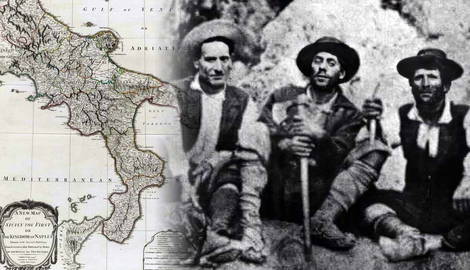

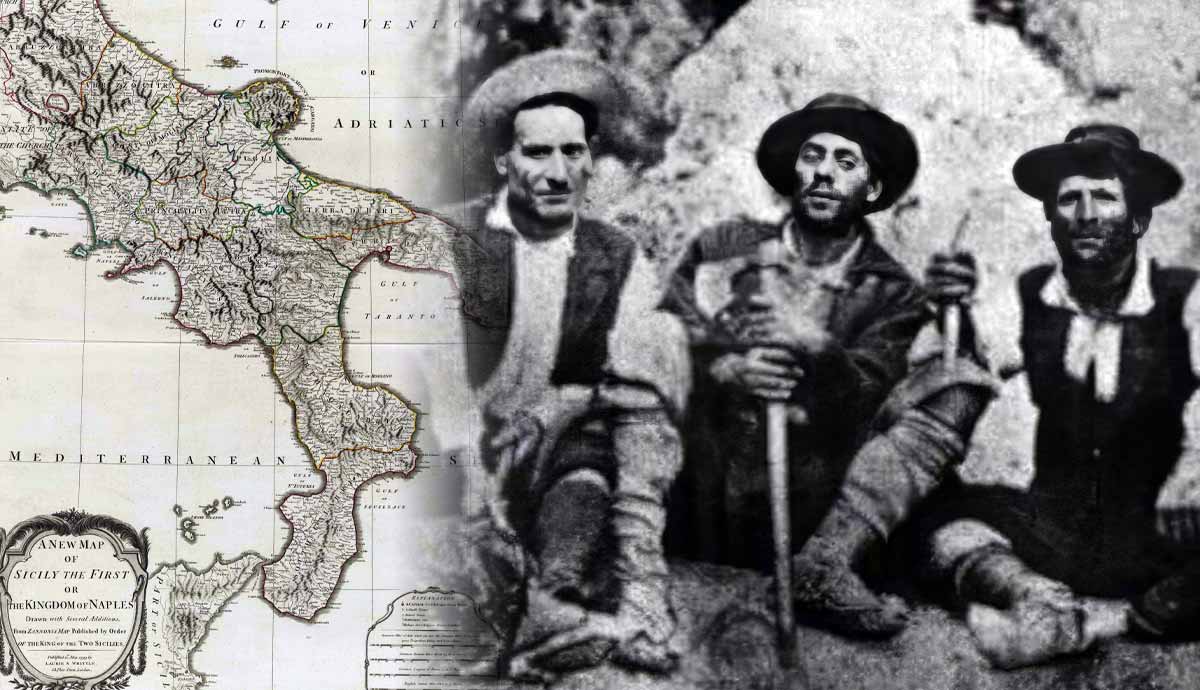

In February 1863, in a letter sent to his wife from southern Italy, Nino Bixio commented, “The mass of the population is at least three centuries behind ours.” At the time, Bixio was a member of the special parliamentary commission tasked with investigating the causes of a phenomenon threatening the stability of the newly formed Kingdom of Italy: southern Brigantaggio.

In the aftermath of the unification, in the mainland of the former Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, impoverished peasants and Bourbon soldiers formed armed bands to fight what they perceived as a forced annexation to the unified state. The phenomenon weakened the Italian nation-building process and had a lasting impact on the country’s public discourse.

