Overlooking the Konya Plain in Southern Anatolia, Turkey, is one of the most fascinating places in all of human history. It is here that human beings in the area abandoned a nomadic lifestyle and began building one of the oldest cities on record. Today, the site is known as Çatalhöyük.

Built on an artificial hill called a tell, Çatalhöyük was inhabited for around 1,400 years. Successive generations rebuilt on top of old buildings, eventually culminating in 18 layers of settlement.

Digging so far into the past is a difficult but wondrous process for the archeologists involved, who, through their work, have helped to bring us the story of the mysterious people who lived there.

Discovery, Excavation, & Scandal

Eighty-seven miles (140 kilometers) from the twin-coned volcano of Mount Hasan and standing 66 feet (20 meters) above the Konya plain is the mound on which Çatalhöyük was built. With a panoramic view of the surrounding area of wide open plains, Çatalhöyük was ideally located.

The site was first excavated in 1958 by English archeologist James Mellaart and his team, who returned in 1961 and worked on the site until 1965. The excavations revealed that the site had 18 layers of inhabitation of advanced culture during the Neolithic and late Neolithic periods. The bottom layer, being the oldest, was dated to around 7100 BCE, while the top layer was dated to about 5600 BCE.

Mellaart was later implicated in the Dorak Affair, in which he published drawings of Bronze Age artifacts from shallow graves in the city of Dorak, near the ancient site of Troy. These artifacts went missing, and Mellaart was accused of smuggling the items from Turkey. Whatever the truth, Mellaart became persona non grata and was only allowed to excavate in 1965 as an assistant. Nevertheless, Mellaart still gets the bulk of the credit for the initial excavation of the site.

It wasn’t until 1993 that excavation at the site resumed. The archeologist in charge, Ian Hodder, was a student of Mellaart and worked on the site until 2018 when his excavations finished. In the first year alone, Hodder and his team unearthed over 20,000 items.

Digital collection methods and radiocarbon dating have contributed greatly to recent excavations and helped archeologists create new pictures of life in Çatalhöyük. New excavations are planned for the future.

The Structures of Çatalhöyük

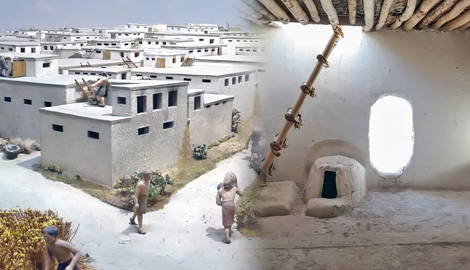

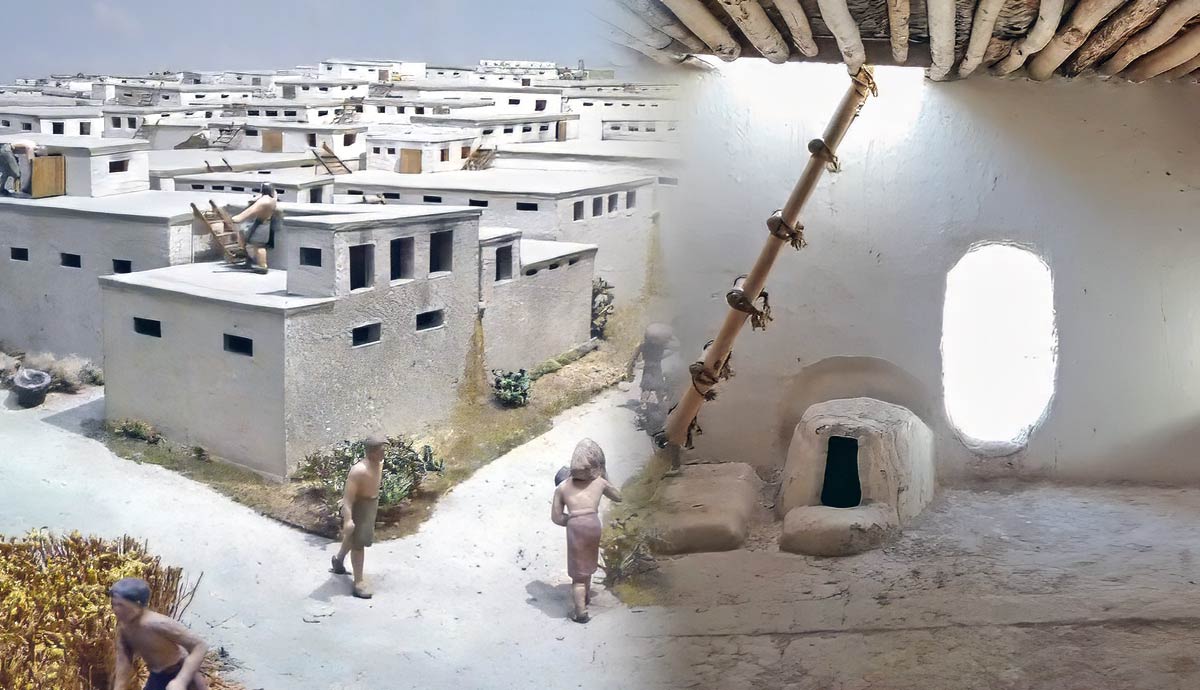

Çatalhöyük was comprised completely of residential mudbrick buildings. There were no warehouses or public buildings. The houses were crammed tightly together, sharing walls, so much so that the city had no streets, and most buildings had no access at ground level. Instead, buildings were accessed via ladders to doors on the roofs. These roof openings also served as the only form of ventilation in many of the houses. Therefore, the city roofs served as the streets.

