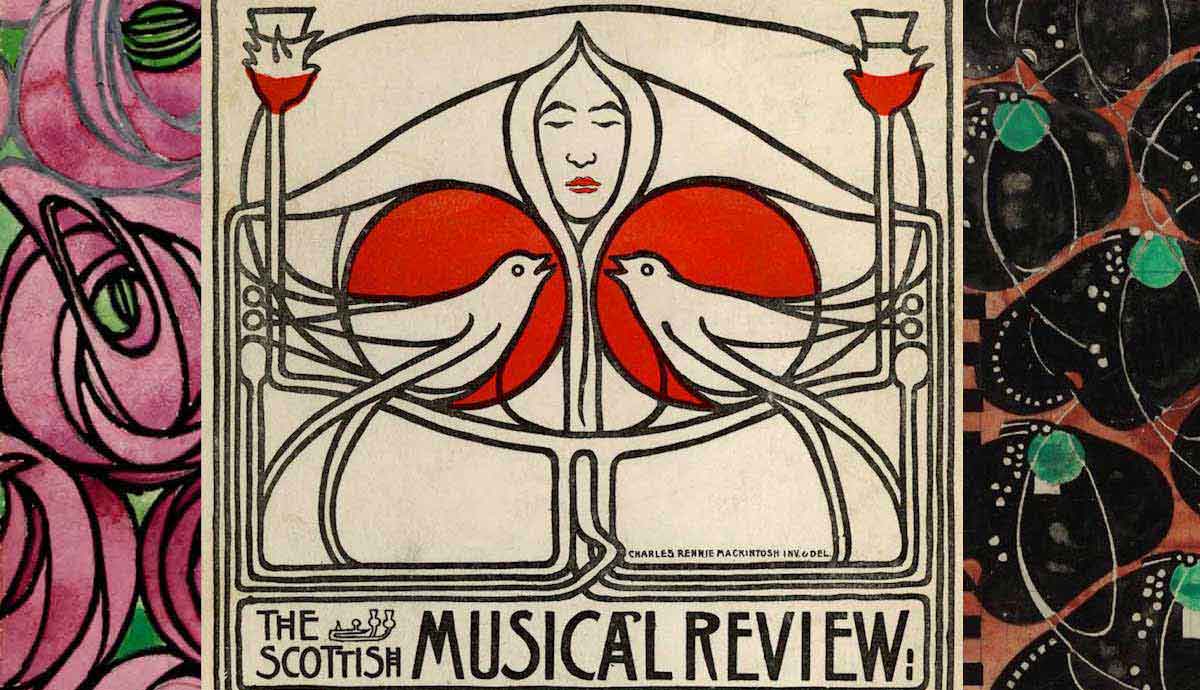

“Life is the leaves which shape and nourish a plant,” said Charles Rennie Mackintosh, “but art is the flower which embodies its meaning.” Around the turn of the century, Mackintosh’s trailblazing architectural aesthetic bloomed across his hometown of Glasgow, Scotland. These buildings and their furnishings helped lay the foundation for the Glasgow School movement, which became the United Kingdom’s most notable contribution to international Art Nouveau.

Get to know Charles Rennie Mackintosh through the lens of his most interesting and innovative designs, from the famous Mackintosh rose to his lesser-known, late-career watercolors.

1. Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Iconic Rose

If you ever come across a turn-of-the-century cabinet, a swatch of fabric, or even a modern-day museum souvenir featuring a simplified rose motif—it was probably designed by Charles Rennie Mackintosh. The Mackintosh rose is a rounded aesthetic distortion almost beyond recognition. Yet today it remains the most memorable, and the most ubiquitous, of Mackintosh’s many designs. Indeed, of all his work, the Mackintosh rose especially epitomizes what made Mackintosh a groundbreaking designer. The Mackintosh rose successfully combines seemingly disparate aesthetics into one harmonious whole. Geometric angles complement organic curves, and heavy industrial materials interplay with delicate pastel colors—and the resulting motif is stunningly simple and versatile.

Pictured above, this textile design is one of Mackintosh’s most mature iterations of the rose motif. When you observe the composition closely, you notice that every rose, albeit simple, is subtly different from the rest. This emphasizes the creative interplay between the modern simplicity of geometry and the wild, organic nature of a real-life rosebush.

One of the reasons why the Mackintosh rose resonates is that it can stand alone as a piece of art and add character to a more complex total design. The second example pictured is an illustration that Mackintosh designed to decorate the front of a wooden cabinet. The subject is a woman holding a rose. But instead of creating a representational composition, Charles Rennie Mackintosh viewed the subject as an opportunity to push the aesthetic boundaries of line, form, and scale.

