Bruce Nauman’s creative genius has graced every medium imaginable. Widely recognized for his irreverent light installations, the chameleon-like artist possesses no quintessential style, instead morphing to his materials as if predetermination. From unsetting sculpture to photography, video, and drawing, today Bruce Nauman continues to defy description as intensely as his genesis sixty years ago.

Bruce Nauman’s Early Life and Work

Nauman’s turbulent childhood began in 1940s Fort Wayne, Indiana. His father an engineer, the artist drifted from one podunk Midwestern town to the next, never truly fitting in. He showed very little interest in visual art, but instead favored musical instruments, an early testament to his media versatility. During the 1960s, he studied mathematics and physics with a minor in Painting at the University of Wisconsin until his graduation in 1964. Two years later, he completed his MFA from UC Davis. Among his instructors were avant-garde pioneers Manuel Neri, William T. Wiley, and Robert Arneson, sculptural non-conformists pushing precincts through a relaxed and broad curriculum. Nauman also resolved to abandon painting altogether while attending Davis, claiming its abundant materials simply “got in the way.” Slender with a muted color palette, his last canvas Untitled (1965) bears little resemblance to the vibrant body of work the artist is known for today.

The late 1960s marked an experimental time for Bruce Nauman. He conceived his first fiberglass sculptures in 1965, and took an unconventional approach to cast and molding. Using polyester resin, Nauman created an Untitled series assessing his new medium’s physical potentiality, monochromatic models cast twice in fiberglass. Since it was based on a handmade clay prototype, however, he also took a large risk handling its fragility. His gamble would inevitably pay off, though. Nauman worked tirelessly at his career’s onset in the 1960s to focus on an idea his contemporary conceptualists had begun postulating: creative techniques superseded end results as a source of significance. “I was an artist and I was in the studio, then whatever I was doing in the studio must be art,” Bruce Nauman once remarked about his early years. “At that point, art became more of an activity and less of a product.”

How Process Art Inspired Nauman

Nauman ascribes to an artistic genre hyperfocused on methodology. Dubbed “process art,” the style favors technique over aftereffects, viewing manual labor as creativity within itself. Many credit its genesis to the monumental moment Jackson Pollock dripped paint onto a blank canvas, though process art dates back further to roots in Dadaism. Rather than fixating on end results, process artists take pleasure in their media’s physicality, relishing a routine from start to finish. Assembling, classifying, and patterning were all equally significant facets in creating a masterpiece. Reduplication was particularly paramount throughout Nauman’s mixed-media work during the late 1960s and 1970s. Akin to scholar Marshall McLuhan’s famous phrase, his medium was indeed his message. Nauman formulated thousands of nuanced tales through light, video, and sound installations, simultaneously examining his artistic role while he fulfilled it.

Nauman’s First New York Exhibition

The Leo Castelli Gallery hosted Nauman’s first New York exhibition in 1968. Filling the tiny space with his newfound experiments, the artist showcased rudimentary light and video installations to demonstrate his artistic dexterity, like his now-famous Neon Templates of the Left Half of My Body Taken at Ten Inch Intervals (1966). However much faith Castelli held in him, however, critics met his work with mixed reviews. European curators showed a strong affinity for Nauman since the beginning. Dissidents in America, particularly New York, weren’t nearly as kind. Writing in relation to his show at The Leo Castelli Gallery, historian Robert Pincus-Witten proclaimed Nauman’s output “infantile narcissism.” Likely, his status as a San Francisco outsider prompted territorial jealousy. Or, maybe New York City simply wasn’t ready for his natural foresight. Nauman would nevertheless prove opponents wrong during his next decade in California.

Why Bruce Nauman Shunned Minimalism

Minimalism occupied hegemonic prestige during Bruce Nauman’s 1960s ascension to fame. For this same reason, the sculptor sought to consciously counteract the prevailing creative order, which included distinguished figures such as Barnett Newman and Donald Judd. By then, the archetype of an artist had become a sober caricature of perfectionist tendencies, a phenomenon Nauman described as increasingly self-aggrandizing. “I was surprised at how badly made they were,” he once critiqued Judd’s early work in a NY Times interview. In comparison to rigid, abstract, and flat formalist techniques, Nauman’s work was perceivably lighthearted, a flawed mirror depicting his authentic artist journey. Though never confirmed, historians even hypothesize his elaborate titles to be a direct subversion of conformist tendencies to label a piece “untitled.” Strapped with his dynamic multimedia arsenal, the provocateur shook modernity to its core by pledging to follow his own code of conduct.