The Unification of Italy & the Brigantaggio

On March 17, 1861, when the parliament in Turin proclaimed the establishment of the Kingdom of Italy, the new Italian government faced a long and strenuous task: merging a diverse group of territories and populations into a single national entity. “We have made Italy,” famously declared Massimo D’Azeglio, “now we must make Italians.” Thus, in the years following the official unification of the Italian peninsula, the leaders of the Risorgimento set out to promote a sense of belonging and establish a solid link between state and civil society.

To foster national identity, the first Italian government, mainly composed of politicians of the former Kingdom of Piedmont-Sardinia and other northern regional states, opted to strengthen the centralization of the governmental structure, extending the Piedmontese administrative and judicial apparatuses to the rest of the peninsula. To the same end, high-ranking officials from Piedmont were appointed to the most strategic positions of the peripheral administration. The centralization policy, however, widened the already large economic gap between North and South.

In the 1860s, the industrialized northern territories of the peninsula were radically different from Sicily and the southern mainland, where around 70 percent of the population worked in agriculture. The former Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was also plagued by poverty, endemic diseases, and widespread illiteracy. The free-trade policies promoted by the government weakened the small manufacturing sectors of the South.

The worsening economic situation led to discontent, especially among the lower classes. The ensuing disillusionment with the Risorgimento and its promises caused a widespread wave of popular uprising commonly known as Grande Brigantaggio (Great Brigandage). In Campania, Molise, Apulia, Calabria, and Abruzzo, armed bands of brigands fought against local state officials and the Italian army. The Bourbon court in exile in Rome and the Catholic Church, fierce opponents of Italian unification, supported the brigands.

Until 1865, the Brigantaggio weakened the legitimacy of the new Italian nation, leading to a deep cultural and social divide between the South and the rest of the peninsula. The geographical dichotomy is known as Questione Meridionale (Southern Question). Similar to the so-called Roman Question, the post-unification southern rebellion directly challenged the nation-building experiment of the Risorgimento’s political leadership.

A Complex Phenomenon: The Causes of the Brigantaggio

In the southern part of the Italian peninsula, brigandage preceded the unification. Indeed, before the 19th century, banditry was already present in the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies as an endemic form of rural criminality. However, the scope and specific political features of the Great Brigandage were unprecedented, making the 1860s phenomenon intrinsically different from the previous semi-organized Brigantaggio.

In 1861, the violent reaction against the new central authority was the result of a series of different factors. Initially, the dissent of large sectors of the southern population stemmed from widespread dissatisfaction with the government’s land redistribution policy, the new tax system, and the introduction of mandatory conscription.

While the lower classes hoped that the collapse of the Bourbon monarchy would result in a more equal structure of agricultural production, ownership of the ancient feudal estates, the terre demaniali (land owned by the state), and the landed property of the Catholic Church passed from the nobility to the wealthy bourgeoisie, whose member had supported the nationalist cause. The new status quo also led to the abolition of the so-called common uses of the terre demaniali. The discontent with the lack of radical land reforms eventually originated the belief that the unification had benefited solely the higher classes.

The social and political instability following the abrupt end of the Bourbon leadership exacerbated the already volatile post-unification situation in the South. After the disbandment of the Bourbon troops, numerous soldiers, unwilling to enlist in the army of the newly formed kingdom, joined the bands of bandits active in the mountains and countryside. The Bourbon soldiers firmly rejected the Risorgimento and its liberal ideals. During Giuseppe Garibaldi’s Expedition of the Thousands in the southern portion of the peninsula, they had fought what they perceived as a “foreign invasion.” In the aftermath of the unification, the soldiers saw the Brigantaggio as a means to protest the forced annexation to Piedmont and the ensuing “occupation.”

During the Bourbon monarchy, the king, as an embodiment of social unity, had legitimized the existing hierarchies and guaranteed order and stability. On the other hand, the government’s failure to establish more equal relations of agricultural production led many peasants to identify the new institutions with social injustice. In 1860, in the small Sicilian town of Bronte, the brutal repression of a popular upheaval demanding the distribution of communal land foreshadowed the southern lower classes’ lack of trust in the new state and order stemmed from the Risorgimento.

