Of all the works by Bosch, none is more fascinating than the painting known as Garden of Earthly Delights. A work of which we do not even know the original title. It is unsettling not only because the subject matter is so enigmatic, but also, because of the remarkable modern freedom with which its visual narrative avoids all traditional iconography. Bosch’s paintings are fantastical in the most literal sense of the world. His artwork has both fascinated and inspired artists for several hundred years.

Hieronymus Bosch: Painter of the Garden of Earthly Delights

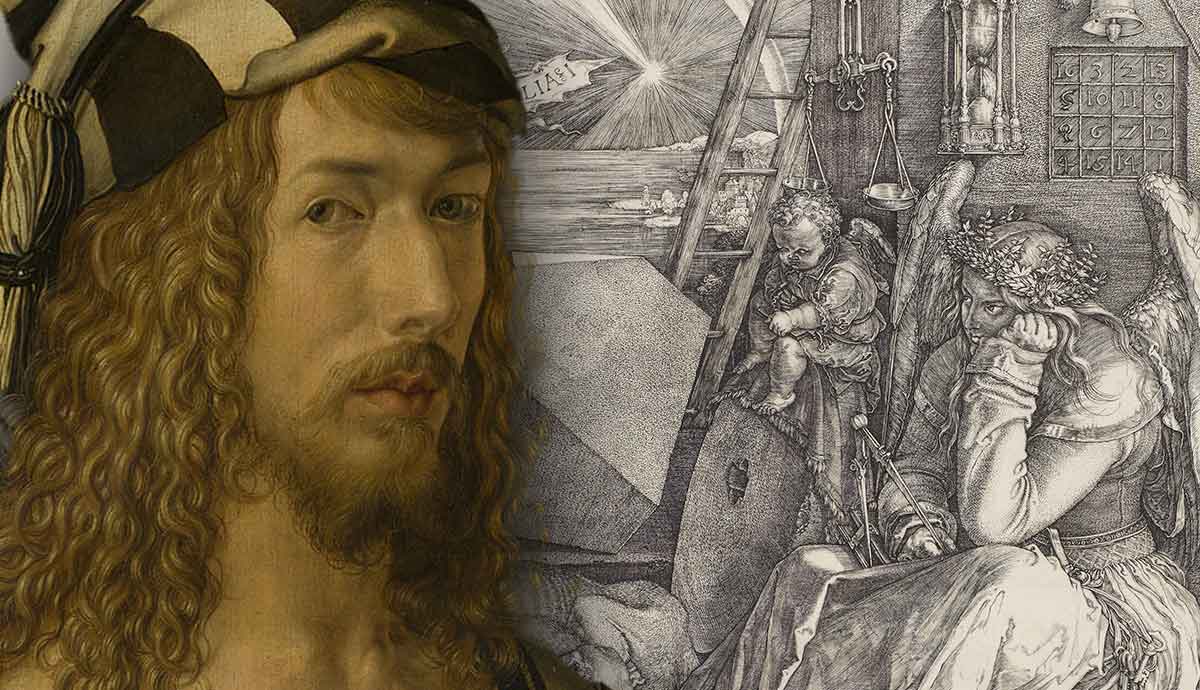

Hieronymus Bosch is one of the most mysterious figures in art history. Bosch, breaking with all the traditions of European religious art, depicted horrors in a manner that centuries later influenced the Surrealists.

Hieronymus Bosch lived from 1450 to 1516. He was named after his native town, Den Bosch, in the southern part of the Netherlands, where he lived and worked. Recurring themes in many of his paintings are death, doomsday, and hell. The Garden of Earthly Delights is one of his most famous paintings. It is a triptych depicting heaven and hell. The painting has been on display at the Prado Museum in Madrid since 1939.

Bosch’s Influence on 16th Century Painters

Exactly because Bosch was a distinctly unique and visionary artist, his influence did not spread as widely as that of his other major contemporary painters. However, later artists incorporated elements of Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights into their work.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525-1569) directly acknowledged Bosch as an important influence and inspiration. Multiple elements of The Garden of Earthly Delights’ inner right panel appeared in several of his most popular works.