By the early 1970s, Nauman’s career soared to unprecedented heights. He moved to Pasadena, plunged himself into art’s performative aspect, and began branching out in his social circles. Among his inspiring peers were musicians and dancers, from whom Nauman learned to further hone in on his creative process. His neon blue and red light sculpture The True Artist Helps the World by Revealing Mystic Truths (Window or Wall Sign) (1967) best exemplifies this period, its title scrawled within a dizzying spiral. Fusing fanciful language with commercial-produced materials, the artist evoked his mathematical background through viewer spatial relativity. From a distance, the red neon lining appeared to be a number six, with Nauman’s inscription visualizing only upon closer inspection. Highlighted in international forums such as Kunsthalle Bern and the Stedelijk Museum, Nauman’s institutional intrigue culminated in 1972, when he was offered his first official museum retrospective.

First Bruce Nauman Retrospective

The Los Angeles Art Museum and The Whitney co-curated Nauman’s touring extravaganza. Traveling cross-country from New York to Los Angeles, Marcia Tucker and Jane Livingston organized it with aspirations of reaching Europe. The exhibition’s collection featured new works Nauman completed during the late 1960s and early 1970s, including his first large-scale outdoor installation. Conceived to encircle LACMA, his La Brea/Art Tips/Rat Spit/Tar Pits (1972) perched adjacent to the prehistoric La Brea Tar Pits, illuminated in neon red and green. As his title may suggest, the piece contained anagrams of La Brea, a witty yet seemingly purposeless play-on-words. Yet triviality was exactly Nauman’s objective. Utilizing bold color contrasts, he highlighted linguistic puzzles to muddle everyday phrases and connotations. Despite his innovative achievements, however, some press nonetheless demonized Nauman’s retrospective as vapid. An increased media maelstrom led the artist to reconsider his flight path.

Nauman’s Final Years In California

Bruce Nauman is a notoriously private person. Whether positive or negative, he detested the spotlight, his paranoia increasing with his stardom. By the mid-1970s, prominence made the worst of him, and he severely decreased his artistic production. From this seclusion emerged incredible originality, however, including Nauman’s now-renowned text-based media. In fact, he conceived his 1974 neon sign Silver Livres in an attempt to regain control over his own methods, a counterpart to a large-scale exhibition he commemorated in Paris. Overlapping sets of red and green tubing revealed French anagrams for the term books, or “livres.” To mark an end to a memorable era, he also created his last Pasadena sculptural work Studio Piece in 1979. The scale-model hodgepodged previous materials through which Nauman explored his geometric inclinations. With that, he bid a nostalgic farewell to his native California, on the road to fresh beginnings in New Mexico.

