By the late 1960s, hostilities between the majority Protestant-unionist government of Northern Ireland and the minority Catholic-nationalist population were on the rise. The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association campaigned to end discrimination against the Irish (mainly Catholic) minority in the British province. The Northern Irish government of the day requested the help of the British military to quell the hostilities, but the British Army did anything but. The fateful events of Bloody Sunday in Ireland defined British-Irish relations for more than a generation.

Tensions in Northern Ireland Prior to Bloody Sunday

By the late 1960s, the Northern Irish city of Derry (officially Londonderry) had become the focal point of a civil rights movement spearheaded by groups such as the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA). In August 1969, a riot called the Battle of Bogside led the Northern Ireland political administration to request British military support. Initially, the British Army was welcomed compared to the alternative, Northern Ireland’s Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC), the Northern Irish police force, because the RUC was viewed as a sectarian (anti-Catholic) police force.

As levels of violence increased in Northern Ireland at the start of the 1970s, internment without trial was introduced on August 9, 1971. Codenamed Operation Demetrius, the Northern Irish government requested an operation to enforce internment without trial en masse, and the British government approved this request. Over the night of August 9-10, armed soldiers carried out dawn raids across Northern Ireland, seeking people suspected of involvement in the Irish Republican Army (IRA). Three hundred forty-two people were arrested on the first night and imprisoned without trial. Everyone arrested was an Irish nationalist or republican, and most were Catholics.

The intelligence used to determine who was arrested was faulty and outdated. Many who were arrested were no longer militant republicans or members of the IRA; several never had been. This heavy-handed approach led to four days of violence that led to the deaths of 20 civilians, two IRA members, and two British soldiers. Within 48 hours, over 100 of those arrested had been released.

Increased Violence in Northern Ireland

Levels of violence rose across Northern Ireland with the commencement of internment without trial. After August 1971, 30 British soldiers were killed, compared to just ten that year prior to the introduction of internment without trial. By the end of 1971, six British soldiers were killed in the city of Derry alone. More than 1,300 rounds were fired at the British military forces, and 180 nail bombs were discovered. The British Army had responded by firing 364 rounds in return. Additionally, nearly 30 barricades were established in Free Derry, a self-declared autonomous Irish nationalist part of Derry. The British Army’s one-ton armored tanks could not even pass through 16 of these barricades.

Just 12 days before Bloody Sunday in Northern Ireland, on January 18, 1972, the Northern Irish prime minister, Brian Faulkner, prohibited all demonstrations and marches in the region for the rest of the year. Four days after the ban was instated, an anti-internment protest march was held near Derry. Several thousand people joined the protest. The British Army’s Parachute Regiment prevented the protestors from reaching their destination, an internment camp. Some of the protestors threw stones at the British military unit and tried to evade the barbed wire that had been set up. The British responded by firing rubber bullets and using tear gas against the protestors. Spectators claimed that the soldiers badly beat a number of the protestors and that the officers of some of the paratroopers had to restrain them.

On January 24, the Chief Superintendent of the Royal Ulster Constabulary informed the Commander of Britain’s 8th Infantry Brigade, Pat MacLellan, that NICRA intended to hold another non-violent demonstration march against the unpopular policy of internment without trial on January 30. The Chief Superintendent requested that the march be allowed to occur in the absence of a military presence. MacLellan agreed to propose this approach to General Robert Ford, the Commander of Britain’s Land Forces in Northern Ireland. The next day, Ford placed Pat MacLellan in overall command of the operation to contain the January 30 march.

On Thursday, January 27, two RUC officers were shot dead in their patrol car in Derry. In response, the Democratic Unionist Party, a British unionist political party that had been founded by Ian Paisley just four months earlier, announced its intention to hold a public religious rally in the same place where the two RUC officers had been killed in their patrol car. On Friday, NICRA declared that it wanted “special emphasis on the necessity for a peaceful incident-free day” (Conflict Archive on the Internet, 2001a) at its march on January 30.

January 30, 1972: Bloody Sunday in Northern Ireland

On the morning of Bloody Sunday, British paratroopers entered Derry to assume their positions. Operational Brigadier Pat MacLellan issued orders to the commander of the 1st Battalion Parachute Regiment (1 Para), Lieutenant Colonel Derek Wilford. (Wilford had only been put in charge of the proposed arrest operation on January 25 by General Ford.) Wilford then delivered orders to Major Ted Loden, the commander of the 1 Para company that would launch the arrest operation.