Bruegel’s painting Mad Meg (c. 1562) depicts a peasant woman leading an army of women to pillage Hell, while his The Triumph of Death (c. 1562) echoes the monstrous Hellscape of The Garden, utilizing the same unbridled imagination and fascinating colors.

While the Italian court painter Giuseppe Arcimboldo (c. 1527–1593) did not create Hellscapes, he painted a body of strange and “fantastic” vegetable portraits; i.e. heads composed of plants, roots, webs, and various other organic matter. These strange portraits echoed a motif that can be partly traced to Bosch’s willingness to break from strict and faithful representations of nature.

Bosch’s Influence to 20th Century Art

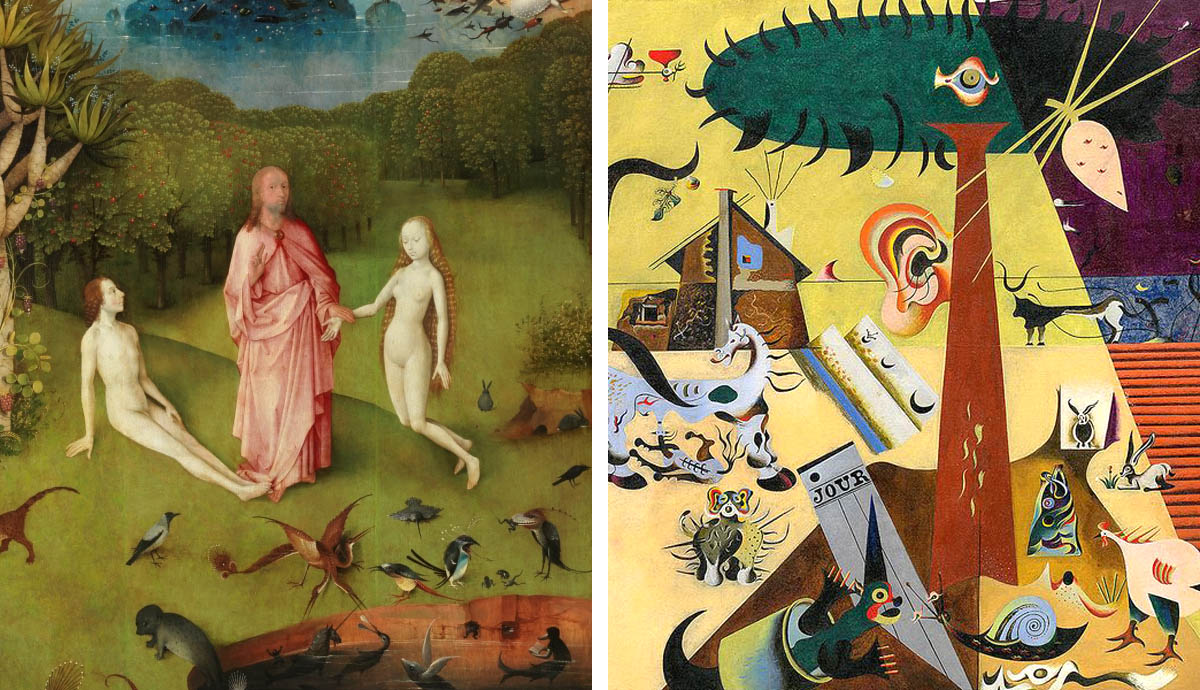

During the early 20th century, Bosch’s work enjoyed a popular resurrection. The early surrealists’ fascination with dreamscapes, the autonomy of the imagination, and a free-flowing connection to the unconscious brought about a renewed interest in Bosch’s work. The Dutch painter’s imagery influenced Joan Miró and Salvador Dali in particular. Both knew his paintings firsthand, having seen The Garden of Earthly Delights in Prado. Both regarded him as an art-historical mentor.

The Surrealist movement was responsible for rediscovering Bosch and Breugel, who quickly became popular among the movement’s painters. René Magritte and Max Ernst were also inspired by Bosch’s Garden.

The Surrealist Movement

Surrealist art flourished between the 1920s and 1930s, characterized by a fascination for the bizarre, the incongruous, and the irrational. As a movement, Surrealism was closely related to Dada and several artists were associated with both. Although both movements were strongly anti-rationalist and much concerned with creating disturbing or shocking effects, Dada was essentially nihilist, while Surrealism was positivist in spirit.