When Nauman Moved To New Mexico

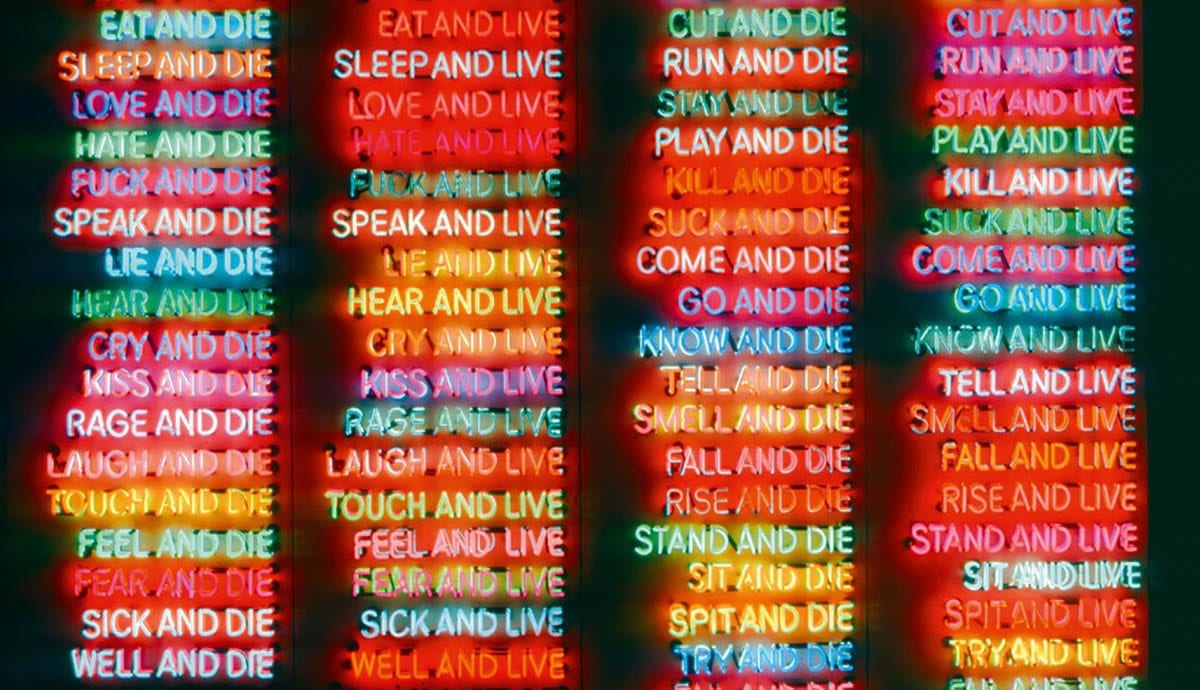

Nauman made a novel name for himself in the 1980s. Among San Miguel County’s luscious rolling hills, he built a new studio in a tiny village just south of Santa Fe named Pecos. There, he also developed an advanced pictorial language, replacing his simplified neon lights with more sinister modes of expression. In Violins Violence Silence (1981), yellow and pink neon tubing juxtapose six words in a loosely-formed triangle, counteracting musicality with serenity. By 1983, Nauman ran his ideas by The Stuart Foundation, who eventually erected his glowing Vices and Virtues on facades throughout San Diego years later. Unarguably his most famous work, Nauman’s breakout decade peaked with his 1984 One Hundred Live and Die. Four towering columns, 100 nonsensical phrases, and a medley of fluorescent pigment flawlessly epitomized our paradoxical human experience. A complex algorithm illuminated select words as others darkened to produce a visual euphony of language.

While public perceptions of the avant-garde metamorphosed, so did Nauman’s rising reputation. He celebrated several well-received solo-shows throughout the 1980s, including stints in Baltimore, Germany, and London. By 1987, he had solidified his growing interest in viewer participation with works like Clown Torture, a projection of grotesque videos centered on his characteristic motifs. Surveillance, stress, probing, and puns combined ad infinitum to disorient audiences, alluding back to Nauman’s fundamental obsession: repetition. After a hiatus of almost twenty years, he also returned to cast molding with his 1988 work Untitled (Two Wolves, Two Deers), made using dismembered taxidermy from a nearby New Mexico shop. Anatomically, the Frankenstein-esque creatures appeared otherworldly, revolving on a carousel reminiscent of a slaughterhouse. Nauman thrived at the height of his multimedia manufacturing. In 1989, he married fellow artist Susan Rothenberg, and the couple relocated to a farm in nearby Galisteo, where they still currently reside.

Recent Work By Nauman

Video became Nauman’s primary preoccupation throughout the 1990s and 2000s. Exploring his own communicative power, he systematically tested the contextual relationship between body and surrounding space, curious about time as a relative concept. For example, his 1993 work Feed Me/Anthro-Socio featured a spinning actor screaming “feed me, help me, eat me, hurt me,” incomplete without a viewer’s immersion. Unlike his contemporaries, Nauman’s selected subjects situationally shaped his video installations, not vice versa. In 1999, he was individually awarded a Golden Lion at the 48th Venice Biennale, the highest prize for film submissions. The American Academy Of Arts and Letters inducted him as a member in 2000, and in 2004, he received a Praemium Imperiale. Awarded by the Japan Art Association, the accolade distinguished “artists who have contributed significantly to the development of international arts and culture.” Bruce Nauman had epitomized what it meant to be considered a global figurehead.

Today, he lives a humble life on his New Mexico farm. Few would suspect his unassuming complex to house a studio in a tiny shed, adjoining green pastures for horse grazing. Though his art still plays an important role, Nauman has expanded into other business sectors, even occasionally selling wild stock. He’s nevertheless matured creatively during his time in Galisteo. One of his most recent works, Contrapposto Studies, I Through VII (2016), investigates sound and video by depicting Nauman striking a contrapposto pose. Acting as a doppelganger to his first famous Walk with Contrapposto (1968), the digitally-manipulated media rendered his movements in positive and negative film, forward and backward respectively. Even when faced with the inevitably of aging, Nauman’s focus on corporeality hasn’t changed much over the years. Rather, his grasp on his biological clock has made way for more intimate examinations of his psyche. His future may hold even greater insights.

Bruce Nauman’s Cultural Legacy

Bruce Nauman’s work functions as an eerie societal litmus test. No matter how aggressive, provocative, or plain horrific, the artist continues to expand both his intellectual and physical confines to bewilder, bewitch, and bemoan an international audience. At eighty-one years old, he’s withstood hateful criticism, overwhelming praise, and even near-fatal bowel cancer, none of which have halted his steady perseverance. Spurring deep mental discomfort, his anti-art has loosened public consciousness for better or worse, transporting us vicariously through his creative quest for freedom. Bruce Nauman will proceed to polarize viewers long after his mournful demise.