The planned march was due to start at Bishop’s Field in the Creggan housing estate and continue to the Guildhall in the city center, where the day would end in a peaceful rally. (The Creggan housing estate is not far from the Creggan Road, where the two RUC officers were shot and killed.) Ten to fifteen thousand people set off at 2:45 p.m.

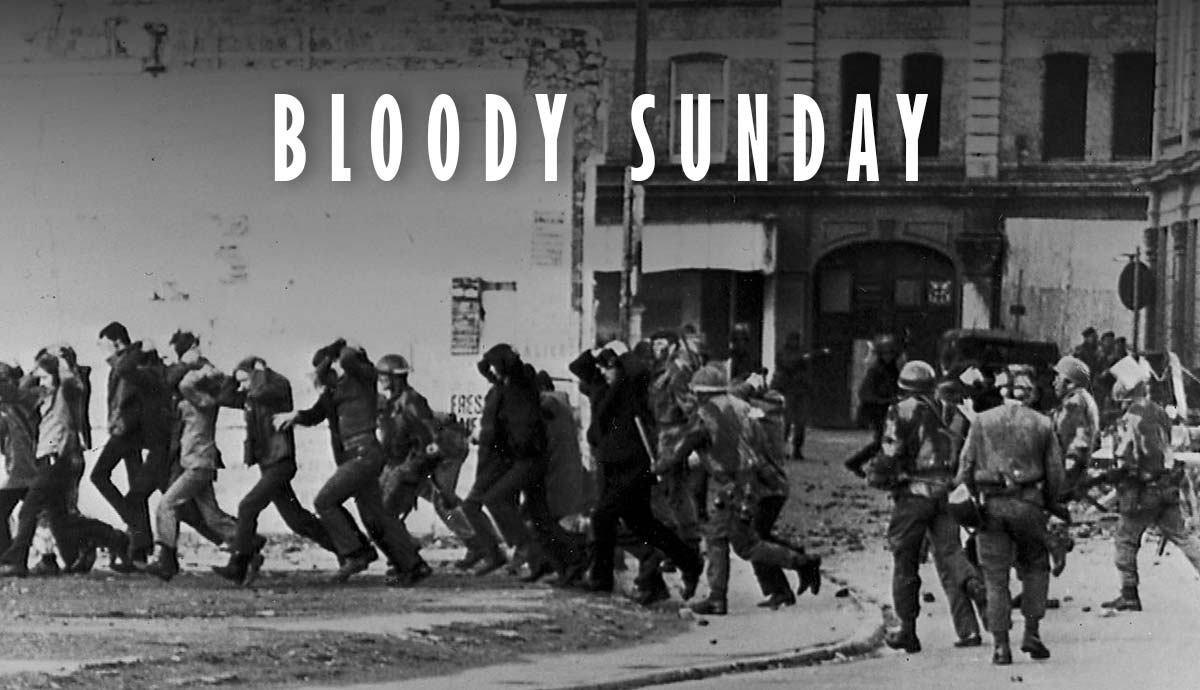

The march made its way down William Street, but when it approached the city center, the protestors found their way blocked by the British Army. At approximately 3:45 p.m., the organizers told the protestors to change the direction of the march to go down Rossville Street, intending to hold the rally at Free Derry Corner instead. Most of the marchers followed the organizers’ instructions. At this point, some protestors broke away from the march and started throwing stones at the soldiers handling the barriers. The soldiers fired rubber bullets, tear gas, and water cannons at the breakaway contingent. At this stage, witnesses reported that the discord was not any more violent than usual.

When Peaceful Protest Turned to Violence

Some of the breakaway protestors noticed British soldiers located in an abandoned three-story building overlooking William Street and began throwing stones at them. At about 3:55 p.m., the paratroopers started firing at the protestors. A 15-year-old and a 59-year-old were shot and wounded (the 59-year-old died five months later). The paratroopers received the command at 4:07 p.m. to move into William Street and start an arrest operation to detain any remaining rioters. The 1st Battalion Parachute Regiment, both on foot and in armored vehicles, was hot on the heels of people running down Rossville Street and into the Bogside, trying to escape.

