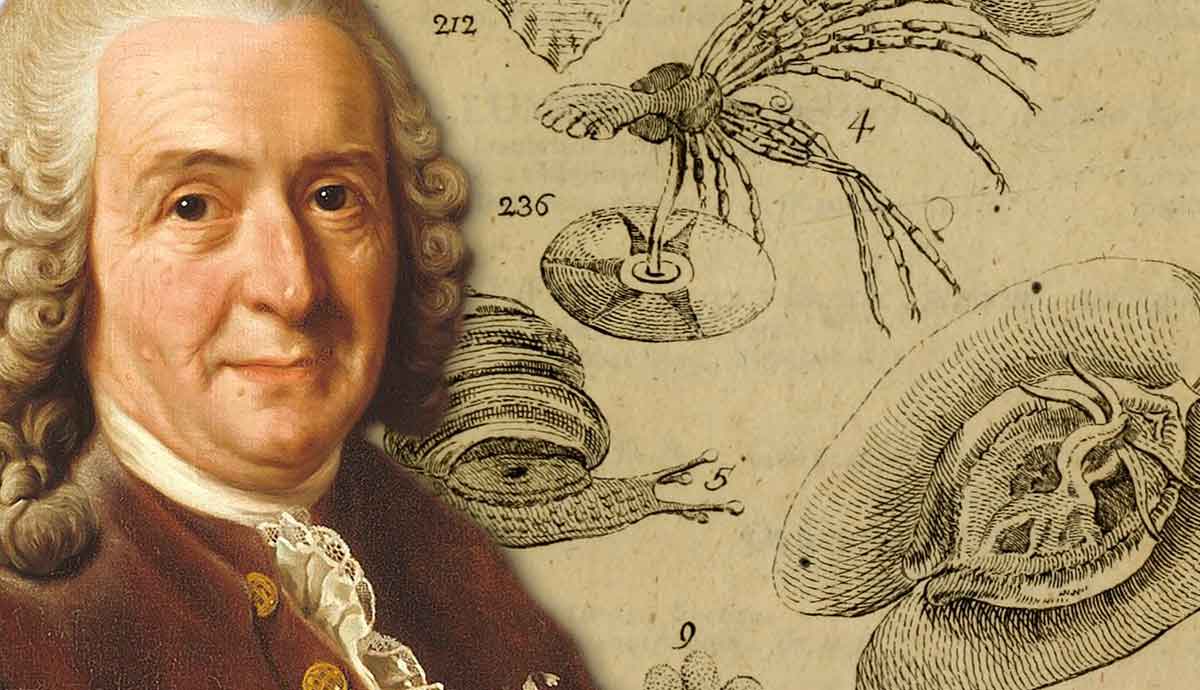

The Swedish naturalist Carl Linné (1707-1778), better known by his Latinized name Carl Linnaeus, and later knighted as Carl von Linné, is the undisputed father of modern taxonomy — the science of identifying, naming, and classifying organisms. His seminal work Systema Naturae (1735) outlined his ideas about the hierarchical classification of the natural world into the animal, plant, and mineral kingdoms. His Species Plantarum (1753), on the other hand, is the book that taught botanists how to name plants. However, Linnaeus’ work on the classification of man also formed a critical starting point for the emergence of modern scientific racism. His contribution to our understanding of the natural world is immense, but not without controversy.

Carl Linnaeus: Early Life and Education

Carl Linné was born in 1707 in Råshult, a small village nestled in the province of Småland, southern Sweden. The son of a county parson, albeit one with an interest in botany, Linné developed a liking for plants at an early age. He spent much time in the family garden with his father, was given his own patch of the garden to grow plants, and began to develop prodigious botanical knowledge. Although he grew up in an impoverished region of Sweden he managed to gain a place at university.