2. The Glasgow School of Art Library

As an emerging young architect, Charles Rennie Mackintosh entered and won a competition to design a new building for his alma mater. His daringly modern design for the new Glasgow School of Art building became his first and most significant architectural commission.

Mackintosh unified a staggering variety of influences, from traditional Japanese courtyards to Gothic revivalism to the natural world itself—all realized using modern, industrial materials and techniques. Among the most distinctive features of the building is the library, which features towering curvilinear woodwork in daringly dark timber.

For the interior furnishings, Mackintosh collaborated with his wife and fellow Glasgow School artist, Margaret Macdonald, who contributed to the unexpected combination of geometric and floral motifs throughout. They coordinated everything with the architectural features, from the curtains on the windows to the drinking glasses used in the building. The resulting building is multifaceted, audaciously asymmetrical, and full of personality—which is why “the Mack” was initially unpopular among Glaswegians. But its personality is what went on to make the Glasgow School of Art unquestionably emblematic of Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the soon-to-be-famous Glasgow School style. Tragically, the Mackintosh building was destroyed by fire in 2014 and is currently undergoing a painstaking restoration to its original state.

3. The Willow Tea Rooms

Turn-of-the-century Glasgow experienced an economic boom, so Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s burgeoning movement attracted a handful of wealthy Scottish patrons. One of these, eccentric entrepreneur Kate Cranston, took a chance on Mackintosh. A proponent of the increasingly popular temperance movement, her request was simple but very specific. Miss Cranston envisioned an immersive experience wherein Glaswegians could immerse themselves in all things Art Nouveau and enjoy a cup of tea. Mackintosh delivered the Willow Tea Rooms and helped start a thriving new trend in Scotland.

Thrilled by the total creative freedom granted by his patron—a rare indulgence for a professional architect, much less such a young one—Mackintosh transformed a four-story former warehouse into a modern masterpiece. He imbued the space with his distinctly Glaswegian interpretation of international Art Nouveau, going so far as to design the menus to match the architecture and furnishings. The Willow Tea Rooms, named for the decorative willow motifs interwoven throughout the total design, attracted crowds and inspired the inauguration of additional tea rooms across the city. Today, thanks to an extensive restoration, the Willow Tea Rooms remain open for business in Glasgow.

4. The Wooden High-Back Chair

Among Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s oeuvre of deceptively simple yet remarkably experimental designs is the high-back chair he originally created to go in the Willow Tea Rooms. He also made high-back chairs for his own home as well as many other designs, and it became synonymous with his name and that of the Glasgow School movement. In part thanks to Mackintosh’s repeated use of them in his total designs, high-back chairs became especially fashionable around the turn of the century. They integrated well into Art Nouveau spaces, which emphasize the aesthetic qualities of curvilinear lines and elongated forms. In the pictured high-back chair, the back legs are rectangular at the base and taper upwards into a round shape. This experimental use of form is exemplary of the Glasgow School style, which became famous—and controversial—for mismatching aesthetic inspirations and for rejecting the convention of symmetry.

5. Glasgow School Style Stained Glass

As an artistic medium, stained glass lent itself especially well to the Glasgow School movement. Ultra-stylized motifs, including the aforementioned Mackintosh rose, could transform when worked into a stained glass piece. Simple, distinct lines, flat planes of color, and vast swaths of negative space suddenly took on a more dynamic presence when formed with curved metal and colored glass—especially when light passed through the object. Charles Rennie Mackintosh and his fellow designers used stained glass extensively in their architectural commissions, embellishing doors and windows at every opportunity. Mackintosh was also keen to push the medium to its absolute limits, incorporating stained glass motifs into furniture, metalware, jewelry, and other small decorative objects.

6. The Hill House

On the outskirts of Glasgow, Charles Rennie Mackintosh built and furnished what is considered to be his domestic masterpiece: the Hill House. He designed the gray exterior to stand out against the rolling green landscape and blend in with the perpetually overcast skies of the Scottish countryside. The strikingly sparse color scheme is a mainstay of the entire home—though the visual interest throughout is anything but lacking. Mackintosh thought of everything and left nothing to chance, even leaving his patron with a precise type and color of floral arrangement that he should display on the living room table.

He collaborated with his wife, Margaret Macdonald, on the interior furnishings. She contributed delicate embroidery work and a gesso panel for the main bedroom, which showcases a delicate, feminine-inspired color scheme of white and pastel colors. In contrast, the dining room features dark, masculine-inspired woodwork and more angular linework. Despite its figurative staying power, the physical construction of Mackintosh’s Hill House has not fared well amidst the wet weather of the Scottish countryside over the years, making ongoing restoration a costly and difficult endeavor.