Brigadier MacLellan had ordered that just one company of paratroopers break through the barriers on foot and that the civilians were not to be pursued down the street. Lieutenant Colonel Wilford disobeyed this order, which meant that it became too difficult to tell who was a rioter and who was a peaceful marcher. Many witnesses later recounted that the soldiers verbally abused the civilians, threatened to kill them, battered them with the butts of their rifles, and fired rubber bullets at them. The vehicles hit two of these civilians.

One group of paratroopers, the Support Company of 1 Para, positioned themselves about 80 meters from a rubble barricade that crossed Rossville Street. Some of the rioters began throwing rocks at the soldiers, but they were not close enough to the military men to inflict any damage. Nevertheless, the paratroopers opened fire on the rioters, killing six and wounding one.

One sizable group of agitators tried to escape but found themselves in the car park of the Rossville Flats estate, which was enclosed on three sides by residential tower blocks. The paratroopers opened fire on the rioters who struggled to flee, killing one and wounding six. The man who was killed had been running alongside a priest.

Another group of breakaway protestors fled to the car park of Glenfada Flats. This car park was also surrounded by three tall apartment buildings on three sides. The paratroopers shot people from across the car park at a distance of some 35 to 45 meters. Two civilians were killed by these shots, and at least another four were wounded. The soldiers kept running through the car park and passed through to the other side of the buildings. The paratroopers who passed through the southwest corner killed two more civilians. Other soldiers had left Glenfada Flats via the southeast corner, and these paratroopers shot another four rioters, killing two.

In total, it was only about ten minutes from when the paratroopers drove into the Bogside until the last of the rioters were killed. More than a hundred rounds were fired by the soldiers, who didn’t issue a warning before they opened fire. In total, of the 26 civilians who were shot, 13 died that day, and one died more than four months later. The family of the man who died later believed that his death was a result of injuries inflicted on Bloody Sunday in Ireland.

The massacre occurred in four main areas: the rubble barricade across Rossville Street, the car park of Rossville Flats, the south side of Rossville Flats, and the car park of Glenfada Flats.

The Immediate Aftermath of Bloody Sunday

Other than the paratroopers, all eyewitnesses, including marchers, local residents, and both British and Irish journalists, stated that the paratroopers fired into an unarmed crowd, at people who were running away, or people who were trying to help the wounded. None of the British soldiers were injured. No spent bullets or nail bombs were ever recovered to support the paratroopers’ claims that they had been attacked. However, the British Army’s official account was described in the House of Commons in London by the British Home Secretary the following day.

He said, “The Army returned the fire directed at them with aimed shots and inflicted a number of casualties on those who were attacking them with firearms and with bombs.” (Conflict Archive on the Internet, 2001b). The Home Secretary also told the Commons that an official inquiry would be held into the day’s events.

On February 2, 1972, the funerals of eleven of the dead were held. Tens of thousands of mourners attended. The Republic of Ireland held a national day of mourning, while a general strike was held the same day. The strike was the largest that Europe had seen since the Second World War in relation to the size of Ireland’s population. Catholic and Protestant churches held memorial services in addition to synagogues across Ireland. In Dublin, between 30,000 and 100,000 marched to the British Embassy carrying 13 coffins and black flags. A crowd later attacked the embassy, burning the Chancery down to the ground.

The Widgery Inquiry

Two inquiries were held into Bloody Sunday in Ireland, the first in 1972. The British prime minister appointed the Lord Chief Justice of England, Lord Widgery, to lead the inquiry. His report was finished in just ten weeks and published a week later.

Widgery’s report stated that “None of the deceased or wounded is proved to have been shot whilst handling a firearm or bomb. Some are wholly acquitted of complicity in such action; but there is a strong suspicion that some others had been firing weapons or handling bombs in the course of the afternoon and that yet others had been closely supporting them” (Conflict Archive on the Internet, 2001c).

Widgery then concluded, “There would have been no deaths […] if those who organised the illegal march had not thereby created a highly dangerous situation” (Conflict Archive on the Internet, 2001c).

The tribunal saw evidence of the supposed crimes of the breakaway protestors, although tests for traces of explosives on the bodies of eleven of the deceased showed negative results. Widgery’s inquiry also determined that the paratroopers had not sought to “flush out any IRA gunmen” or punish the Bogside residents. The Widgery Inquiry’s report was called a whitewash by many who had seen the day’s events for themselves.

