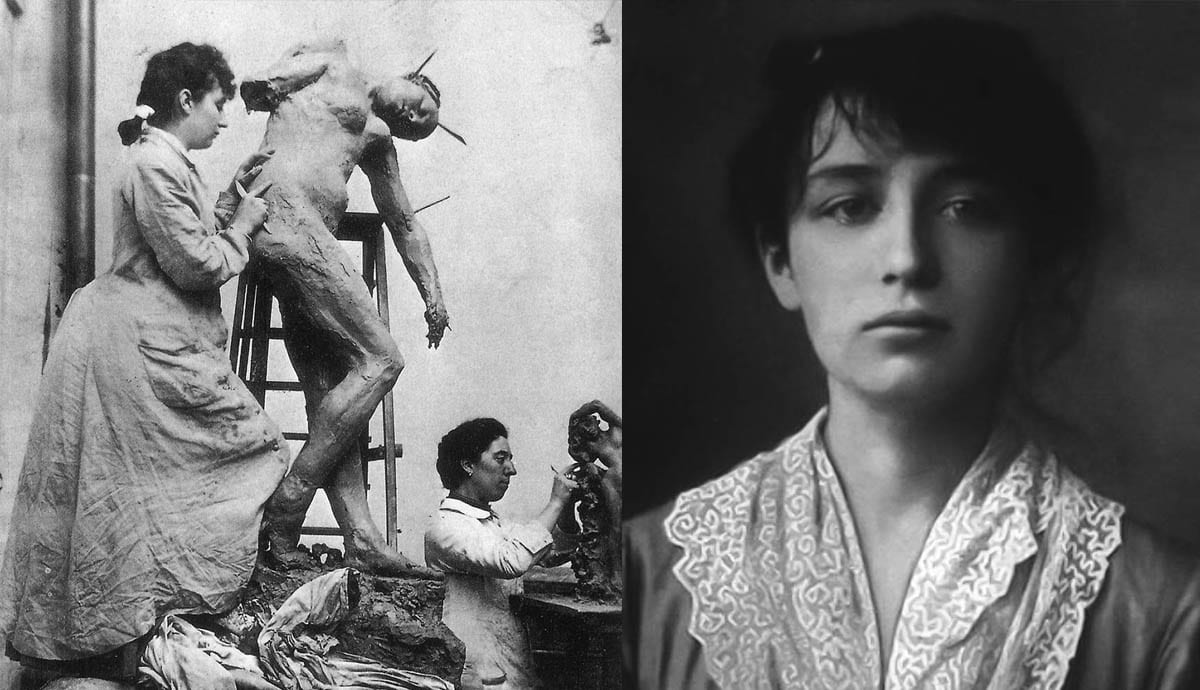

Reflecting on her life as a sculptor at the turn of the century, Camille Claudel lamented “What was the point of working so hard and of being talented, to be rewarded like this?” Indeed, Claudel spent her life in the shadow of her collaborator and lover Auguste Rodin. Born to a middle-class family with more traditional ideas about their daughter’s occupation, stereotypes about women artists followed her from adolescence through adulthood. Nevertheless, she produced a vast body of work that demonstrated not only her artistic brilliance but also her impressive sculptural range and sensitivity towards figural interactions. Today, Camille Claudel is finally receiving the recognition she was owed more than a century ago. Read on to learn more about why this trailblazing, tragic female artist is so much more than a muse.

Camille Claudel As A Defiant Daughter

Claudel was born on December 8, 1864 in Fère-en-Tardenois in northern France. The oldest of three children, Camille’s precocious artistic talent endeared her to her father, Louis-Prosper Claudel. In 1876, the family relocated to Nogent-sur-Seine; it was here that Louis-Prosper introduced his daughter to Alfred Boucher, a local sculptor who had recently won second price for the prestigious Prix de Rome scholarship. Impressed by the young girl’s ability, Boucher became her first mentor.

