Zen Buddhism’s enigmatic teachings and its masters have influenced East Asian art, philosophy, and poetry for over a thousand years. However, the entire tradition traces itself back to one legendary man, credited not only with bringing Zen to China but also with the development of a new martial art at Shaolin Monastery, which would eventually spread worldwide: Kung Fu. The story of master Bodhidharma is enshrouded in legend and embellishment but provides a window into the heart of Chinese culture and one of its most famous arts.

Bodhidharma’s Journey to China

According to one legend, Bodhidharma was born in southern India during the 5th or 6th century CE. He came of age almost a thousand years after Siddhartha Gautama—more commonly known as the Buddha—when Buddhist teachings had become the dominant tradition in India. However, the rise of Hindi devotional movements, such as Bhakti, and a resurgence of Brahmanical traditions had begun to compete for dominance. Over only a few centuries, Buddhism would suffer a complete decline in India.

Buddhism was able to escape extinction by gradually spreading around Southeast and East Asia along the Silk Road and maritime trade routes. By the time Buddhism had essentially disappeared in its land of origin, it had become firmly established in places like Tibet, Thailand, and—most important for our story—China.

Although Buddhism had come to China early in the first millennium CE, one of the traditions that would define Chinese Buddhism—Zen—did not arrive until centuries later. Known in China as Chan, the name is a rendering of the Sanskrit dhyana, meaning meditation or tranquility. When the tradition eventually made its way to the Japanese, Chan was pronounced as Zen. The link between Japan, China, and Indian Buddhism was accomplished by one enigmatic, cantankerous, and deeply realized monk.

The Arrival in China

Although Chinese sources differ on Bodhidharma’s origins, indicating his quasi-legendary character, biographers agree Bodhidharma showed spiritual inclinations from a young age and eventually left home to become a Buddhist monk. Upon completion of his training, his master instructed him to travel to China to spread Buddhism.

Legend has it Bodhidharma arrived in southern coastal China, perhaps in Guangdong or Guangxi, and gradually traveled north, spreading the Dharma. Although Buddhism had been introduced to China several centuries earlier, it was still integrating itself into the culture alongside native Chinese traditions like Daoism and Confucianism. The 5th and 6th centuries CE was an important moment in this synthesis and saw the rise of several Buddhist schools and the translation of important texts into Chinese.

The spread of Buddhism was largely due to state patronage, with powerful emperors such as Emperor Wu of Liang supporting the religion. Fittingly, legends say that Bodhidharma’s journey took him to this Emperor’s court. In a symbolic encounter representative of Zen’s ethos, the emperor asked about the merit accrued from financially supporting Buddhism. Bodhidharma replied that true merit came only from the direct experience of enlightenment.

Afterward, Bodhidharma traveled south, crossing the Yangtze River. According to legend, he sailed across on a single blade of grass, gliding freely across the water just as he floated freely through the effusive mind of awakening.

Shaolin Monastery and Zen Meditation

Bodhidharma continued traveling and eventually arrived at the Shaolin Monastery in the Songshan Mountains of Henan Province. The monastery, established in 495 CE, was already an established center of Buddhist learning and practice. However, Bodhidharma’s arrival marked the beginning of a new chapter in the monastery’s history.

When he reached the complex, Bodhidharma first rested from his arduous travels and entered an intensive meditation retreat. The annals say that he spent nine years meditating in a cave near the temple. Zen’s approach to meditation involves a direct, unmediated experience of the mind’s true nature. Seeking such a goal, Zen meditation proceeds through an objectless, effortless contemplation, letting awareness simply behold that which arises in the space of mind and body.

Bodhidharma entered retreat and meditated by unblinkingly staring at a blue wall — resting the mind in its natural state of awareness until the great clarity of enlightenment deepened in him. His continually drooping eyelids angered him so much that he ripped off his eyelids and cast them down — mystically taking root and sprouting up as China’s first tea plants. Since then, tea and Zen have been inseparable.

The Development of Kung Fu

After his retreat, Bodhidharma noticed the Shaolin monks were physically weak due to their sedentary lifestyle. Their practice after all involved sitting for many hours a day and, aside from drawing water and walking for alms, their physical state was almost totally neglected. Bodhidharma’s vision of awakening, however, was radically different. His idea of Zen was one of complete integration of mind and body, inner and outer, everyday and esoteric. This emphasis on Zen continues to appeal to a modern audience with its poetry and aesthetics of simplicity and the vibrancy of the quotidian.