The Saville Inquiry

In 1998, while talks were being held over the Northern Ireland peace process, British Prime Minister Tony Blair agreed to hold a public inquiry into Bloody Sunday. Lord Saville, then a Lord Justice of Appeal, headed the inquiry, which featured other judges from Canada, Australia, and New Zealand. This inquiry listened to testimony continuously from March 2000 to November 2004. The inquiry interviewed local residents, soldiers, journalists, and politicians while also reviewing photographs and video footage. In 2007, one general (who was a captain in 1972) backtracked on what he had been saying for decades and stated that he had no doubt that innocent people had been killed.

One former paratrooper testified in 2000 that the night before Bloody Sunday, his platoon leader had said, “Let’s teach these buggers a lesson. We want some kills tomorrow.” He further explained, “Several of the blokes had fired their own personal supply of dum-dums. [One paratrooper] fired 10 dum-dums into the crowd but as he still had his official quota he got away with saying he never fired a shot.” Of the original statement this paratrooper gave to the Widgery Inquiry, “his statement was taken from him, torn up and replaced 10 minutes later by one ‘bearing no relation with fact’ but, he was told, would be the one used when he took the stand” (BBC News, 2000).

The Saville Inquiry interviewed more than 900 witnesses over seven years. At the time, it was the most expensive legal investigation in British history. The report was finally published on June 15, 2010. The report found:

- “‘The firing by soldiers of 1 Para caused the deaths of 13 people and injury to a similar number, none of whom was posing a threat of causing death or serious injury.’”

- “‘We found no instances where it appeared to us that soldiers either were or might have been justified in firing.’”

- “The report added that no one threw, or threatened to throw, nail or petrol bombs at soldiers.”

- “The explanations given by soldiers to the inquiry were rejected, with a number said to have ‘knowingly put forward false accounts.’”

- “Members of the Official IRA fired a shot at troops, but missed their target, though it was concluded it was the paratroopers who shot first on Bloody Sunday.”

- “The report recounted how some soldiers had their weapons cocked in contravention of guidelines, and that no warnings were issued by paratroopers who opened fire.”

- “Speculation that unknown IRA gunmen had been wounded or killed by troops, and their bodies spirited away, was also dismissed. There was no evidence to support it and it would surely have come to light, the report said.”

- “Lord Saville concluded that the commander of land forces in Northern Ireland, Major General Robert Ford, would have been aware that the Parachute Regiment had a reputation for using excessive force. But he would not have believed there was a risk of paratroopers firing unjustifiably.”

- “The commanding officer of the paratroopers, Lieutenant Colonel Derek Wilford, disobeyed an order from a superior officer not to enter troops into the nationalist Bogside estate; while Lord Saville found his superior, Brigadier Patrick MacLellan, held no blame for the shootings since if he had known what Col Wilford was intending, he might well have called it off” (PA Reporter, 2022).

The publication of the Saville Inquiry report did not end the fight for justice. As of December 2023, a trial date had not been set for one former paratrooper to face trial at Belfast Crown Court. While the Troubles, the ethno-nationalist conflict, can be said to have ceased in 1998 after approximately thirty years, some families and loved ones are still waiting for justice.

Bibliography

BBC News. (2000, June 12). Soldiers Urged to “Get Kills.” http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/uk_news/northern_ireland/787902.stm

Conflict Archive on the Internet – Ulster University. (2001, December 11). ‘Bloody Sunday’, 30 January 1972 – Summary of Main Events. https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/events/bsunday/chron.htm

Conflict Archive on the Internet – Ulster University. (2001, December 11). A Chronology of the Conflict – 1972. https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/othelem/chron/ch72.htm

Conflict Archive on the Internet – Ulster University. (2001, January 31). Report of the Tribunal appointed to inquire into the events on Sunday, 30th January 1972 [Widgery Report]. https://cain.ulster.ac.uk/hmso/widgery.htm

PA Reporter. (2022, January 27). The Main Findings of the Bloody Sunday Inquiry. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/martin-mcguinness-provisional-ira-stormont-northern-ireland-parachute-regiment-b2001859.html