By her mid-teens, Camille’s growing interest in sculpture had created a rift between the young artist and her mother. Women artists were still a unique breed in the late nineteenth century, and Louise Anthanaïse Claudel implored her daughter to abandon her craft in favor of marriage. What support she did not receive from her mother, however, Camille surely found in her brother, Paul Claudel. Born four years apart, the siblings shared an intense intellectual bond that continued into their adult years. Much of Claudel earliest works– including sketches, studies, and clay busts– are likenesses of Paul.

At 17, She Moves To Paris

In 1881, Madame Claudel and her children moved to 135 Boulevard Montparnasse, Paris. Because the École des Beaux Arts did not admit women, Camille took classes at Académie Colarossi and shared a sculpture studio at 177 Rue Notre-Dame des Champs with other young women. Alfred Boucher, Claudel’s childhood teacher, visited the pupils once a week and critiqued their work. Aside from the bust Paul Claudel a Treize Ans, other work from this period includes a bust titled Old Helen; Claudel’s naturalistic style earned her the compliments of Paul Dubois, director of the École des Beaux-Arts.

Her Talent Caught The Eye Of Auguste Rodin

A major turning point in Claudel’s professional and personal life occurred in the autumn of 1882, when Alfred Boucher left Paris for Italy and asked his friend, the renowned sculptor Auguste Rodin, to take over supervising Claudel’s studio. Rodin was deeply moved by Claudel’s work and soon employed her as an apprentice in his studio. As Rodin’s only female student, Claudel quickly proved the depth of her talent through contributions to some of Rodin’s most monumental works, including the hands and feet of several figures in The Gates of Hell. Under her famous teacher’s tutelage, Camille also refined her grasp on profiling and the importance of expression and fragmentation.

Camille Claudel and Auguste Rodin: A Passionate Love Affair

Claudel and Rodin shared a connection beyond sculpture, and by 1882 the pair was engaged in a tempestuous love affair. While most present-day portrayals emphasize the taboo elements of the artists’ tryst– Rodin was not only 24 years Claudel’s senior, but he was also all-but-married to his lifelong partner, Rose Beuret–their relationship was grounded in mutual respect for each other’s artistic genius. Rodin, in particular, was infatuated with Claudel’s style and encouraged her to exhibit and sell her works. He also used Claudel as a model for both individual portraits and anatomical elements on larger works, such as La Pensée and The Kiss. Claudel also used Rodin’s likeness, most notably in Portrait d’Auguste Rodin.

More Than A Muse

Despite the influence of Rodin’s training, Camille Claudel’s artistry is entirely her own. In an analysis of Claudel’s work, scholar Angela Ryan draws attention to her affinity for the “unified mind-body subject” that diverged from the phallocentric body language of her contemporaries; in her sculptures, the women are subjects as opposed to sexual objects. In the monumental Sakountala (1888), also known as Vertume et Pomone, Claudel depicts the enlaced bodies of a famous couple from Hindu myth with an eye toward mutual desire and sensuality. In her hands, the line between masculine and feminine blurs into a single celebration of corporeal spirituality.

Another example of Claudel’s work is Les Causeuses (1893). Cast in bronze in 1893, the miniaturized work depicts women huddled in a group, their bodies inclined as if engaged in conversation. While the uniform scale and unique details of each figure are a testament to Claudel’s skill, the piece is also a singular representation of human communication in a nonpolarized, nongendered space. The contrast between the diminutive size of Les Causeuses and the larger-than-life figures in Sakountala also speaks to Claudel’s range as a sculptor and contradicts the prevailing idea that women’s art was purely decorative.

Immortalizing Heartbreak

Ten years after their first meeting, Claudel and Rodin’s romantic relationship ended in 1892. They remained on good terms professionally, however, and in 1895 Rodin supported Claudel’s first commission from the French state. The resulting sculpture, L’Âge mûr (1884-1900), comprises three nude figures in an apparent love triangle: on the left, an older man is drawn into the embrace of a crone-like woman, while on the right a younger woman kneels with her arms outstretched, as if imploring the man to stay with her. This hesitation at the crux of destiny is considered by many to represent the breakdown of Claudel and Rodin’s relationship, specifically Rodin’s refusal to leave Rose Beuret.

