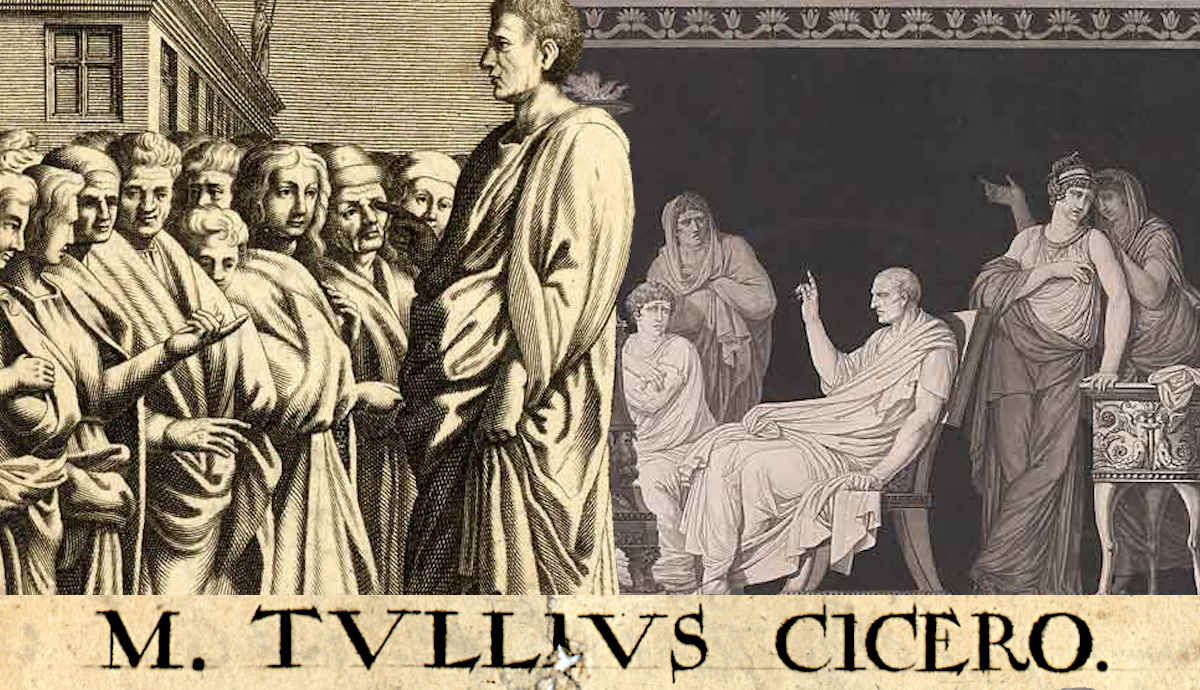

Born in 106 BCE in the town of Arpinum, over 100km from Rome, Cicero began his career as an outsider to the Roman political elite. Although the distinctions between classes in Rome had shifted by the late Republic, many prominent figures that dominated the political landscape still came from powerful and established patrician families. Instead, Cicero was a novus homo, or new man, the first in his family to enter the senate and later serve as consul. Cicero’s rising status in the capital began with his appearances in the city’s law courts, with his earliest published speech coming in 81 BCE at age 26.

Cicero’s most famous work as a lawyer came in 70 BCE in a case in which Cicero prosecuted Roman magistrate Gaius Verres. The charges related to allegations of corruption while Verres was the governor of Sicily. After Cicero had made his first speech, largely addressing Verres’ attempts to delay the trial, Verres left Rome in voluntary exile on the advice of his lawyer Hortensius. Cicero, in characteristic fashion, published his prosecution throughout the capital, including his second speech, which had not been heard in court. Cicero’s success in this trial helped build his reputation as one of Rome’s pre-eminent orators, an invaluable skill for a political career in the capital. Read below for more information on the speeches that defined Cicero’s political career as the pre-eminent orator of the late Roman Republic.

Cicero’s Early Speeches in Rome’s Law Courts

Cicero’s political career navigated a tumultuous period in Rome’s history, beginning during the Social War, a civil war between Rome and its Italian allies relating to citizens’ rights within the Republic. At the time of the war, Cicero was not old enough to take the initial office in the Cursus Honorum, the series of offices making up the early careers of aspiring politicians within Rome. Instead, Cicero began, reluctantly, gaining the military experience required for a political career in Rome, serving under Pompeius Strabo and Sulla.

1. Pro Quinctio

The first of Cicero’s published speeches in Rome’s law courts came in Pro Quinctio in 81 BCE when Cicero was 26. Repeated references to previous defenses throughout the speeches indicate some of Cicero’s previous experience as an advocate. The case was a private legal dispute over property between Publius Quinctius and Sextus Naevius. Navius was represented by Quintus Hortensius, a powerful orator, and former consul Lucius Marcius Philippus, a central figure in Sulla’s dictatorship. Cicero’s defense called Naevius’ character into question while establishing Quinctius as a sympathetic figure. The defence also highlighted the instability of the time, painting Quinctius as a victim of powerful figures in a corrupt, lawless society.