Surrealism originated in France. Its founder was the writer André Breton who officially launched the movement with his first Manifeste du Surréalisme, published in 1924. The movement sought to release the creative powers of the subconscious mind or as Breton put it “to resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality”. Surrealism embraced a large number of different and not altogether coherent techniques, aimed at breaching the dominance of reason and conscious control to unleash primitive urges and imagery. Breton and other members of the movement drew liberally on Freud’s theories concerning the subconscious and its relation to dreams.

Bosch’s Modernity

There is something strangely modern about Bosch’s turbulent and grotesque fantasy. It is no surprise that his appeal to contemporary taste has been strong. Apart from the riot of fantasy and that element of the grotesque that caused the surrealists to claim Bosch as their forerunner, the haunting beauty of his genuine works derives largely from his glowing color and superb technique, which was much more fluid and painterly than that of most of his contemporaries. Bosch was also an outstanding draughtsman, one of the first to make drawings as independent works.

Undoubtedly, Bosch was considered one of the earliest surrealist artists. He often employed images of devils, human-like creatures, and mechanical forms to wake fear and confusion. These works contained complex, highly original, imaginative, and dense symbolic figures portraying the evil of mankind. These images were considered obscure in his time. However, exactly these obscure images promoted him to the throne of the forefather of Surrealism.

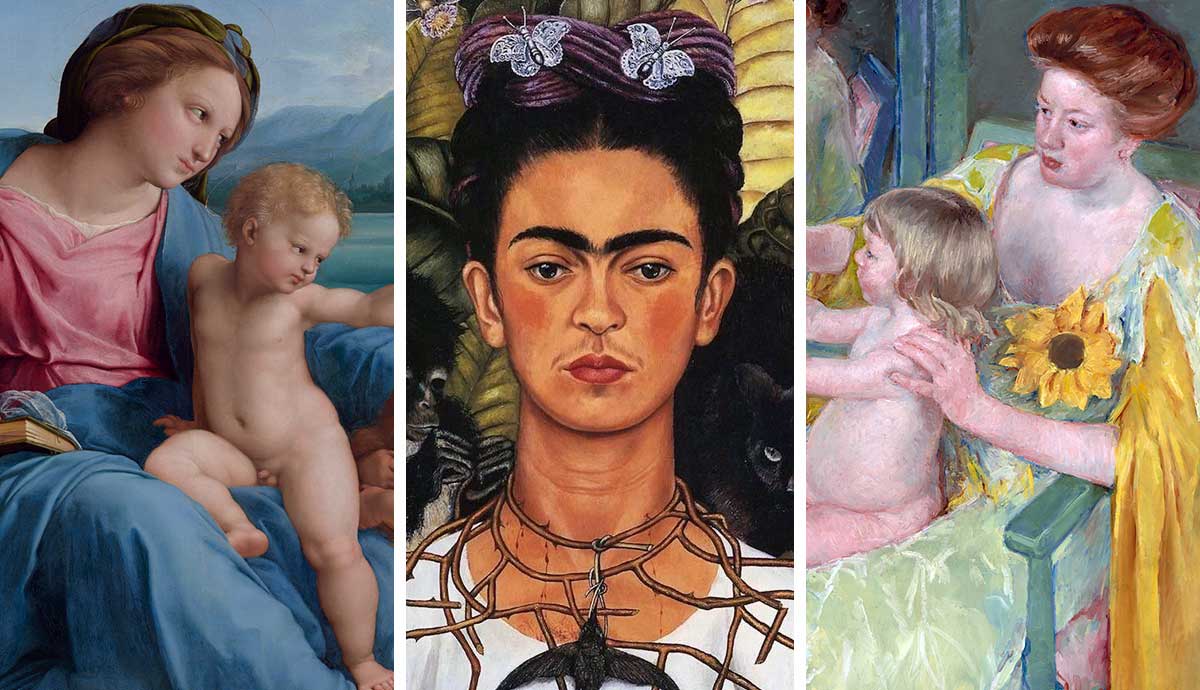

Bosch and Joan Miro

The resemblance between Miro’s “chimerical bestiary” in The Tilled Field and the strange animals found in Bosch’s paintings has been proven by art critics. We can easily find many similarities with the Garden of Earthly Delights. The stylized forms in the background of Bosch’s painting seem to have inspired the plant forms at the left of Miro’s painting. The same flock of birds appears in both. Miro’s plants are a stylized agave and a composite structure carrying the flags of monarchical Spain, Catalonia, and France; Miro’s own mixed loyalties. In the right foreground of each painting, is a pool from which creatures emerge. Bosch’s painting refers to the creation, while Miro’s choice of creatures around the pond suggests a more modern sequence of evolution.