The Massari Report

In the summer of 1861, the guerrilla war of the brigand bands against the Italian state and its army reached its peak. Along the Apennine mountain range, they occupied villages, burned town halls, and attacked and kidnapped state officials. The contingent of Italian troops stationed in the southern provinces could not contain the uprising and restore public order. To compensate for the lack of military personnel on the ground, the government enlisted local men and formed National Guards. The underequipped regional militia, however, ultimately resulted similarly ineffective against the outlaws.

The following year, while the warfare waged by the brigands against the state was still underway, Giuseppe Garibaldi organized a new expedition in the South to conquer Rome and complete the unification of the Italian peninsula. Fearing that Garibaldi’s exploit might result in a wave of intense popular agitation against the Piedmontese leadership of the Risorgimento, the government declared a state of siege in the southern Italian territories. The harsh measure inaugurated a period of ruthless repression of the brigandage.

To identify more effective means to end the Brigantaggio, the parliament also appointed a special commission of inquiry tasked to investigate the nature and structural features of the phenomenon. In January 1863, the members of the commission began touring the former territories of the Bourbon Kingdom. In the following months, they visited many urban centers and rural areas of the South, collecting petitions and requests from local officials, functionaries, and politicians.

As the representatives of the Italian parliament ventured into the still largely unknown southern provinces, they were struck by the dramatic conditions of the local inhabitants. In their letters and reports, the members of the special commission began to create a picture of the South as backward and archaic, laying the foundations of the future mainstream narrative on the Mezzogiorno.

“The mass of the population is at least three centuries behind ours,” wrote Nino Bixio to his wife. He later added: “This is a country that should be destroyed or at least depopulated and its inhabitants sent to Africa to get themselves civilized!” Aurelio Saffi voiced a similar opinion, remarking that the former Kingdom of the Two Sicilies was a “legacy of barbarism to 19th century civilization.”

In his final report, Giuseppe Massari, the commission’s secretary, identified the main cause of Brigantaggio as the poor living and working conditions of the peasants. He declared that the phenomenon was especially widespread in areas where a few landlords owned the majority of farmable land. Massari also emphasized the deep ties between the local administration and the previous Bourbon monarchy.

The Massari Report suggested public works (such as the construction of a network of roads and railways) as a possible means of improving the South’s economic conditions. More importantly, the commission of inquiry introduced the “crime of brigandage” into the kingdom’s penal code.

Known as the Pica Law, the new legislation allowed the government to implement harsh measures in the provinces “in a state of brigandage” and gave the military courts the power to try the brigands. According to the anti-Brigantaggio legislation, the civilians accused of manutengolismo (aiding and abetting) also faced arrest and execution.

The Italian Army vs. Brigand Bands: A Civil War?

After the introduction of the Pica Law, the already bloody war between the Italian army and the brigand bands intensified. During the summer of 1861, the Piedmontese troops made mass arrests and executions among the civilian populations, hoping to erode their support for the outlaws. In Campania alone, the army combed several villages suspected of harboring and helping the brigands. At Pontelandolfo, forty-eight people died after the army set fire to the town in retaliation to the killing of about forty soldiers.

“This episode of warlike terror lasted for an entire day,” later wrote Officer Angiolo De Witt, “the punishment was horrific, but the act that caused it was even more horrific.”

In 1863, the Italian army doubled its efforts to eradicate Brigantaggio from the South. For the following two years, countless brigands and civilians were jailed and branded as “enemies at war with the state.” It is estimated that more than five thousand people died during the conflict.

While the draconian measure proved effective in the fight against the guerrilla against the state, the ensuing regime of terror ultimately worsened the deep mistrust and resentment of the southern population for the unified Italian kingdom. Shortly after the approval of the Pica Law, in a commentary on the Massari Report, Carlo Piccirillo, a Jesuit priest, referred to Brigantaggio as a “civil war.”

