents, but a skeptical, sardonic outlook, quite contrary to the typical Shirley Temple utopian and escapist mindset of late-1930s Hollywood.

Lastly, somewhat intangibly, there was World War II itself. The USA in 1946 was a far different place than it had been in 1940—socially, economically, politically, militarily, but also psychologically. Sure, Americans had suffered through the Depression, scarring many millions, but the war was something else entirely. Of the 16 million men and women who served, there were over a million casualties, including 400,000 or more dead. Those on the front lines who made it back had experienced the horrors and atrocities of war unprecedented in history, from Pearl Harbor to Iwo Jima and Hiroshima, from D-Day and Anzio to the “liberation” of the Nazi concentration camps.

For most returning G.I.s—and most Americans—Hollywood entertainment could stand a shot of realism, if not cynicism. Still, while the country had emerged triumphant and relatively unscathed compared to its European allies, its economy and military second to none, there were dark clouds on the horizon. An obscure US senator named McCarthy would launch his now-notorious communist witch-hunt, unleashing a decade or more of paranoid blacklisting from coast to coast, paralleled by front-page investigations by a House committee into similar Un-American activities. Those digging deeper into the contextual complexities of Noir may see such paranoia lurking in the shadows—with its counterparts, betrayal and the double-cross—as well as glaringly persistent themes that dramatically contrast the sunny, domesticated good girl against the sexy bad girl with neither home nor husband, but likely a gun.

Just how dark does classic Noir get? Whether robbing an armored car, bumping off a dimwit husband for the insurance money, or melting Malibu with a white-hot nuke, noir takes a walk on the wild side of the street, one lit up by lurid neon, glowing cigarettes, and smoldering passions. Here are 11 Film Noirs you should know.

11. Double Indemnity

Double Indemnity (1944) was directed by Billy Wilder. The first great Noir in all its premium-grade glory, with Barbara Stanwyck as the twisted temptress who hooks up with a rogue Los Angeles insurance salesman, played by Fred MacMurray, to knock off her husband for the insurance money. As doubly superb as the leads are, keep your eyes and ears open for Edward G. Robinson, memorable as MacMurray’s whip-smart actuarial colleague and forsaken father figure. Peppered with double entendres, Wilder’s script (co-written with Raymond Chandler from the James Cain novel) shrewdly eluded the censorship police.

10. Mildred Pierce

Mildred Pierce (1945) was directed by Michael Curtiz. There are few Noirs with women as the fallen victim, but Hollywood diva Joan Crawford made an Oscar-winning comeback as the titular Mildred, an L.A. housewife who dumps her shiftless husband and cooks up a rich solo career as a restaurateur. This second Cain adaptation nevertheless has its dark corners with Ann Blyth as Veda, Mildred’s poisonously spoiled daughter from hell.

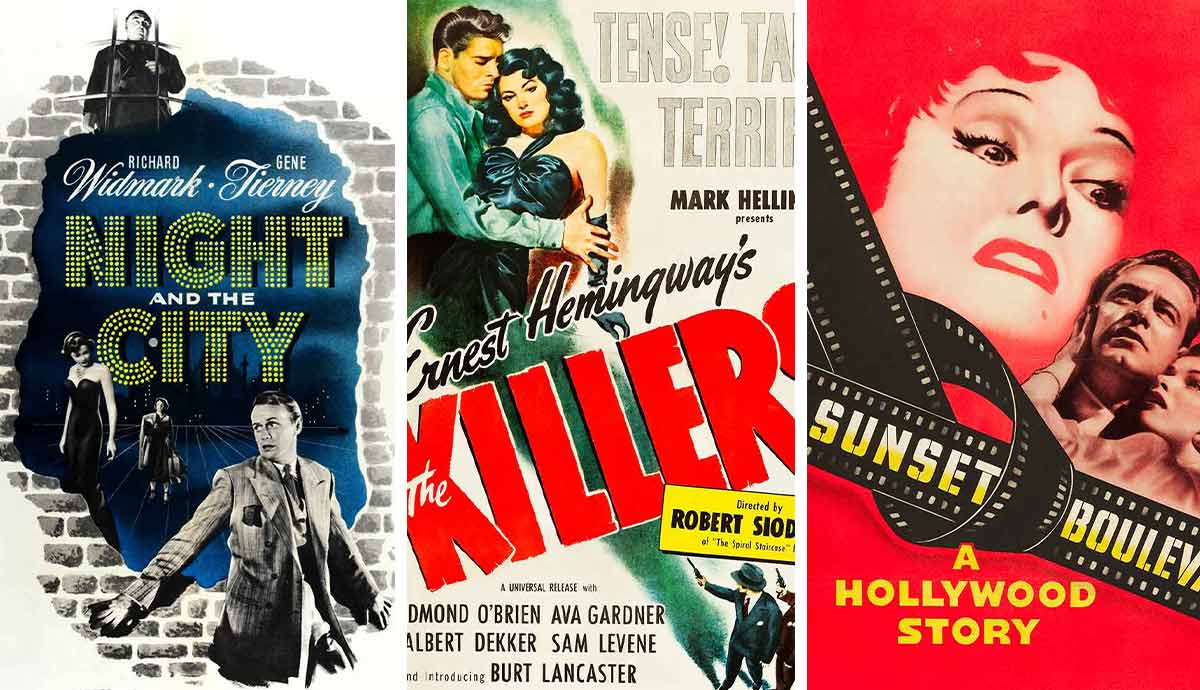

9. The Killers

The Killers (1946) was directed by Robert Siodmak. Once the war was over, Noir runneth over, frequently foregrounding men with inconstant spouses—suspiciously inscribed by true-life stories of veterans returning to women who were either changed or gone. In an Ernest Hemingway short story, Burt Lancaster made his Hollywood debut as the Swede, a boxer whose downfall is retold in flashbacks instigated by an insurance investigator. The Killers also spotlights the arresting breakthrough of Ava Gardner as the singing, sultry—and possibly lethal—Kitty.

