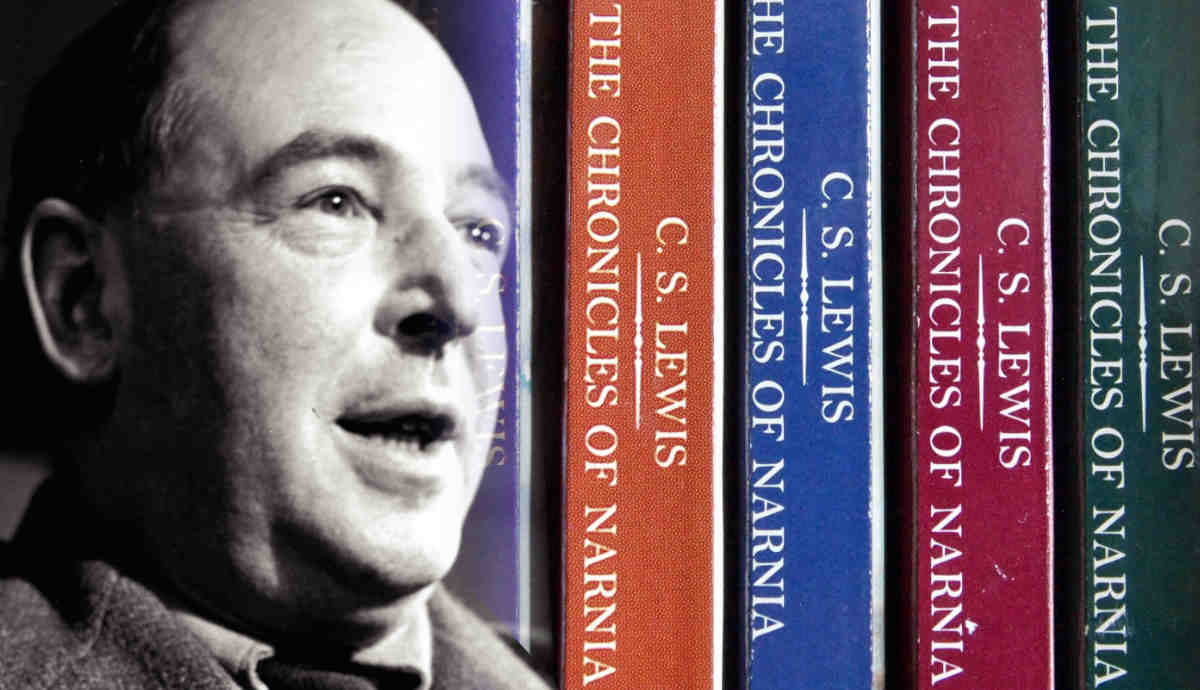

As well as being an Oxford don, C.S. Lewis was also a prolific writer of non-fiction (including works of Christian philosophy and academic literary criticism) and fiction for readers of all ages. It is for his Chronicles of Narnia that he is perhaps best known today. However, here we will take a tour through Lewis’ body of work, exploring some of his best-known books – as well as some that deserve rediscovering…

1. The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe, 1950

To this day, C.S. Lewis is best known and most loved for his children’s fantasy series, The Chronicles of Narnia – and the publication of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe in 1950 marked the beginning of that beloved series of seven books. Though it can be considered the second book in the series in the narrative’s chronology, it remains the best-known Narnia novel.

The novel centers around the exploits of four children (Peter, Susan, Edmund, and Lucy Pevensie) who have been evacuated to a house in the country during the Second World War. Here, Lucy discovers a wardrobe that doubles as a portal to the magical land of Narnia, where (on her third visit) she brings her three siblings. Together, they embark on a quest to save Narnia from the clutches of the evil White Witch and, in doing so, fulfill an ancient prophecy.

Not only is the novel’s main character named after Lucy Barfield (daughter of fellow Inkling Owen Barfield and Lewis’ goddaughter), but it is also dedicated to her. By the time The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe was published, however, she was fifteen years old and, Lewis feared, “already too old for fairy tales,” writing in his dedication: “I wrote this story for you, but when I began it I had not realised that girls grow quicker than books.”

He hoped, nonetheless, that she would enjoy the story when she became “old enough to start reading fairy tales again.” After being hospitalized with Multiple Sclerosis in her later life, she did indeed enjoy having her younger brother Geoffrey (whom her parents had fostered) read The Chronicles of Narnia aloud to her. Likewise, Lucy Barfield’s enjoyment of The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe is shared by readers of all ages around the world.

2. The Problem of Pain, 1940

Published in 1940, The Problem of Pain sees Lewis grapple with the philosophical question of how we can square the existence of an omnipotent, omnibenevolent God with the pain and suffering endured by humans and animals. Though Lewis was a committed Christian by the time he wrote The Problem of Pain, he had been an atheist for many years, meaning he is perhaps ideally suited to tackle this most weighty of subjects.

Beginning with his atheism, he outlines his former pessimistic view of both the state of the world and the likelihood of God’s existence, while in the remainder of the book, he argues that neither pain nor hell are valid reasons for rejecting the belief in the existence of a benevolent, almighty God. That is to say, the existence of suffering does not contradict the existence of God.

In order to argue this position, Lewis questions the meanings we attach to such concepts as happiness and goodness, suggesting that human suffering might, in the end, lead us to greater happiness and to an acceptance of God’s existence. As Lewis himself states, “God whispers to us in our pleasures, speaks in our conscience, but shouts in our pain: it is His megaphone to rouse a deaf world.”