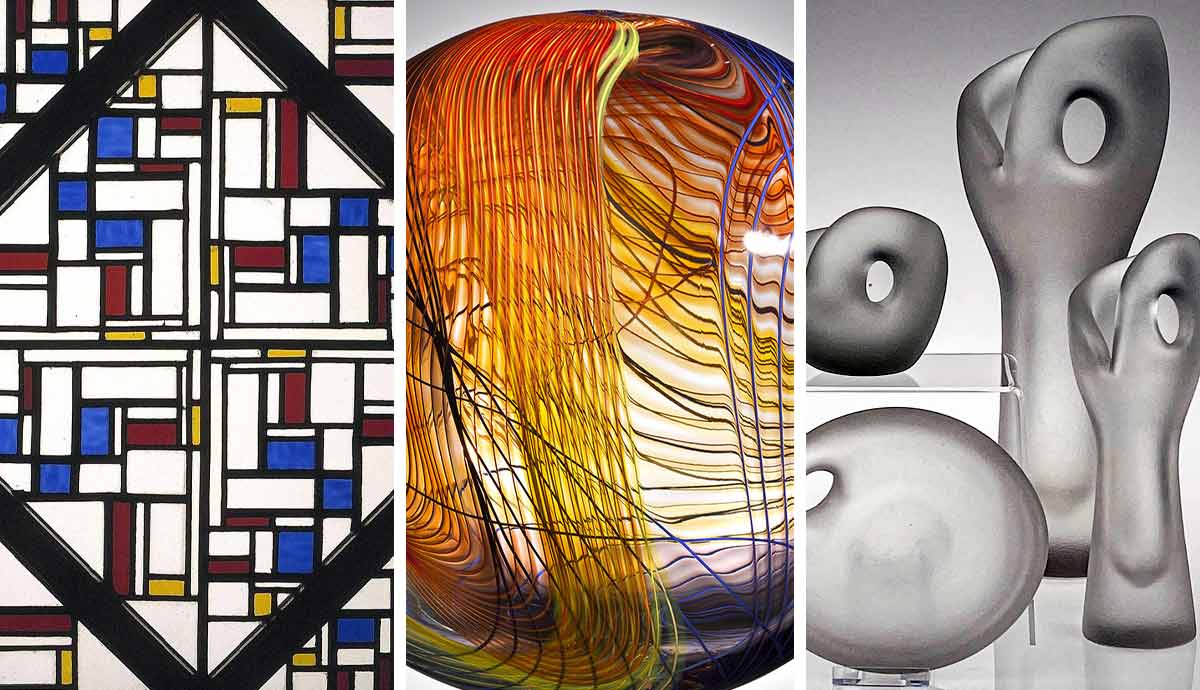

7. Textile Design Patterns

Textile design and production were already a mainstay of the Glasgow economy when Charles Rennie Mackintosh began drafting textile patterns. His interest in handcrafted techniques and medieval aesthetics was in part inspired by the British Arts and Crafts Movement, which had made its way up to Scotland from London. Mackintosh and other Glasgow School proponents viewed textiles as yet another vehicle by which to make their architectural designs a truly floor-to-ceiling experience. They designed patterns for furniture upholstery, wall coverings, embroidery pieces, and carpets. While not many original textiles have withstood the test of time, many sketches remain of the designs. True to the Glasgow School style, Mackintosh’s textile designs feature repeatable forms that are extremely stylized and typically elongated. The Mackintosh rose and other floral motifs make frequent appearances, but he also gravitated towards more abstract designs.

Many examples marry geometrical motifs, like checkerwork, with organic ones, like simplified flowers, to achieve an undulating, multilayered effect despite the flatness of the medium. Mackintosh’s textile designs were very commercially successful, especially when international Art Nouveau was at peak popularity. He was always able to rely on textile design as a source of income, even in his later years when the Glasgow School style became less marketable.