Linnaeus went to a gymnasium (secondary school) and then, at age 21, enrolled at Lund University where he was tutored in Botany and gained access to the library of Professor Killian Stobaeus. He subsequently went on to study medicine and botany at Uppsala University. At both universities, Linnaeus successfully sought patronage from important professors — gaining access to their libraries in the process. Rather than attend lectures, he was largely self-taught and privately tutored — often for free.

The young Carl Linnaeus demonstrated prodigious knowledge in botany and a fine ability to develop situations and opportunities to his advantage. He was a bright and capable student, with an interest in botany close to that of many of his professors. Before he was even awarded his degree at Uppsala, as a second-year student he began to give lectures on botany and he was tasked with instructing students in the botanical gardens.

Following the academic norms of the era, Linnaeus ventured for a time to the Netherlands for further study (1735-1738). In 1735, he was awarded a doctorate in medicine from the Guelders Academy in the small Dutch town of Hardwijk. Yet despite his medical credentials Linnaeus’s passion—and talent—was for natural history.

Following his sojourn in the Netherlands, he practiced as a physician in Stockholm between 1738 and 1741. Subsequently, he returned to Uppsala University, where he became Professor of Medicine and Botany until his death in 1778.

Linné Goes to Lapland

Early modern Swedish Lapland emerged as a captivating Arctic world, characterized by vast stretches of glistening tundra, illuminated by the midnight sun. Towering mountain peaks punctuate the horizon, while dense forests of Pine, Spruce, and Birch stretch as far as the eye can see. The landscape is studded with giant lakes and powerful rivers flowing towards the Gulf of Bothnia, the northernmost reach of the Baltic Sea.

Throughout its history, Lapland has been inhabited by the Sami people, Europe’s sole indigenous group, whom the Swedes called “Lapps.” Lapland has long been of interest to Scandinavian Swedes. However, unlike Sweden’s southern and eastern expansions won by military means after 1611, northern expansion was undertaken under the auspices of the church. By the beginning of the 17th century, Lutheranism was effectively integrating Lapland and its indigenous inhabitants into the Swedish realm. The 18th century brought both romantic fascination and scientific inquiry to Lapland.

In 1732, Carl Linnaeus set off for Lapland after receiving a grant from the Royal Society of Sciences in Uppsala. His journey marked one of the earliest scholarly ventures into the far north. Over six months he covered over 2000 kilometers (1242 miles) on horseback and on foot. Linnaeus meticulously documented close to 100 previously unknown species of plant. His findings were published in his now-famous Flora Lapponica (1732).

However, plants were not the sole focus of the book. Flora Lapponica was rich with illustrations of plants but also laden with romanticized descriptions of the Sami people, whom Linné deemed of great anthropological interest. The Sami were idealized as “noble savages” of the wilderness, unspoiled by the advance of civilization. As Sweden moved further toward the embrace of the new scientific age, Linnaeus’s harmful descriptions became instrumental in shaping racial stereotypes of the Sami for centuries to come.

Systema Naturae

Carl Linnaeus revolutionized the field of taxonomy with his seminal work, Systema Naturae (1735), published in Latin, the scientific lingua franca of the day, Linné’s work proved so popular and influential that it was expanded into several further editions.

At the core of Systema Naturae is the systematic arrangement of the natural world into three “kingdoms” of animals, vegetables, and minerals — establishing a system of hierarchical classification applicable to both organic and inorganic matter. In the all-important 10th edition, the three kingdoms of the “empire of nature” were further subdivided into classes, orders, genera, and species — with each species distinguished by a unique binomial.

For instance, Linnaeus categorized human beings (classified as animals) as mammals, in the order of primates, of the genus homo, and assigned them the binomial Homo Sapiens. The use of binomials in Linnaean taxonomy—known today as binomial nomenclature—was a major innovation. Linnaeus insisted on brevity and descriptive precision: the first part lists the genus and the second succinctly characterizes the species and how it is differentiated from others. In the case of Homo Sapiens, the Latin sapiens means “to be capable of discerning.”