Lewis also accepts the notion that humans have free will, which they can exercise to cause suffering for themselves and others. Though the Fall of Man constitutes the greatest abuse of free will within the Judeo-Christian tradition, Lewis rejects the doctrine of total depravity, according to which every human being is naturally predisposed to sin following original sin unless they are saved by either irresistible or prevenient grace. Eschewing doctrinal cant, The Problem of Pain is an insightful and compassionate meditation on faith and suffering, written by an enquiring and informed mind.

3. The Screwtape Letters, 1942

Originally published in 1942, The Screwtape Letters is dedicated to Lewis’ friend, colleague, and fellow Inkling, J.R.R. Tolkien, who was instrumental in converting Lewis from atheism to Christianity. It is therefore fitting that The Screwtape Letters is a Christian apologetic novel.

Written as an epistolary novel, the demon Screwtape corresponds with his nephew, Wormwood, writing in the capacity of the younger demon’s mentor. Across 31 letters, he advises Wormwood on how best to tempt “the Patient” to sin and stray from God’s teachings. Within this, Screwtape’s letters afford Lewis ample space in which to observe human nature and human morality, covering such topics as war, love, sex, and pride, among many others.

Despite the apparently weighty subject matter and the fact that Lewis claimed that it had not been a fun experience writing The Screwtape Letters, it is also a humorous, satirical novel. Indeed, Lewis includes two epigraphs, quoting both the Catholic Saint Thomas More and the Protestant Martin Luther, both of whom state that the devil cannot stand being mocked. These pronouncements therefore give Lewis a comedic carte blanche in The Screwtape Letters, and the result is a wildly funny and original work of fiction.

And though Lewis claimed not to have exactly enjoyed writing the novel and vowed never to write another “Letter,” he did write a follow-up article entitled “Screwtape Proposes a Toast,” which was published in The Saturday Evening Post in 1959. Here, Lewis takes up a more political stance than he does in The Screwtape Letters, criticizing recent trends and developments within British society and state schools. Aside from his own sequel, The Screwtape Letters has inspired myriad sequels from other writers since its publication.

4. The Great Divorce, 1936

As well as being a writer, Lewis was also a professor of English Literature at Oxford University, and in 1936 he published The Allegory of Love, a seminal study of the allegorical tradition in relation to the treatment of courtly love in Medieval and Renaissance literature. A bona fide expert in allegory, he then went on to write The Great Divorce, a work of Christian allegory about a bus journey from hell to heaven, which was published in 1945. Here, Lewis ponders the existence of heaven and hell (and whether the one can exist without the other), as well as the true spiritual and moral cost of our day-to-day behavior.

The Great Divorce begins in “the grey town,” a drab and dreary city that symbolizes hell or purgatory – depending on how long a character remains there. There is, however, an opportunity for the narrator to board a bus that takes inhabitants of “the grey town” to heaven. The narrator embarks on the journey, during which he and his fellow passengers lose their earthly physical forms and become vaporous and ghost-like as the bus ascends into the clouds.

The ghostly figures of those they knew in life appear and urge them to repent, though most of the passengers choose to return to “the grey town” instead. The narrator, however, journeys on and is met by the author and Christian minister George MacDonald, who becomes his guide (echoing Virgil’s role in Dante’s Divine Comedy). The allegory is then largely explained by MacDonald, and he encourages the narrator to write of his journey and to present it as though it were a dream vision – a genre popular in the Medieval period and one with which Lewis would have been intimately familiar.

5. The Four Loves, 1960

In The Four Loves, published in 1960, Lewis examines love through a Christian, philosophical perspective, distinguishing four categories of love: affection, friendship, eros, and charity. The Four Loves might therefore be considered to have been in keeping with the counter-cultural revolution taking place in the 1960s, though it was based on a series of radio broadcasts Lewis made in 1958, which had sparked controversy due to their treatment of sexual matters.

Having divided love into these categories, Lewis stipulates that “the highest does not stand without the lowest.” The highest, however, is charity, without which, Lewis argues, all other loves can become bitter, twisted – and potentially harmful. Charity, for Lewis, designates the selfless and unconditional love of God.

The Four Loves is a work of philosophy heavily inflected by Lewis’ Christian faith. For a fictional treatment of the same themes explored in The Four Loves, however, Lewis also wrote (in collaboration with his wife, Joy Davidman) Till We Have Faces: A Myth Retold (1956), which is a novelistic reimagining of the myth of Cupid and Psyche, as told by Apuleius in The Golden Ass.

6. A Grief Observed, 1961

Inspired by the loss of his wife Joy Davidman to cancer in 1960, A Grief Observed was published in 1961 under the pseudonym N.W. Clark. Due to the personal nature of the book’s subject matter, Lewis refers to his late wife as “H” (Joy’s first name was Helen, though she seldom used it) throughout the book and chose not to use his own name.

A Grief Observed is a tender, honest, and moving account of one man’s grief and of his struggle to reconcile his faith in God with his loss – returning once again to the issue at the heart of The Problem of Pain. Ultimately, however, Lewis comes to feel gratitude towards God for having allowed him to love and be loved, even if it has caused him such pain.

Lewis, however, died just two years after A Grief Observed was published. In June 1961 (the same year the book was published), he experienced symptoms of nephritis, which graduated to blood poisoning. By 1963, he was diagnosed with end-stage kidney failure, from which he died on November 22nd at his home. As the books mentioned here attest, however, he left behind a rich legacy as a writer of fiction for all ages and of Christian philosophy that endures to this day.