2. Pro Roscio Amerino

These same themes were central in Cicero’s next defense, Pro Roscio Amerino, in 80 BCE. In a controversial case, Cicero defended the younger Sextus Roscius from a charge of patricide against his father, the elder Sextus Roscius. Cicero’s speeches focused on a lack of evidence for the allegations, arguing that Sextus had neither the motive nor the means to commit the crime. Cicero shifted the focus, arguing that Sextus’ relatives, Titus Roscius Magnus, who was in Rome at the time of the murder, and Titus Roscius Capito, who was disputing ownership of the elder Sextus’ property, were more plausible suspects.

Cicero built on this defense by arguing that the allegations had been architected by Lucius Cornelius Chrysogonus. Chrysogonus had been placed in charge of Sulla’s proscriptions in 82 BCE. The proscription list allowed for state-sanctioned killings, with the property of those on the list sold by the state. Cicero argued that Chrysogons added the elder Sextus to the proscription list after learning of his murder and bid for his property when it was sold, purchasing it at a fraction of its value. This defense was built on allegations of corruption within Sulla’s regime, although Cicero was careful not to implicate Sulla directly.

Sextus Roscius was acquitted of the charges, and the case helped to build Cicero’s reputation as an orator. Public speaking was highly valued as a skill in Ancient Rome, and Cicero began to build his reputation as Rome’s pre-eminent orator through published speeches from Rome’s law courts. Similarly to Cicero’s later allegations against Catiline, modern scholars have questioned the voracity of Cicero’s allegations against Chrysogonos: the volume of Cicero’s extant texts means that in many of his early cases, we only have his perspective available.

There has also been speculation that some of the stronger allegations of corruption within Sulla’s regime were added to later publications of the speech and did not form part of the defense. It is clear that Cicero recognized the benefit of publishing speeches to build his reputation as an orator and, in many cases, may have edited these speeches to improve the arguments or paint his statements in a more favorable light. These questions remain relevant when reviewing speeches throughout his career. In the Catiline conspiracy, for example, some scholars have questioned whether Cicero’s allegations were exaggerated or even completely fictitious.

Cicero Against Verres

In 75 BCE, having been appointed as a quaestor, the most junior office in the cursus honorum, Cicero was assigned to the province of Western Sicily. While serving in the province, Cicero became aware of governor Gaius Verres’ corrupt practices. Verres gained Sulla’s favor when he switched allegiances in Sulla’s civil war. He retained his political influence after Sulla’s death in 78 BCE and served as governor of Sicily from 74 BCE to 70 BCE. During this time, he was accused of extorting locals, robbing temples, and imposing unaffordable taxes, among other charges.

On his return to Rome in 70 BCE, he was prosecuted by Cicero at the request of Sicilians who had suffered under Verres’ governance. Verres chose Hortensius to defend him in the trial. The pair worked to delay the prosecution until the following year when Metellus and Hortensius would take office as consuls and could influence the trial’s outcome. Cicero’s first speech addressed this cynical strategy directly, and Hortenius, declining to respond, advised Verres to leave Rome in voluntary exile. Despite this effective plea of no contest, the speeches from the trial, including those not heard in court, were compiled and published, outlining the cases against Verres.

One notable aspect of this case was Cicero’s approach to addressing the jury, made up exclusively of senators. This approach to jury composition was introduced by Sulla in 81 BCE. The rule was controversial as many felt it was unlikely a jury of senators would find another senator guilty. Cicero challenged this perception, directly characterizing the case as an opportunity for the jury of senators to prove that this approach could achieve a fair outcome. The law ‘Lex Aurelia judiciaria’, introduced in 70 BCE shortly after the Verres left Rome, stipulated that juries in political corruption trials would be made up of an equal proportion of senators, equites, and tribuni aerarii (although this term translates to tribunes of the treasury, by 70 BCE it appears to refer more broadly to a social class). The introduction of this law meant that Verres’ trial was the last to implement Sulla’s law on jury composition.

Cicero Denounces Catiline

Cicero’s success in this prosecution helped propel his political career, and he was elected consul only seven years later in 63 BCE. The defining moment of Cicero’s political career came during this consulship in a series of speeches addressed to the senate in which Cicero accused senator Catiline of a conspiracy against the Roman state. Catiline had stood for consul the year before but lost the election to Cicero. After a further defeat in the consular elections of 63 BCE, Catiline began forming a group of political malcontents building support after Rullus’ land reform bill was quashed partly due to Cicero’s resistance to the proposal.