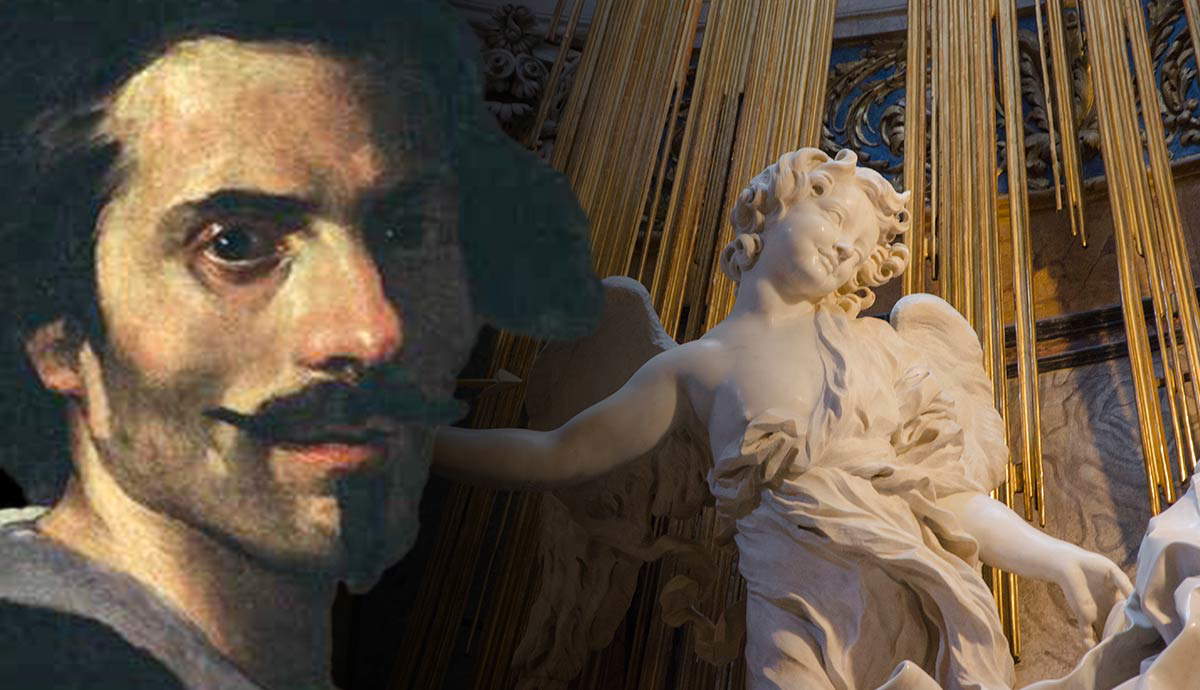

8. Scottish Art Nouveau Posters

The international Art Nouveau movement is still remembered for proliferating distinctive poster designs—and Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Glasgow School artists were no exception from the trend. New technology facilitated the mass production of printed materials, so illustrative work like posters and books became more popular and more lucrative for artists.

Likely inspired by English illustrator Aubrey Beardsley, designs like Mackintosh’s Glasgow School graphic designs are now remembered for being decidedly modern yet timeless. However, at the time of their creation, they received a lot of criticism for the simplicity and severity of their designs—especially the aesthetic distortion of the female form.

Nonetheless, Charles Rennie Mackintosh embraced posters and other illustrative, mass-producible design objects as another opportunity to push artistic boundaries. Typography became a vehicle by which to play with lines, and the printing press became a medium—much like stained glass—that allowed the artist to deconstruct creative concepts down to their simplest lines and color schemes.

9. 78 Derngate

Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s final major commission is also the only surviving example of his architectural work in England. Wealthy engineer W. J. Bassett-Lowke purchased a traditional early-19th-century terrace house in hopes that a total interior renovation by Mackintosh could launch the property into the modern era. Indeed, Mackintosh transformed every inch of the space into an Art Deco-inspired oasis—filled with dramatic dark woodwork, golden geometric designs, and eye-catching industrial light fixtures.

This was one of the first instances of Art Deco aesthetics being employed in English architecture. Bassett-Lowke was delighted with the result—as was the readership of Ideal Home magazine upon reading the series of feature articles about the transformation. The dazzlingly modern interior, juxtaposed with the unassuming, unmodernized exterior, emphasized Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s total design vision.

10. Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s Late Career Watercolors

As the 20th century marched on, Charles Rennie Mackintosh was frustrated to find that the Glasgow School style was falling out of fashion in Scotland and being replaced by newer Modern Art movements. Unwilling to compromise his aesthetic, Mackintosh abandoned much of his design work in favor of watercolor painting and left Scotland in hopes of feeling more appreciated in mainland Europe. He found some success as a freelance textile designer, but after his death, his work mostly faded into obscurity.

Although he was no longer creating the total designs he is now remembered for, the contrasting colors and flatness of this simple watercolor painting showcase what Mackintosh was ultimately famous for in his other mediums. Showcase his drawing prowess, careful observational skills, and knack for coloration, which he gained as a young student of drawing at the Glasgow School of Art.

Renewed interest in the work of Charles Rennie Mackintosh, fortunately, contributed to a revival, and in some cases extensive restoration, of his designs across Glasgow and in museums around the world. Indeed, Mackintosh’s art is the flower that makes Glasgow an exciting destination for any Art Nouveau aficionado—or even just the average tourist looking for a memorable place to have afternoon tea.