The plaster version of L’Âge mûr was exhibited in June 1899 at the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts. The work’s public debut was the death knell of Claudel and Rodin’s working relationship: Shocked and offended by the piece, Rodin completely severed his ties with his former lover. Claudel’s state commission was subsequently revoked; although there is not definitive proof, it is possible that Rodin pressured the ministry of fine arts to end its collaboration with Claudel.

Fighting For Recognition

Although Claudel continued to be productive through the first several years of the 20th century, the loss of Rodin’s public endorsement meant that she was more vulnerable to the sexism of the art establishment. She struggled to find support because her work was deemed overly sensual– ecstasy, after all, was considered male territory. The aforementioned Sakountala, for example, was briefly exhibited at the Chateauroux Museum, only to be returned after locals complained about the female artist’s portrayal of a nude, embracing couple. In 1902, she completed her only surviving large marble sculpture, Perseus and the Gorgon. As if alluding to her personal woes, Claudel gave the ill-fated Gorgon her own facial features.

Plagued by financial trouble and rejection by the Parisian art milieu, Claudel’s behavior grew increasingly erratic. By 1906, she lived in squalor, wandering the streets in beggars’ clothes and drinking excessively. Paranoid that Rodin was stalking her in order to plagiarize her work, Claudel destroyed most of her oeuvre, leaving only about 90 examples of her work untouched. By 1911, she had boarded herself into her studio and lived as a recluse.

A Tragic Ending

Louis-Prosper Claudel died on March 3, 1913. The loss of her most consistent familial supporter signaled the final breakdown of Claudel’s career: Within months, Louise and Paul Claudel forcibly confined 48-year-old Camille to an asylum, first in the Val-de-Marne and later in Montdevergues. From this point onward, she declined offers of art materials and refused to even touch clay.

After the end of World War I, Claudel’s physicians recommended her release. Her brother and mother, however, insisted that she remain confined. The next three decades of Claudel’s life were plagued by isolation and loneliness; her brother, once her close confidant, only visited her a handful of times, and her mother never saw her again. Letters to her few remaining acquaintances speak to her melancholy during this time: “I live in a world so curious, so strange,” she wrote. “Of the dream that was my life, this is the nightmare.”

Camille Claudel died at Montdevergues on October 19, 1943. She was 78 years old. Her remains were interred in an unmarked communal grave on the hospital grounds, where they remain to this day.

Camille Claudel’s Legacy

For several decades after her death, Camille Claudel’s memory languished in Rodin’s shadow. Prior to his death in 1914, Auguste Rodin approved plans for a Camille Claudel room in his museum, but they were not executed until 1952, when Paul Claudel donated four of his sister’s works to the Musée Rodin. Included in the donation was the plaster version of L’Âge mûr, the very sculpture that caused the final rupture in Claudel and Rodin’s relationship. Almost seventy-five years after her death, Claudel received her own monument in the form of Musée Camille Claudel, which opened in March 2017 in Nogent-sur-Seine. The museum, which incorporates Claudel’s adolescent home, features about 40 of Claudel’s own works, as well as pieces from her contemporaries and mentors. In this space, Camille Claudel’s unique genius is finally celebrated in a way that social custom and gender norms prevented during her lifetime.

Auctioned Pieces by Camille Claudel

La Valse (Deuxième Version) by Camille Claudel, 1905

Price Realized: 1,865,000 USD

Auction House: Sotheby’s

La profonde pensée by Camille Claudel, 1898-1905

Price Realized: 386,500 GBP

Auction House: Christie’s

L’Abandon by Camille Claudel, 1886-1905

Price Realized: 1,071,650 GBP

Auction House: Christie’s