With rumors spreading of Catiline’s conspiracy, the first hard evidence reached Cicero in late October. Marcus Licinius Crassus passed letters to Cicero containing details of the conspiracy’s plans for a coup d’etat killing key figures in Roman politics. The discovery of this conspiracy led the government to declare a state of emergency. The conspirators attempted to assassinate Cicero in early November, while further evidence against Catiline led to him being indicted. This formed the backdrop to Cicero’s most well-known speech on 7th November 63 BCE in the first of four speeches addressing the conspiracy. With Catiline present in the Senate, the speech opened:

“When, O Catiline, do you mean to cease abusing our patience? How long is that madness of yours still to mock us? When is there to be an end to that unbridled audacity of yours, swaggering about as it does now?”

The first oration was relatively short, at 3,400 words, likely around 30 minutes in length. Although Catiline protested the speech, challenging Cicero’s status as a new man, Catiline later left the city in a move he characterized as a voluntary exile.

In the second oration, this time addressed to the people of Rome, Cicero stated that, rather than leaving the city in exile, Cataline had left the city for Etruria to join his co-conspirators. The speech characterized Cataline’s conspirators as political malcontents, heavily indebted wealthy men and criminals. This was intended to establish that Catiline’s conspiracy was planned with selfish motives and not in the interests of the people of Rome. Several conspirators were arrested in Rome when members of a Gallic tribe acted as double agents, providing information to Cicero.

This led to a debate in the senate over the conspirators’ punishment. Cicero argued strongly for execution without trial, a position which was reflected in the speeches of the ex-consuls who spoke after him. Julius Caesar, a praetor in 63 BCE, argued against this course of action, instead advocating for life imprisonment. The senate was swayed by this argument. However, Cato the Younger argued for execution without trial and regained support for this course of action. The alleged conspirators were executed without trial, and Cataline was killed in a battle in which his forces were defeated by Cicero’s co-consul Gaius Antonius Hybrida.

The Legacy of the Catiline Conspiracy

The decision to execute the alleged conspirators without trial was controversial in the years following the conspiracy, with modern debates echoing similar themes around excesses of the state justified by national security arguments. These speeches were characteristic of Cicero’s complex legacy, leveraging powerful and persuasive oratory to achieve personal political goals in a time of instability. Cicero was exiled from Rome in 58 BCE for executing Roman citizens without a trial, although he would later return to the city. Clodius’ exile of Cicero has been interpreted by some as politically motivated, acting on behalf of the triumvirate to remove the political challenge that Cicero presented.

Modern scholars have also challenged the credibility of Cicero’s allegations against Catiline. Our understanding of the Catiline conspiracy is largely seen through the lens of speeches and writing published by Cicero. The conspiracy was preceded earlier in 63 BCE by a proposal to redistribute land resisted by Cicero. This contrasted with Catiline’s promises to forgive debts throughout Rome during an economic crisis. In this context, Catiline could be viewed as a revolutionary figure, with Cicero advocating for the establishment’s interests. Alternatively, Catiline may have been motivated by personal debts and political ambition. Differing interpretations of the charges are ultimately speculative, with few surviving texts providing an insight into alternative perspectives.

Cicero’s Influence on the Latin Language

A wide range of factors contributed to Cicero’s influence on the Latin language throughout the Roman Empire and later in Renaissance Europe. One of these factors is the volume of his published work throughout the final half-century of the Roman Republic. Classicist Stephen Harrison highlighted this, stating, “Latin literature in the period 90–40 BCE presents one feature that is unique in Classical, and perhaps even in the whole of Western literature… …more than 75 percent of that literature was written by a single man: Marcus Tullius Cicero.”

The variety of literature authored by Cicero contributes to its influence, with texts varying from published speeches defending the Roman Republic to letters describing his views on members of the Roman political elite. The tumultuous political landscape that defined the late Roman Republic is also significant in explaining the historical significance of these texts as Cicero resisted the transformation of the Republic into an Empire. Although his writing does not provide an unbiased or neutral account of this period, it does offer a compelling perspective of a critical statesman’s ambitions, anxieties, and attitudes to this period.

The later influence of Cicero throughout Europe began to take shape when Petrarch, a humanist scholar who contributed to sparking the 14th Century Renaissance in Italy, came across a collection of Cicero’s letters. Despite viewing Cicero as the best example of classical Latin writing, Petrarch combined his influence with many other Latin writers. Historian John Monfasani described the shift by the 15th Century in the humanist view stating, “they sought to model their Latin after Cicero’s” to the exclusion of other influences on the basis that “classical Latin was true Latin” and “Cicero represented the pinnacle of classical Latin prose.” One of Greco-Roman antiquity’s defining orators, Cicero has influenced Latin writers and public speaking more broadly, mirroring the approach he employed to scale the political ladder of the late Roman Republic.