1968 was a tumultuous year in American political culture. Civil Rights advocates were growing frustrated with the lack of social progress despite the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965; the anti-war movement was vehemently protesting the ongoing Vietnam War, women were growing tired of continued institutionalized sexism, and the overall counterculture movement was thoroughly dissatisfied with the administration of US President Lyndon B. Johnson. After the tragic assassinations of both Martin Luther King, Jr. and US Senator Robert F. Kennedy (D-MA) earlier in the year, America was on a powder keg. At the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in July 1968, the powder keg erupted.

Setting the Stage: Civil Rights Dissatisfaction

In the mid-1960s, two landmark pieces of legislation were passed by Congress to improve the lives of minorities: the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which banned discrimination in public accommodations, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which banned literacy tests for voter registration and states’ attempts at race-based redistricting of legislative districts. The laws had a tremendous impact…but change was slower than expected. Although legalized segregation and voter restrictions had been banned, it was difficult to reduce personal prejudice held by individuals and privately owned businesses.

The Black Power movement, reinforced by groups like the Black Panthers and the Nation of Islam, is largely considered to have begun after the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. It featured a more aggressive call for cultural pride, economic self-determination, and armed self-defense for African Americans. Many Civil Rights advocates did not think desegregation was enough and began pushing for solutions to discrimination in housing, discrimination in employment, and overall economic inequality. Thus, beginning in 1966, the Civil Rights Movement took on a more aggressive stance and was tired of waiting for incremental improvements in the conditions faced by African Americans and other minorities.

Setting the Stage: The Anti-War Movement

The late 1960s saw a rapid growth of public opposition to the Vietnam War. As American casualties mounted in southeast Asia, critics called the conflict “unwinnable” and demanded that the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson bring the troops home. Instead, American involvement escalated up until the summer of 1968. The surprise Tet Offensive by North Vietnamese military forces and the Viet Cong communist guerrillas in South Vietnam in early 1968 shocked Americans who had been led to believe that the war was almost won. Not only was it clear that the communists in Vietnam were far from defeated, but it also appeared that the US government had been actively deceiving its own citizens about the state of the conflict.

Television news brought the horrors of the Vietnam War home to Americans in a way no previous conflict had been publicized. The same television news also brought increased public attention to the anti-war movement, intensifying feelings on both sides of the debate. Modern media also helped popularize the growing genre of anti-war protest music, with artists criticizing the government as both warmongering and hostile to marginalized communities. Both anti-war activists and those who supported the war effort courted media attention, hoping to win over the undecided. Thus, there was an incentive to be more active and passionate when television cameras were present.

March 1968: Johnson Decides Not to Run Again

The surprise Tet Offensive, combined with a growing anti-war movement, eroded Lyndon B. Johnson’s popularity. Members of the president’s own Democratic Party, especially US Senator Robert F. Kennedy (D-MA), publicly criticized the American involvement in the war immediately after the offensive. A month later, in the Democratic presidential primaries, Johnson found himself struggling mightily – a humiliation for an incumbent president. Then Robert F. Kennedy entered the race, raising the real possibility that Johnson might become the first elected president since before the American Civil War (1861-65) not to be nominated for re-election by his own party.

A few weeks later, Johnson announced on television that he would not be seeking re-election, a rarity in presidential politics. While Johnson explained his decision as a sacrifice so that he could focus all of his attention on leading the nation as chief executive, critics argued that the beleaguered president was trying to avoid a humiliating loss, either in the general election against Republican nominee Richard Nixon (bad) or in the Democratic primaries themselves (worse). However, Johnson’s announcement immediately boosted his popularity, especially as he seemed sincere in lamenting the political divisions among Americans and wanting to bridge them. It appeared that the president might be able to get more of his agenda passed through an impressed Congress.

April & June: Two Tragic Assassinations

Less than a week later, however, a tragic assassination diverted public attention from Johnson’s historic announcement. Civil Rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated by a rifle-wielding gunman while standing on his balcony at a hotel in Memphis, Tennessee on April 4, 1968. In the tragic aftermath of King’s death, riots erupted in Chicago, where King had lived, and many other cities. Although the emotionalism after King’s death may have been the spark that set the riots ablaze–literally–the riots were influenced by years of discrimination and economic inequality.

Two months later, a second liberal icon was assassinated. Senator Robert F. Kennedy, on the campaign trail during the Democratic presidential primaries, was shot and killed in a hotel kitchen. These two assassinations roiled the progressive wing of the Democratic Party and increased the overall feeling among the public that the country was in disarray. This increased dissatisfaction with national institutions, including social and religious ones, and their alleged ability to prevent violence and extremism. Many Americans felt hopeless and unsure about the country’s future success and stability.