Virtually every house discovered at Çatalhöyük was found to be decorated with ochre murals of geometric and figurative painting. These designs, in some cases, were refreshed regularly. Many of the paintings also feature wild animals and hunting scenes involving aurochs and stags.

This indicates that although sedentary, the people of Çatalhöyük still practiced hunting as an important part of acquiring food. A common feature found in many homes was bull horns used as decorative and functional items. They were turned into seating in communal areas with the horns pointing forward. Other items from animals, such as teeth and beaks, were used to decorate the walls and often plastered over.

The houses usually had several rooms, including two main rooms connected to ancillary rooms. Raised platforms created a surface on which activities such as cooking could be done. The walls were plastered, and each house had a cooking hearth or an oven.

The houses were kept extremely clean, and garbage was disposed of in areas outside the settlement. In later years, large communal hearths were also built on some of the roofs and served as meeting places for the inhabitants of Çatalhöyük.

Throughout the centuries, the population certainly fluctuated. The biggest population estimate is around 10,000 people, but 6,000 to 7,000 is probably more likely for most of the eras through which the city survived.

The Dead & Buried

The people of Çatalhöyük had a close relationship with their dead. Bodies were buried in a flexed position and interred underneath the house’s floor. Before burial, bodies were often placed in baskets or tightly bound in reed mats. Evidence suggested that many bodies were laid out in the open air for a time before being interred, as suggested by disarticulated bones gathered up and buried.

What is interesting about Çatalhöyük burials is that, in many cases, the bodies were disturbed after burial and the skulls removed. Some of the skulls were found far away from the rest of the skeleton and were decorated with plaster and painted with ochre to recreate the faces. They were likely used in religious ceremonies. Many of the skeletons were also found to be painted.

Religion, Matriarchy, & Patriarchy?

Although no temples or dedicated sites of worship are evident in Çatalhöyük, it is clear that the people who lived there had a strong sense of the divine. This is indicated through the ceremonial use of skulls and the many figurines that have been discovered at the site. To date, 2,000 figurines have been discovered, and while most of them depict animals, it is the figurines of the females that hint at some sort of veneration of a mother goddess. This assertion was put forward by Mellaart, who suggested that Çatalhöyük had a matriarchal society. Hodder, however, argues that there is little evidence for a matriarchal or patriarchal society.

The original excavations uncovered only 10% of the figurines found to date. While the archeologists may have focused on the female figurines, the total percentage of female-representative figurines found only comprises 5% of what has been discovered when the items of the modern excavations are added. The vast majority of the figurines are actually representative of animals. The figurines were carved and molded from clay, marble, limestone, schist, calcite, alabaster, and basalt.

Further evidence that the society was neither matriarchal nor patriarchal is the religious position occupied by the skulls that were removed from the bodies. Both male and female skulls have been found in equal numbers, occupying equal positions.

One instance of the belief in a female deity (probably one of many deities) is the idea of a deity that protected grain crops and represented agricultural needs. This is suggested by the placement of a particular design of female figurines, a few of which have been found in Çatalhöyük’s grain bins.

Besides this focus on debating the existence of a Mother Goddess religion, it has also been suggested that since the people of Çatalhöyük were still hunter-gatherers, despite their sedentary living conditions, their spiritual beliefs would have been connected to the animal world. This is certainly supported by the sheer number of animal figurines that have been discovered.

Economy

The people of Çatalhöyük represented an intermediary period between hunter-gathering and agriculture. Their knowledge of farming had no prior precedent from which to learn. Nevertheless, their skills developed rapidly. Wheat and barley were the main crops, while pistachios, almonds, peas, and various fruits were grown. Sheep were domesticated, and attempts were made to domesticate cattle. Most tools were of stone and obsidian, as metalwork had not been invented. Along with these tools, pottery played an important part in a large industry.

As Hodder suggests, Çatalhöyük suggests a strong egalitarian culture, and not just between men and women. There is no evidence of any sort of societal hierarchy. The houses are all similarly sized, and evidence suggests everybody received the same nutrition. It has been suggested that Çatalhöyük represents an early anarcho-communist society with a strong ethic of equality among its citizens. It was not, however, a perfect society for its entire existence. Studies suggest equality broke down as intergenerational wealth created divisions. There seem to have been efforts to amend these inequalities.

Cramped living conditions and proximity to sheep also brought with it the new dynamic of diseases that could be spread easily, creating problems within society. Violence was not unknown, and skulls have been found with significant head wounds.

The change to a mainly grain-based diet also brought severe dental problems.

What caused the eventual abandonment of the city is unknown. As early farmers, it may have been due to some form of environmental change that made sustaining a population through agriculture untenable.

The people of Çatalhöyük were constantly forced to adapt. Human civilization was a new idea, and they had no precursors. What they were doing was a new experiment in human survival.

Despite their problems, what they created was a marvel given the context, and what they left behind is a testament to the ingenuity and creativity of the human species.