8. Out of the Past

Out of the Past (1947) was directed by Jacques Tourneur. For all of Humphrey Bogart’s reputation as the exemplar private-eye hero, it was the slouching, sleepy-eyed Robert Mitchum who perfectly fit the fateful gumshoes made-to-order for these stories. Here he’s hired to track down the runaway moll (Jane Greer) of a mobster (an early Kirk Douglas role). Nicholas Musuraca’s low-key chiaroscuro cinematography is outstanding, complementing Tourneur’s mise-en-scene (the expressive combination of the décor and settings) foreshadowing Mitchum’s tangled fate.

7. The Lady from Shanghai

The Lady from Shanghai (1948) was directed by Orson Welles. The story goes that when the Columbia studio czar Harry Cohn saw that his glamorous pinup star Rita Hayworth had her hair cut and dyed platinum blond for this picture, Cohn shelved it for two years. Like too many other Welles’ films, Shanghai was brutally cut by the studio, accounting for its choppy quality. Nevertheless, it stands as a fractured masterwork, the tall tale of an Irish seaman (Welles) who’s reeled into a fishy seaboard scheme hatched by a crippled tycoon (Everett Sloane), his creepy partner (Glenn Anders) and a Ulysses-class siren (Hayworth).

6. The Third Man

It was likely the eminent British director Carol Reed had help translating Graham Greene’s post-war thriller to the screen—and from none other than Orson Welles, filling out his cameo role as illusive black marketer Harry Lime. In Allied-controlled Vienna, Lime is discovered (or vice versa) by his old friend (Joseph Cotten), who must be convinced by an upright British officer (Trevor Howard) that Harry is not just an ugly American, but one with blood on his hands. Reed’s climactic chase through the Vienna sewers is one of noir’s iconic set pieces, while Anton Karas’ distinctive zither music was heard echoing worldwide throughout the 1950s.

5. Sunset Boulevard

Sunset Boulevard (1950) was directed by Billy Wilder. I am big, it’s the pictures that got small! insists the reclusive silent-film star Norma Desmond (Gloria Swanson) in Wilder’s second pantheon noir. Opening with an ingenious flashback narrated by Norma’s broke-screenwriter-turned-gigolo (William Holden), this Boulevard of broken dreams immortalized Miss Desmond in not just her signature closing close-up, but in the hit Andrew Lloyd Webber musical that dawned 40 years later starring Glenn Close.

4. Gun Crazy

Gun Crazy (1950) was directed by Joseph H. Lewis in 1950. This was a watershed year for stellar noirs, including this low-budget independent film that shines with some of postwar Hollywood’s most inventive location cinematography. In a bang-up performance as a side-show Annie Oakley, U.K. actress Peggy Cummins meets her match when she meets John Dall, and together they move like Bonnie and Clyde across a wild West. Hollywood censors forced Lewis to tack on scenes of the duo’s contrition, so artificial you wonder if he was intentionally shooting to miss.

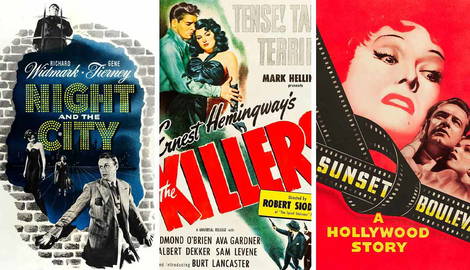

3. Night and the City

Night and the City (1950) was directed by Jules Dassin. The movie follows Harry Fabian (Richard Widmark), a two-bit hustler and shill plying his trade in a nocturnal noir nether world of London. A refugee from the darkening Hollywood blacklist, Dassin was never more cinematic—nor more socially resonant—than in his study of Harry’s grimy, all-consuming, be-bopping climb to the top of the underworld wrestling racket. Played with hepped-up panache by Widmark, Harry crosses everyone, even the woman and the divine Gene Tierney.

2. Kiss Me Deadly

Kiss Me Deadly (1955), directed by Robert Aldrich. Remember me—that’s what a half-crazed hitchhiker (Cloris Leachman) enigmatically says to L.A. shamus Mike Hammer (Ralph Meeker) in Aldrich’s unforgettable version of the 1953 Mickey Spillane pulp fiction. While the sadistic, hand-crushing Hammer is the nominal hero, he’s dinged at every blind turn, notably by the women witnessing his alpha-male march to find the Great Whatsit.

1. Touch of Evil

First signed only to act in this gnarly late noir, Orson Welles got the directorial job at the behest of (then politically liberal) Hollywood demigod Charlton Heston. In a mustachioed stretch, Heston plays a Mexican government honcho who strolls into a sketchy U.S. border town with his Anglo wife (Janet Leigh) and gets into a confrontation with the town’s reptilian sheriff (Welles). The film is punctuated with more than a few touches of cinematic brilliance like the famed opening long take to Henry Mancini’s jazzy intro.