Long Hot Summers (1965-68)

Summers have long been the season where crime increases. Heat tends to increase aggression, and longer summer days see many people spend more time outdoors in the late evenings. These summer evenings and outdoor socializing also increase alcohol consumption, which has a positive correlation with violent crime. The summers between 1965 and 1968 saw mass public unrest in urban areas, often racially motivated. These became known as the “long, hot summers” and often resulted in the National Guard being called in to quell urban rioting.

The “long, hot summer” of 1967 was incredibly intense and saw civil unrest in more than 150 cities. As a result, President Johnson commissioned the Kerner Commission – formally known as the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorder – to investigate the root causes of the violent unrest. The commission’s report determined that the unrest was due to long-simmering racial tensions underscored by high levels of unemployment and unpleasant interactions with law enforcement among young Black men. Most instances of unrest were sparked by alleged police brutality by white officers against Black men over seemingly minor infractions.

At the Convention: Massive Law Enforcement Presence

Against all of these backdrops, tensions were rising in Chicago, the host city of the 1968 Democratic Party National Convention. Police officers had grown increasingly tired of dealing with passionate political activists, and over time, more and more counterculture enthusiasts (i.e., “hippies”) had become seen by officers as political activists. After years of anti-war and Civil Rights protests, some of them violent, police officers were on edge during the summer of 1968. “Yippies,” or allegedly extremist members of the Youth International Party, allegedly increased tensions by making threats against Chicago infrastructure ahead of the Convention.

With Chicago mayor Richard J. Daley, a Democratic Party icon, worried about potential Yippie actions at the DNC, police officers were placed on twelve-hour duty rotations, and the Illinois National Guard was mobilized. Daley denied any permits to protest or march peacefully and imposed an 11:00 PM curfew. Despite efforts by protest leaders to organize and create plans to avoid hostile confrontations between protesters and law enforcement, the mayor refused to make any concessions and instead called up some 300 officers for a rapid-reaction riot task force. Over 1,500 officers were stationed at the site of the convention – a massive police presence!

At the Convention: Hubert Humphrey Chosen

In late April, after the end of the Democratic presidential primaries, Vice President Hubert Humphrey entered the race. Unlike his Democratic rivals, senators Eugene McCarthy and Robert F. Kennedy, Humphrey was not especially favored by young voters. He was also largely seen as Johnson’s administration replacement rather than a truly independent candidate. As a result, Humphrey attracted anti-war protests as his campaign began in May. On the campaign trail, he struggled to separate himself from Johnson’s unpopular escalation of the Vietnam War. He had to explain that the vice president essentially served the president as an advisor.

After Kennedy’s assassination in June, Humphrey seemed guaranteed the nomination following Eugene McCarthy’s suspension of his campaign. But McCarthy, an anti-war candidate, planned to attend the Democratic National Convention, perhaps emboldening those who planned to protest. Many Democrats were angry at Humphrey’s victory; he was seen as having been handed the nomination through backroom dealings by President Johnson. Having not run in the primaries, Humphrey was often seen as bypassing the democratic process. One goal of protesters arriving in Chicago was to convince delegates at the convention to shift their support to McCarthy.

