The catacombs of Alexandria, also known as Kom el-Shoqafa or “mound of shards’’ in Arabic, is one of the seven wonders of the medieval world. The structure was re-discovered in September 1900, when a donkey treading about in Alexandria’s outskirts found itself on unstable ground. Unable to regain its balance, the unfortunate explorer plummeted into the access shaft of the ancient tomb.

Unearthing the Catacombs of Kom El Shoqafa, Alexandria

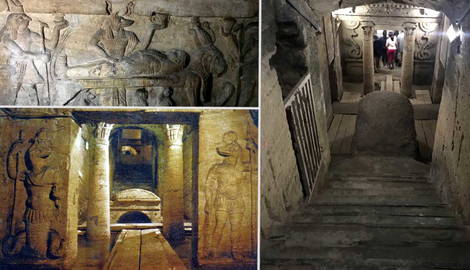

Soon after the discovery of the site, a team of German archaeologists started excavating. In the years that followed, they laid bare a spiral staircase cut out around a circular shaft. At the bottom, they found an entrance leading to a domed circular room, known as a rotunda.

In the rotunda, the archaeologists found several portrait statues. One of them depicted a priest of the Graeco-Egyptian deity Serapis. The cult of Serapis had been promoted by Ptolemy, one of Alexander the Great’s generals and later the ruler of Egypt. He did so in an attempt to unify the Greeks and Egyptians in his realm. The god is often depicted as Greek in physical appearance yet decorated with Egyptian ornaments. Derived from the worship of the Egyptian gods Osiris and Apis, Serapis also has attributes from other deities. For example, he was ascribed powers relating to the Greek god of the underworld Hades. This statue was one of the first indications of the site’s multicultural nature.

Moving from the rotunda deeper into the tomb, the archaeologists encountered a Roman-style dining hall. After the burial and on commemorative days, the relatives and friends of the deceased would visit this room. Bringing plates and jars back up to the surface was likely seen as bad practice. As such, visitors purposely broke the containers of the food and wine they brought, leaving pieces of terracotta jars and plates on the floor. When the archaeologists first entered the room, they found it littered with fragments of pottery. Soon thereafter, the catacombs came to be known as Kom el-Shoqafa or “mound of shards’’.

The Hall of Caracalla (Nebengrab)

The rotunda connects to a room with an altar situated in the center. Carved into the walls are places to fit sarcophagi. The central wall of the chamber contains one Greek scene, Hades kidnapping the Greek goddess Persephone, and an Egyptian one, Anubis mummifying a corpse.

On the ground of the chamber, the archaeologists found large numbers of human and horse bones. They theorized the remains belonged to the victims of a mass slaughter orchestrated by the Roman emperor Caracalla in 215 CE.

Eight years before the massacre, the local Roman garrison had been sent away to guard the empire’s northern borders. On multiple occasions, the citizens of Alexandria used the weakened rule of law to protest against Caracalla’s reign. Furthermore, the Roman emperor had received word that the Alexandrians made jokes about him murdering his brother and co-ruler Geta, whom he had killed in front of their mother. One of the ancient sources of the slaughter mentions that Caracalla ordered Alexandria’s young men to gather at a designated square under the pretense of an inspection for military service. Once many Alexandrians had assembled, Caracalla’s soldiers surrounded them and attacked. Another version of the story tells of Caracalla inviting prominent Alexandrian citizens to a banquet. Once they had begun eating, Roman soldiers appeared from behind and killed them. Afterward, the emperor sent his men into the streets to attack anyone they encountered.

The archaeologists theorized that the bones found on the ground of the Hall of Caracalla belonged to victims of the massacre. The unfortunate Alexandrians had sought refuge in the catacombs but were caught and slaughtered. However, the connection between the massacre of Caracalla and the tomb remains dubious, and for this reason, the Hall of Caracalla is also known as Nebengrab for being next to the main tomb.

As for the horse bones, a physician examined them and identified them as having belonged to race horses. Possibly, the winners of racing events were given the honor of being buried in the tomb.

Entering the Main Tomb

From the rotunda, a set of stairs leads down to an entrance flanked by two pillars. A winged solar disc situated between two falcons symbolizing the Egyptian god Horus is depicted above the passage. The facade also bears inscriptions of two cobras with shields placed above them. The imagery was likely added to ward off graverobbers and other ill-intentioned visitors.

Walking through the entrance into the principal tomb, the first thing the archaeologists would have noticed were two statues located in niches on either side of the doorway. One depicts a man wearing Egyptian-style clothing, his hair portrayed in the roman tradition of the 1st and 2nd centuries CE. The other statue depicts a woman, her hair also worn in the Roman style. However, she bears no clothes, as is common in Greek statues. It is speculated that the statues depict the tomb’s main owners.

The walls alongside the two statues bear inscriptions of bearded serpents representing Agathodaemon, a Greek spirit of wineries, grain, good luck, and wisdom. On their heads, the snakes wear the pharaonic double crowns of Upper and Lower Egypt. Carved into the stone above them, are shields bearing the head of the gorgon Medusa staring down visitors with her petrifying gaze.

The Main Burial Tomb

Entering the main burial chamber, the archaeologist encountered three large sarcophagi. Each is decorated in Roman style with garlands, the heads of gorgons, and an ox skull. Three relief panels are carved into the walls above the sarcophagi.

The central panel depicts Osiris, the Egyptian god of the afterlife, dead, and resurrection, lying down on a table. He is being mummified by Anubis, the god of death, mummification, and the underworld. At the sides of the bed, the gods Thoth and Horus are assisting Anubis with the funerary rite.

The two lateral panels show the Egyptian bull god Apis receiving gifts from a pharaoh standing beside him. A goddess, possibly Isis or Maat, is watching Apis and the pharaoh. She holds the feather of truth, used to determine if the souls of the deceased are worthy of the afterlife.

On the interior side of the doorway, two reliefs of Anubis are guarding the entrance. Both are dressed as roman legionaries, wearing a spear, shield, and breastplate.

Catacombs of Kom El Shoqafa, Alexandria: Construction & Use

The catacombs date back to the second century CE. The structure reaches a depth of over 100 feet and was built using ancient rock-cutting technology. The entirety of the catacombs was carved out of bedrock in a lengthy and labor-intensive process.

For centuries after its construction, the catacombs continued to be used. The dead were lowered into the tomb with ropes through the vertical shaft located next to the stairs and then moved deeper underground. The catacombs most likely started out as a private complex for the man and woman whose statues stand in the niches in the principal tomb. Later and until the 4th century CE, the structure became a public cemetery. In its entirety, the complex could accommodate up to 300 corpses.

People visited the location for burials and commemorative feasts. Priests performed offerings and rituals in the catacombs of Kom El Shoqafa. Their activities likely included mummification, as the practice is depicted in the main burial chamber.

Eventually, the catacombs fell out of use. The entrance was covered by the earth, and the people of Alexandria forgot of its existence.