In the first nine editions of Systema Naturae Linnaeus classified the human species into four varieties: Europaeus albus (European white), Americanus rubescens (American reddish); Asiaticus fuscus (Asian tawny), and Africanus niger (African black). However, in the 10th edition, he added several more pages of detail, expanding on these categories with detailed descriptions of skin color, bodily posture, and “medical temperament” (drawing in Humoral theory), physical traits, behavior, manner of clothing, and form of government.

Linnaeus’s hierarchical system placed Black people at the bottom and white Europeans at the top. Europeans were described positively while native Americans, Asians, and especially Black people were consistently associated with negative moral and physical attributes.

Species Plantarum

Species Plantarum (1753) or Species of Plants marked a pivotal moment as the first botanical work to consistently and systematically apply binomial nomenclature to the naming of plants. Published five years before the 10th edition of Systema Naturae, it represented the earliest scholarly effort to apply the binomial system to a large group of organisms.

The first edition of Species Plantarum meticulously cataloged and described 5,940 plants, reflecting the entirety of Linnaeus’s botanical knowledge at the time. Published as a two-volume work, Species Plantarum stands as the cornerstone of modern botanic nomenclature. Before Species Plantarum, plants were often given long, unwieldy Latin names, assigned at random by different observers. Linnaeus’s solution, designating a plant by a genus name and a terse description of the species, was a revelation.

When it comes to plants Linnaeus is perhaps most famous for his production of a general key for the classification of plants: the systema sexuale (sexual system). Talk of the sex of plants was a controversial topic in Linnaeus’s time — he was slandered as a “botanical pornographer” among other things. However, building on the proven existence of male and female reproductive organs in plants, Linnaeus chose to classify and order plants based on the number of their reproductive organs: stamens (male) and pistils (female). Despite the controversy that it generated, the sexual system proved to be very useful.

Taken together, Linnaeus’s innovations standardized and formalized plant classification, fostering enhanced communication and possibilities for collaboration among botanists and scientists. Moreover, they democratized the joys of botanical exploration and discovery, making it accessible to a wider public. Species Plantarum advanced the field of botanical science but also had a profound impact on ecology, agriculture, and conservation.

Carl Linnaeus’s Legacy

In one of his several autobiographies, Carl Linnaeus unabashedly listed his achievements: “No one has been a greater Botanicus or Zoologist. No one has written more books, more correctly, more methodically, from his own experience. No one has more completely changed a whole science and initiated a new epoch. No one has become more of a household name throughout the world…”

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe equated Linnaeus’s influence upon him with that of Shakespeare and Spinoza. Jean Jacques Rousseau once claimed that he knew of no greater man on earth than Linnaeus. Yet the title that Linnaeus truly coveted—and wanted to be engraved on his tombstone—was princeps botanicorum (“prince of botanists”).

Before Linnaeus, publications on the natural world were confined to bestiaries—medieval compendiums of “beasts” listed in alphabetical order—and descriptive catalogs of herbs and local fauna and flora. While the English naturalist John Ray (1627-1705) was the first to take a major step toward the production of modern taxonomy, Linnaeus’s approach was revolutionary.

Rather than simply going out into the natural world and observing and describing things, Linnaeus developed a practical cataloging system of the natural world that was both hierarchical and relational. His most renowned innovation—binomial nomenclature, the labeling of all known plants and animals with two-part Latin names—continues to structure human knowledge of the natural world.

Yet Linnaeus’s legacy is a complex tapestry, as controversial as it is awe-inspiring. His hierarchical classification of human beings laid the groundwork for the birth of scientific racism. As a central, highly influential figure in natural science, Linnaeus’s portrayal of Africans as “unemotional, sly and lazy” as opposed to hierarchically superior “wise, inventive” white Europeans, laid “scientific” foundations for European imperialism and racial stereotypes that continue to this day.