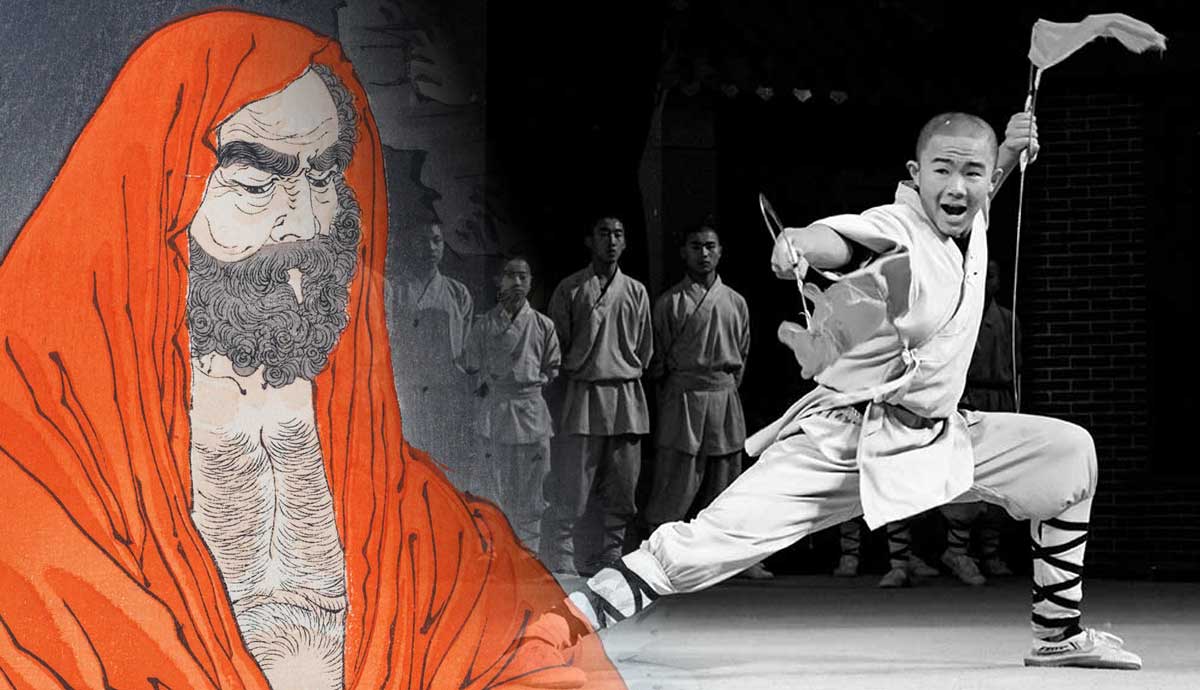

Bodhidharma taught the Shaolin monks a series of physical exercises to increase strength, flexibility, and vitality. These movements—known as Yi Jin Jing and Xi Sui Jing—were not just for external strength but also tools for building mindful awareness and concentration. In essence, these techniques were a meditation.

Over time, Bodhidharma’s physical exercises evolved into more structured and sophisticated forms of martial arts. The monks at Shaolin Monastery used this basis to develop techniques for self-defense, combat, and physical conditioning, drawing inspiration from various sources, including Indian martial arts and indigenous Chinese fighting styles. The unique style of the Shaolin Monastery became known as Kung Fu.

Myth vs. Historical Fact

As compelling as this story is, the connection between Bodhidharma and Kung-Fu is a blend of loose historical facts and centuries of embellishment. While his status as the first patriarch of Zen is more well-documented, his role in the creation of Kung Fu appears to be the stuff of later legend. However, like all legends, this tale is deeply significant for how we understand the nature of Zen and Chinese spirituality.

The ethos of Zen is orientated around the non-difference between sacred and profane, inner and outer, mind and body. This philosophy of śhunyatå or emptiness is about the total interpenetration and interrelation of all phenomena. Such a view conditions not only Zen meditation, but its artistic and poetic expressions. Kung fu’s coordinated physical movements are another expression of this worldview.

Whether or not Bodhidharma taught a proto-Kung fu, this legend points to a deep current in Chinese religion — the integration of inner spiritual practice and outer physical discipline. Native Chinese traditions, like Daosim, had long developed interlinking systems of physical movements, breath-work, and meditation. These systems are now popular the world over, Tai-Chi/Qi Gong being the most visible. The link between martial arts and what we may broadly call spirituality underscores that; health benefits aside, the purpose of these practices and traditions is inner discipline and transformation.

The Shaolin Monastery and Kung Fu Worldwide

The Shaolin Monastery has become a Chinese cultural icon, representing martial arts, discipline, and spiritual practice. Despite being in a Communist and officially atheist China, this Buddhist center continues to attract tens of thousands of tourists annually. One wonders if it is a sign that the deep currents of Chinese Buddhism can only be repressed for so long.

Today, kung fu is practiced by millions of people around the world, transcending cultural and geographical boundaries. Kung fu schools and training centers can be found in almost every country, offering classes that range from traditional styles, such as Shaolin kung fu and Wing Chun, to modern adaptations designed for competitive sports and self-defense. These events often highlight forms (taolu), sparring (sanda), and weaponry, showcasing the martial art’s rich variety and depth.

The influence of kung fu extends into popular culture as well. Martial arts films, many of which feature kung fu, have played a significant role in bringing the art to a global audience. Iconic figures like Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan, and Jet Li have popularized kung fu through their movies, inspiring generations to take up the practice. These films often depict the philosophical and moral lessons of kung fu, further enhancing its appeal.

Conclusion

Despite its commercialization and adaptation, the core orientation of kung fu remains intact. Respect for tradition, the pursuit of self-improvement, and the cultivation of both body and mind continue to define the practice. The legend of Bodhidharma and the origins of kung fu offer deep insight into the fusion of Zen Buddhism and Chinese martial arts. Whether fact or fiction, this story underscores the profound connection between spiritual practice and physical discipline in Chinese culture, illustrating how ancient traditions can endure and evolve while maintaining their essential values.