The Chicago DNC Riots Begin

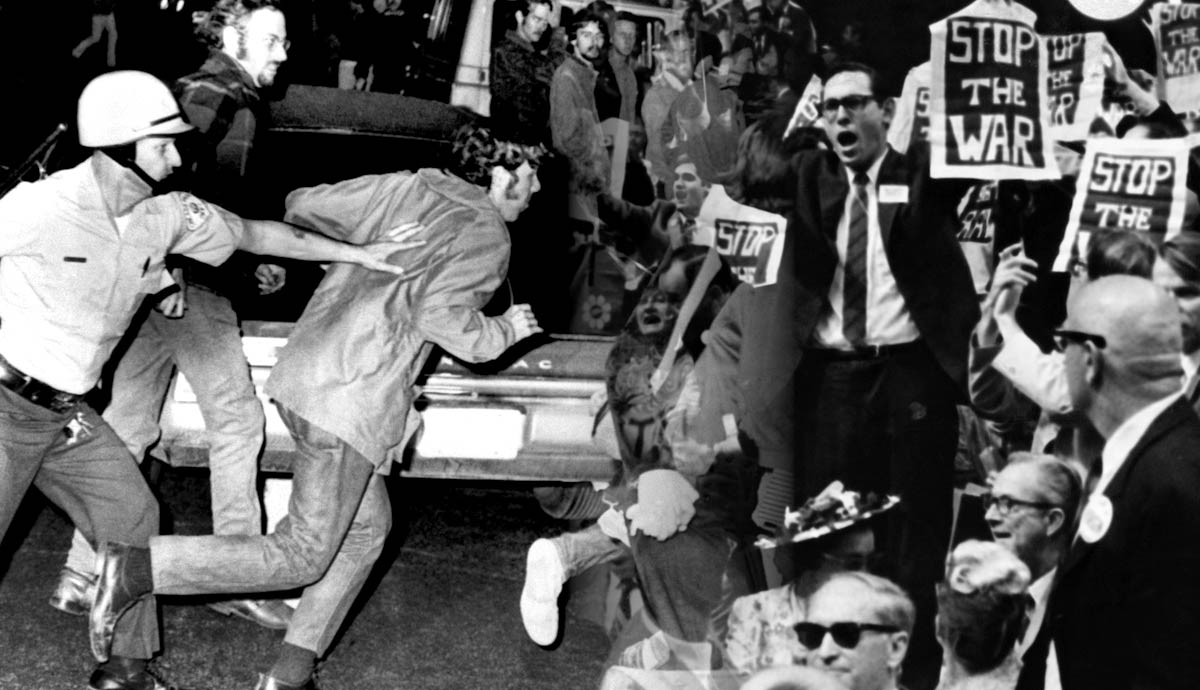

On Monday, August 26, 1968, delegates of the Democratic Party met in the International Amphitheater in Chicago. Demonstrations began outside on that first day but were not filmed. On the second day, tensions rose inside the convention as pro-Johnson delegates, who supported Vice President Hubert Humphrey, feuded with delegates who supported anti-war senator Eugene McCarthy. On the third day, August 28, protesters arrived in force at Grant Park after a televised debate the previous midnight over the Vietnam War. Although the protesters had a permit – granted at the last minute by a judge – to assemble in the park, protest organizer Rennie Davis was beaten by Chicago police officers. Around this point, the peaceful protest began to devolve into a riot, with violence committed by both police officers and protesters.

Many protesters wanted to leave the park and approach the Conrad Hilton Hotel, where many political dignitaries were staying during the convention. The hotel was surrounded by the Illinois National Guard, and approaching protesters were warned away with fixed bayonets. Fortunately, the crowd of protesters did not attempt to break the National Guard cordon, although individual protesters did tussle with police outside the hotel. Protesters also fought with police at Grant Park, with both sides accused of provoking the violence.

“The Whole World is Watching”

The evening of August 28 devolved into violence, with police and National Guard forces mobilized to disperse the crowd of protesters at Grant Park. Famously, protesters were heard chanting on national television, “the whole world is watching!” in reference to the media presence. Indeed, camera crews caught disturbing sights of police officers attacking protesters with mace and clubs, seemingly indiscriminately. Images of police using such strong force on unarmed protesters led many to call the events of that night a “police riot,” claiming that law enforcement was out of control.

The next morning, famed journalist Walter Cronkite interviewed Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley after the media received criticism of allegedly liberal coverage of the protests. At the time, the media was supposed to be unbiased, known as the Fairness Doctrine, and many viewers felt that the media had not covered the allegedly inflammatory actions of the protesters. In an attempt to show a balanced portrayal of the situation, Cronkite praised Daley and the police during his interview, which was considered the low point of the journalist’s career.

Aftermath of the Chicago Riots of 1968

Two changes occurred in the aftermath of the DNC Riots of 1968. The first was the role of the media. Until 1968, the media had tried to be an unbiased force in informing and educating Americans. Events in Vietnam and at the Democratic National Convention in Chicago made many journalists uncomfortable with the principle of trying to present “both sides” of controversial issues. After 1968, journalists felt they needed a freer hand to present the facts as they witnessed them rather than seeking evidence for both sides. Today, many consider this to be biased journalism (a cousin of the rampant yellow journalism of the late 1800s). Others, however, see this as the truth, with the media reporting facts rather than seeking “balance” that requires ignoring or defending wrongdoing by one side.

A more objective change was the creation of the modern presidential primary system. By 1976, the Democratic Party had settled on all delegates being awarded by candidates’ popular vote performance (relatively speaking) in presidential primaries and caucuses. Anti-war activists had seen Hubert Humphrey’s nomination in 1968 as a violation of democracy; his delegates had come from state conventions of party members. Today, both major political parties abide by the presidential primaries rather than the state convention system, with the presidential nominee chosen by the popular vote of those who voted in the primaries and caucuses.