Piccirillo also protested that the anti-brigandage legislation had failed to recognize the political nature of the phenomenon: “Could there be any doubt for anybody that Brigandage only has a political cause, and that it is nothing less than the defense of [southern] independence?”

The social and anti-institutional features of Brigantaggio also permeated some folk tunes sung by the brigands themselves: “You have paper, pen and ink pot to punish these poor souls, I have got gunpowder and bullets, when I shoot: justice I make for those who have nothing.”

Counter-Revolution: The Bourbons & the Brigantaggio

Despite the Italian state’s unwillingness to define Brigantaggio as a politically motivated conflict, the alliance between the brigand bands and the Bourbon court in exile was a vital component of the post-unification uprising. After “liberating” towns and villages in the mainland South, the brigands usually displayed symbols of the Bourbon monarchy.

In the aftermath of the unification, Francis II, the last king of the Two Sicilies, sought to use the guerrilla waged by bandits and peasants against the Italian state to his advantage, hoping to galvanize the southern population in a mass revolt that would reinstate him to his throne. Despite the backing of the Catholic Church, which gave his claim a “sacred” character, Francis II ultimately proved unsuccessful in eroding the Kingdom of Italy’s hold in the South.

One reason the Bourbon king failed was the fraught collaboration between the brigands’ leaders and the foreign volunteers recruited to coordinate the local bands. The formation of the Kingdom of Italy had alarmed the European counter-revolutionary front, whose members considered the movement for Italian unification a threat to the status quo established in 1815 at the Congress of Vienna. Thus, as soon as 1860, hundreds of men arrived in Italy to participate in Francis II’s conspiracy against the Italian government.

However, the first military enterprises of the new “Bourbon troops” were largely unsuccessful. The rivalry between the European volunteers and the brigand commanders slowed the legitimist front’s advance. In 1861, for example, the clash between Carmine Crocco and José Borjes ended with the defeat of the Spanish General, who was captured and shot by the Italian army at Tagliacozzo, a small village in Abruzzo.

The Brigantaggio & the Southern Question

Around 1865, the Italian army finally managed to contain the southern rebellion. However, the open and violent rejection of the nation-building process by large sectors of the population cemented the division between North and South, resulting in a fragile national identity.

In the southern portion of the peninsula, folk songs, rumors, and legends develop a rich mythology around the brigands. Band leaders such as Carmine Cocco and Chiavone were celebrated as Robin Hood figures. Over the following centuries, the pro-Brigantaggio southern narrative created a long series of histories, counter-histories, and revisionist theories revolving around the claim that the economic and social problems of the South were the direct result of the Risorgimento.

On the other hand, the first studies of the Brigantaggio, mostly written by officers of the Italian army, created an image of the South as “Other.” In 1860, Luigi Carlo Farini, then Minister of the Interior of the Kingdom of Piedmont, wrote to Count Camillo Benso di Cavour: “Ah, my friend, what sort of countries are the Molise and the Terra del Lavoro! What barbarism! This is not Italy! This is Africa.”

Similarly, drawing on ethnocentric imagery, these first historians portrayed the bandits as “black, animal, feminine, primitive, deceitful, evil, perverse, irrational.” In 1864, Count Alessandro Bianco di Saint Jorioz, a Piedmontese officer, declared that brigandage “is the struggle between barbarism and civilization.” Criminologist Cesare Lombroso, who was stationed in the South as an army doctor, later analyzed the skulls of dead brigands to identify the physiognomical traits of their “primitiveness.”

The so-called Southern Question endured long after the end of the post-unification Brigantaggio. In his Prison Notebook, for example, Antonio Gramsci quoted the failed attempt to involve the backward and reactionary South in the Risorgimento as one of the reasons for Italy’s “democratic deficit” that would eventually lead to fascism. Today, the divide between North and South is still a matter of heated public and historiographic debates in Italy.