At the right-hand side of Miro’s painting is a tree with an ear and an eye. A pair of giant disembodied ears appear in the right-wing of Bosch’s Garden, while a tree form below them has a human face (Tree-man). The idea of the observing eye appears several times in Bosch’s paintings. For example, in the left-wing of the Garden is a central tree motif. There an owl looks out of an eye-like hole in a sphere.

The motif of the observing eye is also repeated in Miro’s Catalan Landscape. There, the eye is attached to a spherical tree (compare again with the left-wing of the garden of earthly Delights).

It is worth mentioning that in 1928, Miro went to the Netherlands and brought back postcards of paintings by Jan Steen and other Dutch masters which he used as a starting point for paintings done later that year. It seems very possible that Miro was partly motivated to make this journey by an existing admiration for Bosch and the desire to see this artist’s native land.

As Gerta Moray has indicated, when Breton wrote the Surrealist manifesto he seemed unaware of Bosch. In his list of surrealists avant la lettre, he names only three non-living artists, Uccello, Seurat, and Moreau. When Max Ernst published Max Ernst’s Favourite Painters and Poets, Bosch and Bruegel had become Surrealist heroes. They may well have been introduced to the group initially by Miro who was in the best position to know their work.

Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism (1936) and the Proto-Surrealists

In 1936, curator and director Alfred H. Barr staged the grand show Fantastic Art, Dada Surrealism at MOMA, New York. Barr succeeded rather well in putting surrealism on the map of American and also international audiences. His vision of surrealism would reverberate internationally for decades to come.

Barr proposed two concepts in particular which would prove immensely successful judging by how quickly they became part of the discourse surrounding surrealism. The first was the historicity of surrealism. The second was its fantasticity or the intimate association with the fantastic.

The historicity of Surrealism was built upon the idea that the movement was a modern iteration of an older phenomenon or that it belonged to a long tradition with predecessors called the proto-surrealists. Many of the proto-surrealists were 15th and 16th-century European masters, such as Hieronymus Bosch, linearly related to the 20th-century group. Barr made this relation visually explicit by opening the exhibition with old masters.

The catalog followed this categorization and emphasis on historical linearity. In his introduction, Barr distinguished between the section: ‘Fantastic art of the past’, which began with “Hieronymus Bosch working at the end of the Gothic period, [who] transformed traditional fantasy into a personal and original vision which links his art with that of the modern Surrealists” and the section: ‘Fantastic and anti-rational art of the present’, which began with Dada.

Dali and Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights

Scholarly interest in Bosch revived at the turn of the 20th century and mushroomed after a major exhibition of his works in Rotterdam in 1936. Popular writers soon discovered him and proclaimed him a 15th-century Surrealist expressing his repressed desires and dreams through bizarre symbols.

Salvador Dali, one of the greatest surrealist painters, could very well have defined himself as “anti-Bosch.” Still, it is difficult for art historians not to acknowledge some sort of kinship in the surreal world of both painters. In fact, Dali studied Bosch’s paintings and techniques. For example, in The Great Masturbator, a famous Dali painting, the unusual rock formation resembling a face seems to be inspired by a similar shape in the left panel of The Garden of Earthly Delights.

Dali’s painting style is unique. It incorporates lines and shapes creating strong movements, thereby making his painting more dynamic. In The Great Masturbator, there is a dynamic flow that leads the viewer’s eyes around the painting and thereby helps the viewer’s immersion into the piece.

“Like Bosch, Dalí was a very realistic painter, whose creativity transformed things,” states the director of the Noordbrabants Museum, Charles de Mooij and adds: “The Surrealists were changing normal into abnormal things, just as Bosch did. Ultimately, though, they only took one part of Bosch: they didn’t take his [religious] message, but admired him for the strange, original forms that he created.”